MILLENNIUM REFERENDUM INITIATIVE

CITIZENS UNITED FOR UNITED SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA NOW

THE LAST CALL FROM THE HIGHEST AUTHORITY

THE UNTHINKABLE. THE IMPERATIVE. THE IRREVOCABLE

A successful Sub-Saharan Referendum on unity will spark an incredible awakening for Sub-Saharan Africans, unveiling the immense joy and freedom that await them. They will harness the extraordinary power within themselves and envision a vibrant future brimming with limitless possibilities. This epiphany will inspire them to realize that the journey toward complete independence, self-sustaining development, and a fulfilling life is firmly in their hands and lies within the heart of Sub-Saharan Africa, free from the burdens of external aid, debt, and influences.

UNITED WE THRIVE STRONGER AND INCREASE IN NATIONAL WEALTH. DIVIDED WE REMAIN POOR AND UNDER CONTROL.

“If We appear to seek the unattainable, it has been said, then let it be known that we do so to avoid the unimaginable.”

THE TIME FOR UNITY HAS ARRIVED

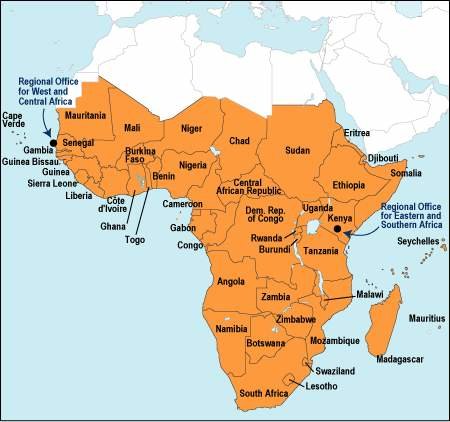

To the peoples of Sub-Saharan Africa:We are many nations, cultures, and languages—but we are one people. Together, we can forge a united future that lifts every Sub-Saharan African. Join us in this journey of transformation.

Imagine a Sub-Saharan Africa where borders are bridges, not barriers. A future where unity creates strength, and prosperity is shared by all. Together, we can build that Sub-Saharan Africa. Join the movement to make ‘One Sub-Saharan Africa, One Future’ a reality.

Sub-Saharan Africa’s destiny is in our hands. With one voice, we can shape a future defined by unity, progress, and complete independence. Join us today and be part of history.

From Cape Town to Lagos, from Addis Ababa to Central African Republic, Sub-Saharan Africa is alive with potential. But our greatest strength lies in what we can achieve together. Join us in this journey of fundamental change.

For decades, we have fought for freedom. Now, it’s time to fight for unity. Imagine a Sub-Saharan Africa where opportunities flow freely across borders, where shared resources fuel progress, and where every voice matters under a strong Union government of the people, for the people, and by the people of Sub-Saharan Africa. Yes, We Can Create that new Sub-Saharan Africa. In God We Must Trust!

Slogans

Unity and Action

- “One Sub-Saharan Africa, One Future.”

- “Together, We Rise.”

- “Unity in Diversity, Strength in Solidarity.”

- “Our Sub-Continent, Our Voice, Our Destiny.”

- “Building Sub-Saharan Africa’s Tomorrow, Today.”

Inspired by Progress

- “Unite for Prosperity, Lead for Change.”

- “A Stronger Sub-Saharan Africa Begins with Us.”

- “Dream. Unite. Transform.”

- “From Many Nations, One Future.”

- “For a New Era of Sub-Saharan African Greatness.”

A Future Worth Fighting For

- In the heart of Sub-Saharan Africa, we stand at a pivotal moment in history. Our nations, rich with diversity and untapped potential, face a critical question:

- can we build a stronger, united future for ourselves and the generations to come?

- It is time for citizens and leaders across the region to come together and call for a referendum on unity.

- A decision that will chart the course of our future, based on the shared values of peace, prosperity, and collective strength.

- Together, Sub-Saharan Africa can rise above historical challenges.

- Together, unleash its true potential, and secure a future of dignity, prosperity, complete independence, and collective self-reliance.

The Importance of the Referendum

The referendum on unity is more than a political process—it is a historic opportunity for the people of Sub-Saharan Africa to redefine their future. By uniting, the region can amplify its strengths, overcome challenges, and pave the way for lasting progress and shared prosperity.

A successful African Referendum will spark a profound awakening among Sub-Saharan Africans, enabling them to realize that joy and freedom are well within their reach; they will harness the immense power they possess; they will envision a future filled with endless possibilities; they will come to recognize that genuine independence, sustainable development, and an enhanced quality of life rely entirely on their own initiatives and the abundant resources of Sub-Saharan Africa rather than depending on external forces and aid.

Unity among our countries and their peoples has been a shared dream since before our independence. Nationalist leaders instilled the promise of unity to rally Sub-Saharan Africans in their struggle against colonialism, proving that it is this very unity that paved our path to freedom. Now is the moment for us to unite once more. Sub-Saharan Africans must come together urgently to confront both the historical legacies and the contemporary challenges we face, harnessing our vast potential to create a brighter future.

Question for consideration: If nationalist leaders instilled the promise of unity to rally Sub-Saharan Africans in their struggle against colonialism, but fail to achieve unity after achieving independence what will they have proven to the world, to Sub-sahran Africa and its posterity?

Imagine a Sub-Saharan Africa where borders unite instead of dividing us- a region where our shared strength fuels innovation, prosperity, and peace for all. The vision for unity is more than a dream; it is a call to action. Together, we can create a future where every voice matters, every opportunity is shared, and every nation thrives as part of a greater whole. This is our time to rise above challenges, embrace our common destiny, and build a United Sub-Saharan Africa. Joing us in shaping this vision, because unity starts with you. Let’s make history together!

A referendum on the unity of Sub-Saharan African states carries significant importance, as it represents a transformative step toward achieving collective goals, addressing shared challenges, and unlocking the region’s vast potential.

THE TRIUMPHANT CALL OF UNITED SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA

O sons and daughters of Sub-Saharan Africa, let us come together and celebrate the triumphs achieved for our liberation.

O sons and daughters of Sub-Saharan Africa, let us devote ourselves to rise up as one people to defend our liberty and unity and progress.

O sons and daughters of Sub-Saharan Africa, let us unite to transform Sub-Saharan Africa into a global powerhouse.

O sons and daughters of Sub-Saharan Africa, let us all unite and strive together to uphold our rights and champion the cause of freedom and progress.

O sons and daughters of Sub-Saharan Africa, let us commit ourselves to work side by side and gather strength in unity and peace.

O leaders of Sub-Saharan Africa, sons and daughters of Sub-Saharan Africa, let find courage to unite for common good and labor diligently to forge unity and offer our very best to Sub-Saharan Africa, our pride and hope.

O sons and daughters of Sub-Saharan Africa let embrace unity now and elevate Sub-Saharan Africa and make our beautiful Sub-Saharan Africa a rising sun powerhouse on global stage.

O sons and daughters of Sub-Saharan Africa let embrace unity now and achieve our long-held collective aspiration for the United Sub-Saharan Africa.

SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA ANALYSIS

Population Dynamics and Access to Services

Total population and access to basic services

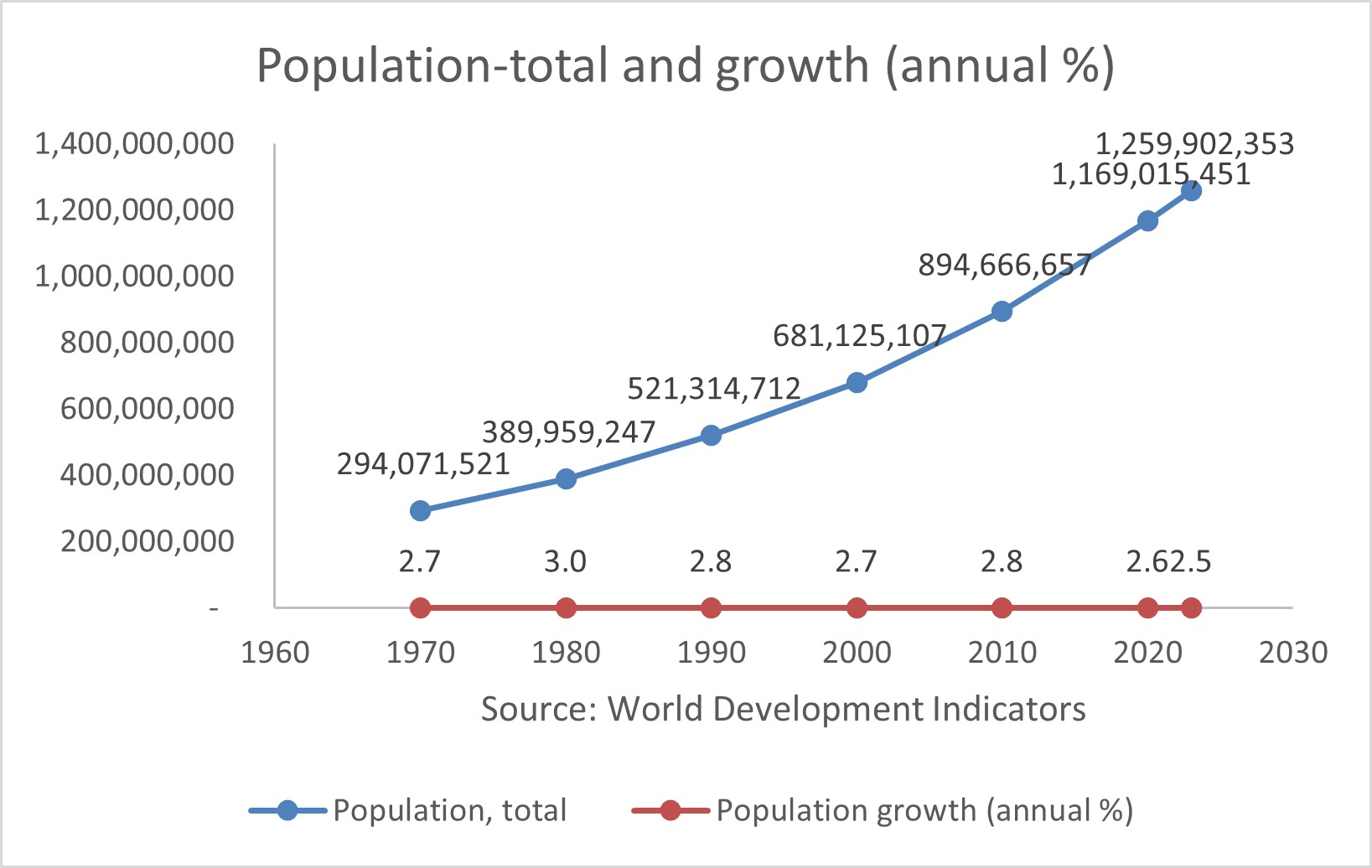

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is experiencing significant demographic changes characterized by a growing total population, shifts between rural and urban living, and the implications of these trends on economic development. As of 2023, the total population in Sub-Saharan Africa is estimated to be over 1.2 billion people, with projections indicating continued growth in the coming decades. This rapid population increase is primarily driven by high birth rates

Access to electricity

In 2020, just 49 percent of Sub-Saharan Africa’s population had access to electricity, highlighting a significant energy gap compared to 97 percent in East Asia and the Pacific and 96 percent in South Asia. Globally 91 percent of the global rural population had electricity access that year.

Access to basic drinking water services

In 2020 only 63 percent of the population in Sub-Saharan Africa had access to basic drinking water services compared to 95.2 percent in East Asia and the Pacific and 92.1 percent in South Asia.Globally 90 percent of people enjoy access to essential drinking water services.

Access to Basic Sanitation services

In 2020, only 34 percent of the Sub-Saharan Africa population had access to basic sanitation, compared to 92 percent in East Asia and the Pacific and 70 percent in South Asia. Globally, 78 percent of the global population benefited from basic sanitation, while many in Sub-Saharan Africa remained without these essential services, underscoring the urgent need for collective efforts to improve access for all.

Rural population and access to basic services

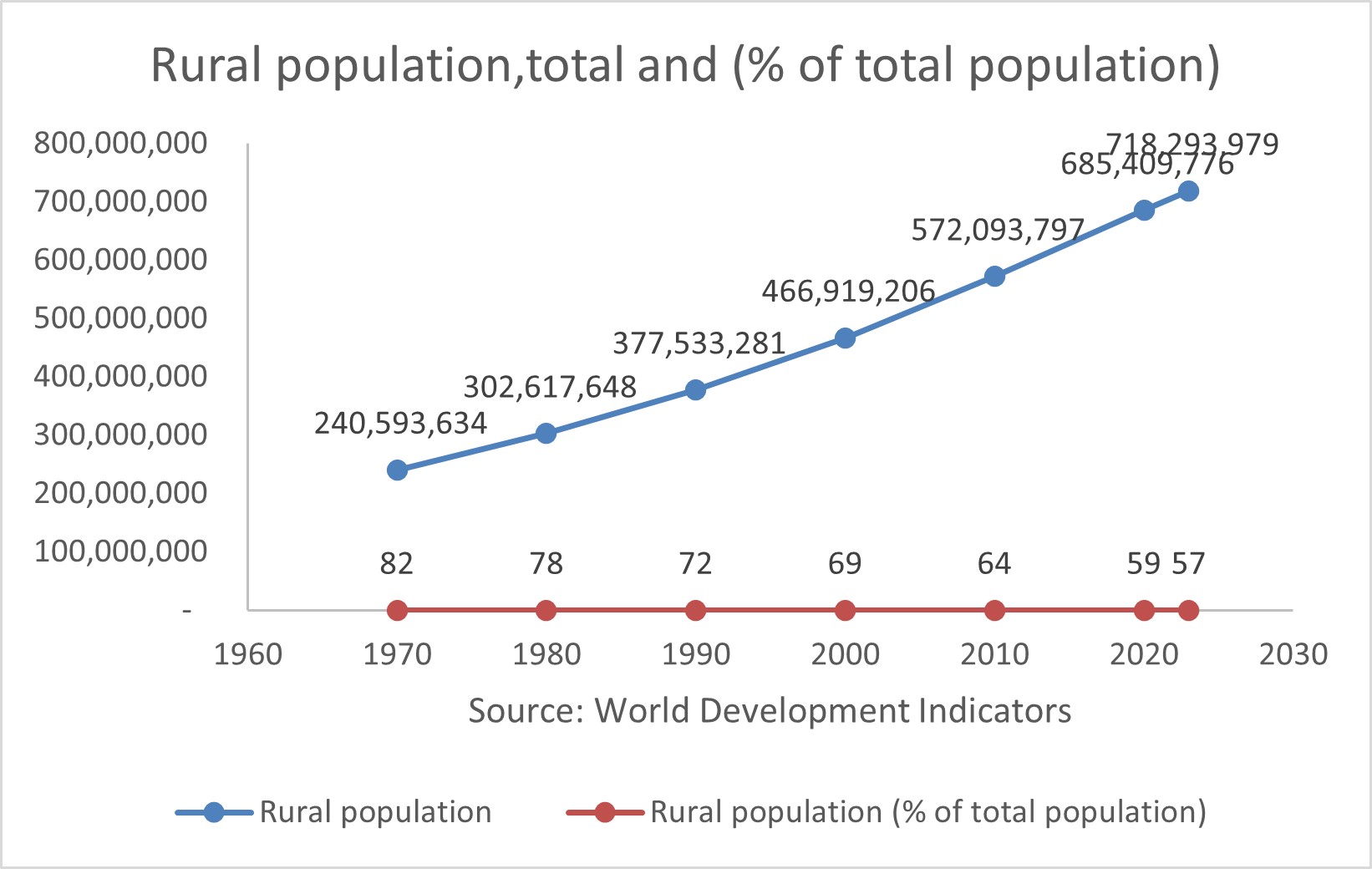

in Sub-Saharan The rural population in Sub-Saharan Africa has shown a gradual increase over recent years. In 2023, the rural population was approximately 718 million, reflecting an absolute change of approximately 33 million increases from the previous year. This trend indicates that while urbanization is accelerating, a substantial portion of the population continues to reside in rural areas.This data illustrates that although there is an ongoing trend toward urbanization, many individuals still depend on agriculture and other rural livelihoods.

Access to electricity

In 2020, only 29% of the rural population in Sub-Saharan Africa had access to electricity, which is a stark contrast to the 96% in East Asia and the Pacific and 95% in South Asia. While 83% of the rural population worldwide enjoys reliable electricity.

Access to basic drinking water services

In 2020, only 49 percent of the rural population in Sub-Saharan Africa had access to essential drinking water services, in stark contrast to 90 percent in East Asia and 90.3 percent in South Asia. 82 percent of the global rural population accessed to basic drinking water during the same period, underlining the critical need for unified efforts to achieve universal access to this vital resource in rural Sub-Saharan Africa.

Access to basic sanitation services

In 2020, it was disheartening to see that only 24% of the rural population in Sub-Saharan Africa had access to basic sanitation services, starkly contrasting with the 85% and 66% in East Asia and the Pacific and South Asia, respectively. During the same period, 66% of the global rural population enjoyed basic sanitation. These disparities underscore the urgent need for compassion and action to aid those lacking these essential resources in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Urban population and access to basic services

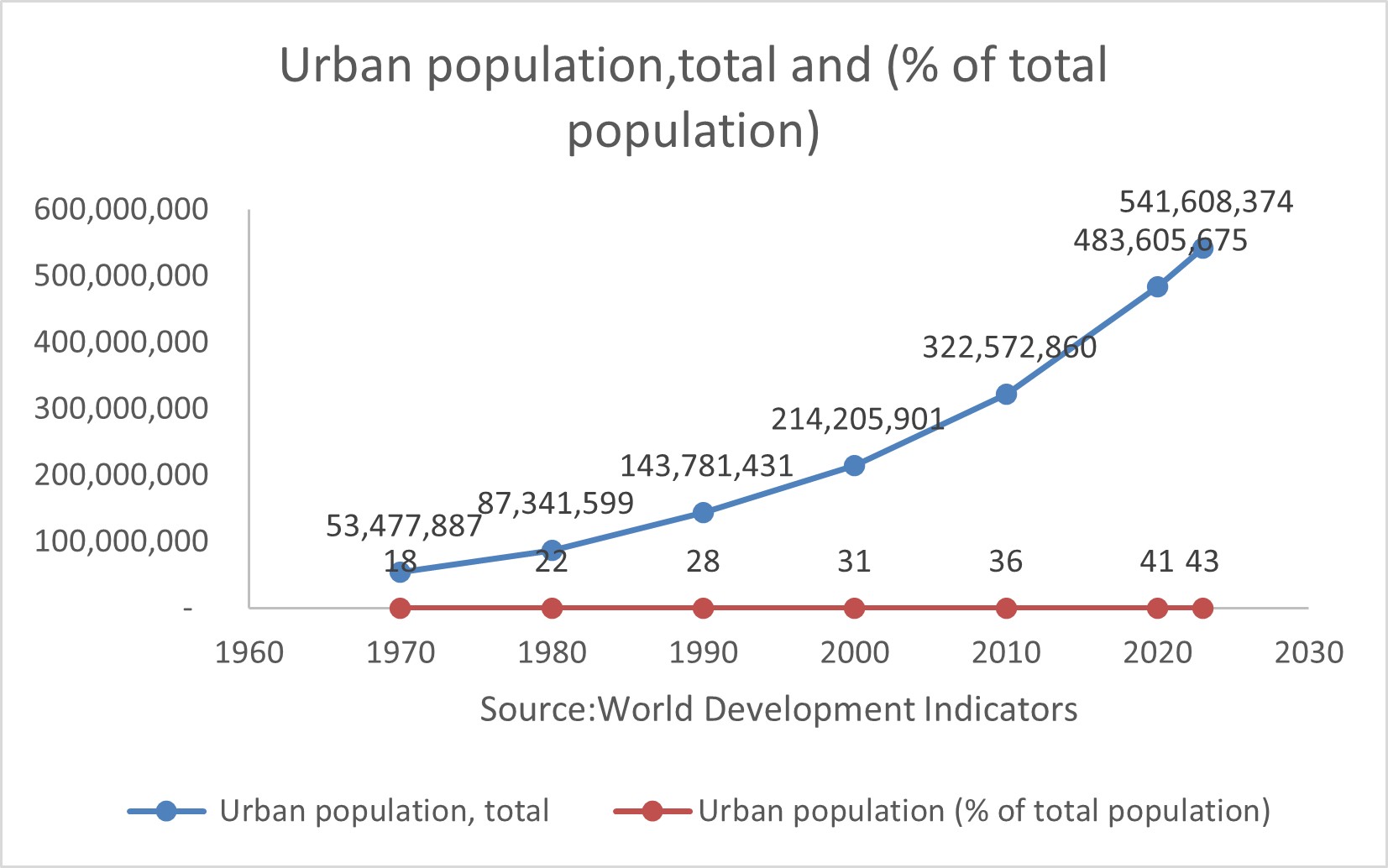

Conversely, urban areas in Sub-Saharan Africa are expanding rapidly. As of 2023, urban centers accommodate around 472 million people, with projections suggesting this number could double within the next 25 years due to an annual urban growth rate of approximately 4.1%, significantly higher than the global average of 2.0%. This shift towards urban living is driven by several factors, including economic opportunities and access to services. As urbanization progresses, it is projected that by 2050 more people will live in urban settings than in rural ones across Africa for the first time.

Acces to electricity

In 2020, only 78% of urban residents in Sub-Saharan Africa had access to electricity, trailing behind the 97% in East Asia and the Pacific and 99% in South Asia. Interestingly, in that same year, a striking 97% of the global urban population had electricity access.

Access to basic drinking water services

In 2020, 84 percent of the urban population in Sub-Saharan Africa had access to basic drinking water, compared to 98 percent in East Asia and the Pacific and 92 percent in South Asia, while in 2020, a remarkable 96 percent of the global urban population benefited from essential drinking water services.

Access to basic sanitation services

In 2020, just 48 percent of the urban population in Sub-Saharan Africa had access to basic sanitation services, starkly contrasting with 85 percent in East Asia and the Pacific and 78 percent in South Asia. This gap reveals a significant concern, especially given that 87 percent of the global urban population had basic sanitation access in 2020, emphasizing the critical need for advancements in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Health and Wellness Outcomes

Life expectancy in Sub-Saharan Africa

Under-5 mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa

Maternal morality in Sub-Saharan Africa

Fragmentation of the Sub-Saharan African Economy

Countries with Under 10 Million Inhabitants (20),2023

Table 1 below shows that in 2023, 20 Sub-Saharan African countries had a total population of approximately 64 million people according to the World Bank, while Tanzania’s population was around 67 million. In the same year, these 20 countries collectively had a GDP of less than 145 billion dollars, compared to Ethiopia, which had a GDP of 164 billion dollars. These 20 countries represent 5 percent of Sub-Saharan Africa’s overall population and 7 percent of the region’s GDP (World Development Indicators -2025).

Table 1. Country

GNI per capita, Atlas method(currentUS$)

Number in poverty ($2.15 a day)

Seychelles

Sao Tome and Principe

Cabo Verde

Comoros

Eswatini

Mauritius

Equatorial Guinea

Guinea-Bissau

Lesotho

Botswana

Gabon

Gambia, The

Namibia

Eritrea

Mauritania

Central African Republic

Liberia

Congo, Rep.

Sierra Leone

Togo

1,000

Total

64,239,259

Population,share of SSA(%): 5

$144,180,900,395

GDP, share of SSA(%):7

Sub-Saharan Africa

1,259,902,353

$2,044,578,421,950

Countries Under 30 Million Inhabitants (15),2023

In 2023, as indicated in Table 2, 15 Sub-Saharan African countries had a combined population of approximately 283 million people according to the World Bank, while Nigeria alone had around 228 million people. In 2023, the collective GDP of these 15 countries was under 300 billion dollars, contrasting sharply with South Africa’s GDP of 381 billion dollars. Together, these 15 nations comprised 14 percent of Sub-Saharan Africa’s total population and contributed 22 percent to the region’s GDP (World Development Indicators -2025).

Table 2. Country

GNI per capita, Atlas method(currentUS$)

South Sudan

Burundi

Rwanda

Benin

Guinea

Zimbabwe

Senegal

Somalia

Chad

Zambia

Malawi

Burkina Faso

Mali

Niger

Cameroon

Total

282,895,775

Population,share of SSA(%): 22

$296,188,032,777

GDP, share of

SSA (%):14

Sub-Saharan Africa

1,259,902,353

$2,044,578,421,950

Countries with More Than 30 Million Residents(13), 2023

In 2023, around 913 million individuals lived in 13 Sub-Saharan African countries, as reported by the World Bank, with Congo, Dem Rep., Ethiopia, and Nigeria representing nearly 51 percent of this population. These nations together produced a GDP of approximately 1.6 trillion dollars, contributing significantly to the total Sub-Saharan African GDP of 2 trillion dollars. Importantly, these 13 countries accounted for 72 percent of the region’s total population and generated 78 percent of its GDP (World Development Indicators – 2025).

Table 3. Country

GNI per capita, Atlas method (current US$)

Madagascar

Mozambique

Ghana

Angola

Uganda

Sudan

Kenya

South Africa

Tanzania

Congo, Dem. Rep

Cote d'Ivoire

Ethiopia

163,697,927,594

Nigeria

363,846,332,835

Total

912,767,319

Population, share of

SSA (%):72

$1,596,577,145,691

GDP, share of

SSA (%): 78

Sub-Saharan Africa

1,259,902,353

$ 2,044,578,421,950

State of Sub-Saharan Africa Sixty Years Post-Independence : A Global Perspective

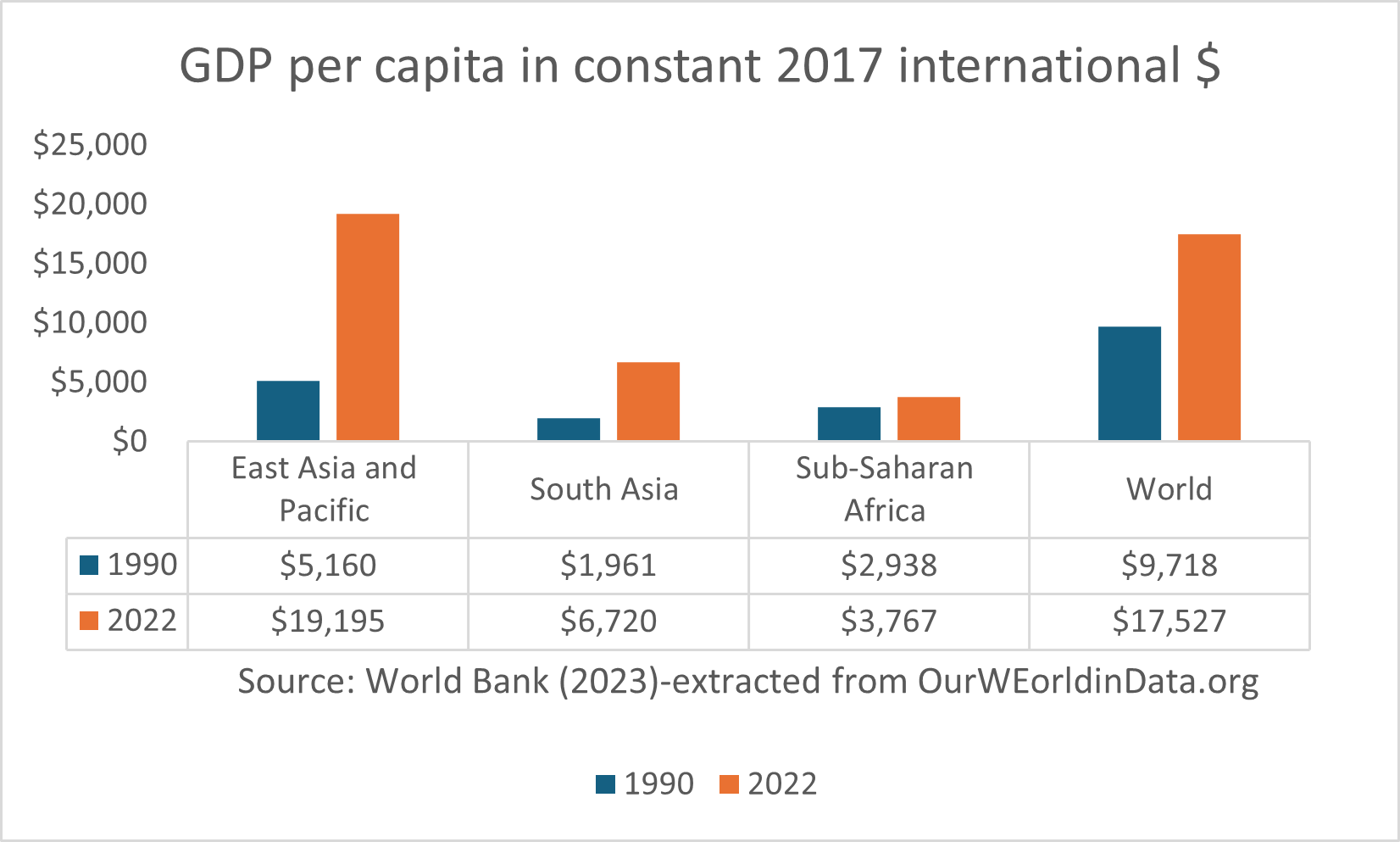

Lowest income per capita in the world, 2022

GDP per capita in Sub-Saharan Africa rose from $2,938 in 1990 to $3,767 in 2022, an increase of $829 . In East Asia and the Pacific, per capita income grew from $5,160 in 1990 to $19,195 dollars in 2022, a substantial rise of $14,305. South Asia saw its per capita income change from $1,961 in 1990 to $6,720 in 2022, an increase of $4,759 . Globally, per capita income went from $9,718 in 1990 to $17,527 dollars in 2022, an increase of $7,809, highlighting that Sub-Saharan Africa is the only developing region where income has hardly changed despite the overall global wealth increase over the last few decades, Why?

In a world where technological advancements have propelled global wealth to new heights over the past 50 years, it is deeply concerning that Sub-Saharan Africa stands as the only developing region grappling with stagnation in per capita income, a reality that feels particularly disheartening given the region’s rich natural and human resources, especially in light of the optimistic forecasts made in the 1960s that envisioned it flourishing beyond its Asian counterparts with fewer natural endowments.

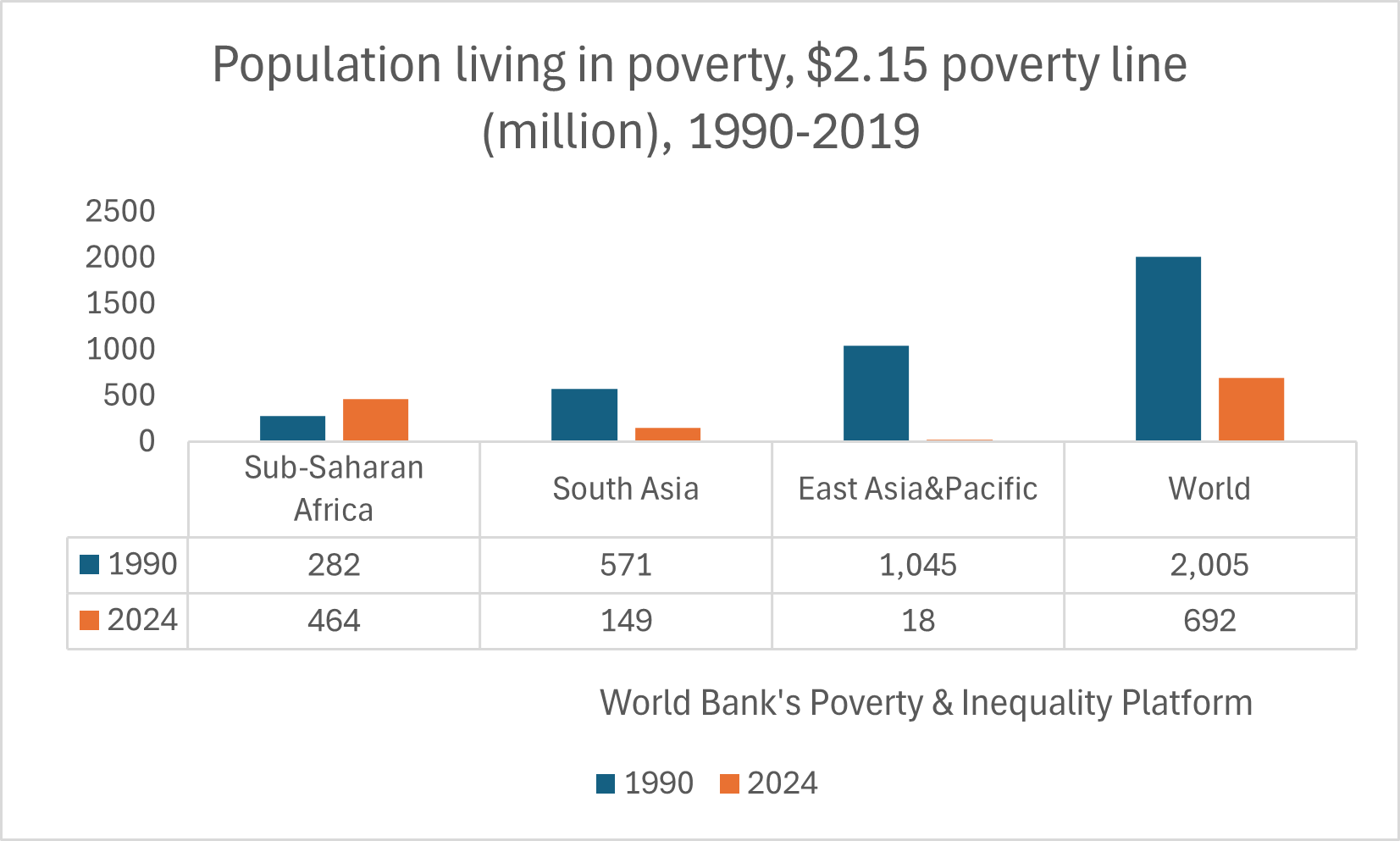

Highest number of people living in extreme poverty, 2024

The share of the population living in extreme poverty, defined as living on less than 2.15 dollars a day, has exhibited significant variation across different regions and globally. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the poverty rate has decreased from 54.6 percent in 1990 to 34.5 percent in 2024; however, the number of individuals in extreme poverty rose from 282.2 million to 464.2 million during this period. Conversely, East Asia and the Pacific saw a dramatic reduction in their poverty rate, which plummeted from 65 percent in 1990 to just 0.82 percent in 2024, resulting in a decline in extreme poverty from 1.04 billion to 17.6 million. Additionally, South Asia made notable progress, reducing its poverty rate from 50 percent in 1990 to 7.6 percent in 2024, while the number of individuals living in extreme poverty decreased from 570.9 million to 148.7 million. On a global scale, the overall poverty rate fell from 37.9 percent in 1990 to 8.6 percent in 2024, with the population in extreme poverty declining from 2 billion to 693 million, yet Sub-Saharan Africa remains the only developing region where extreme poverty has continued to increase since 1990.

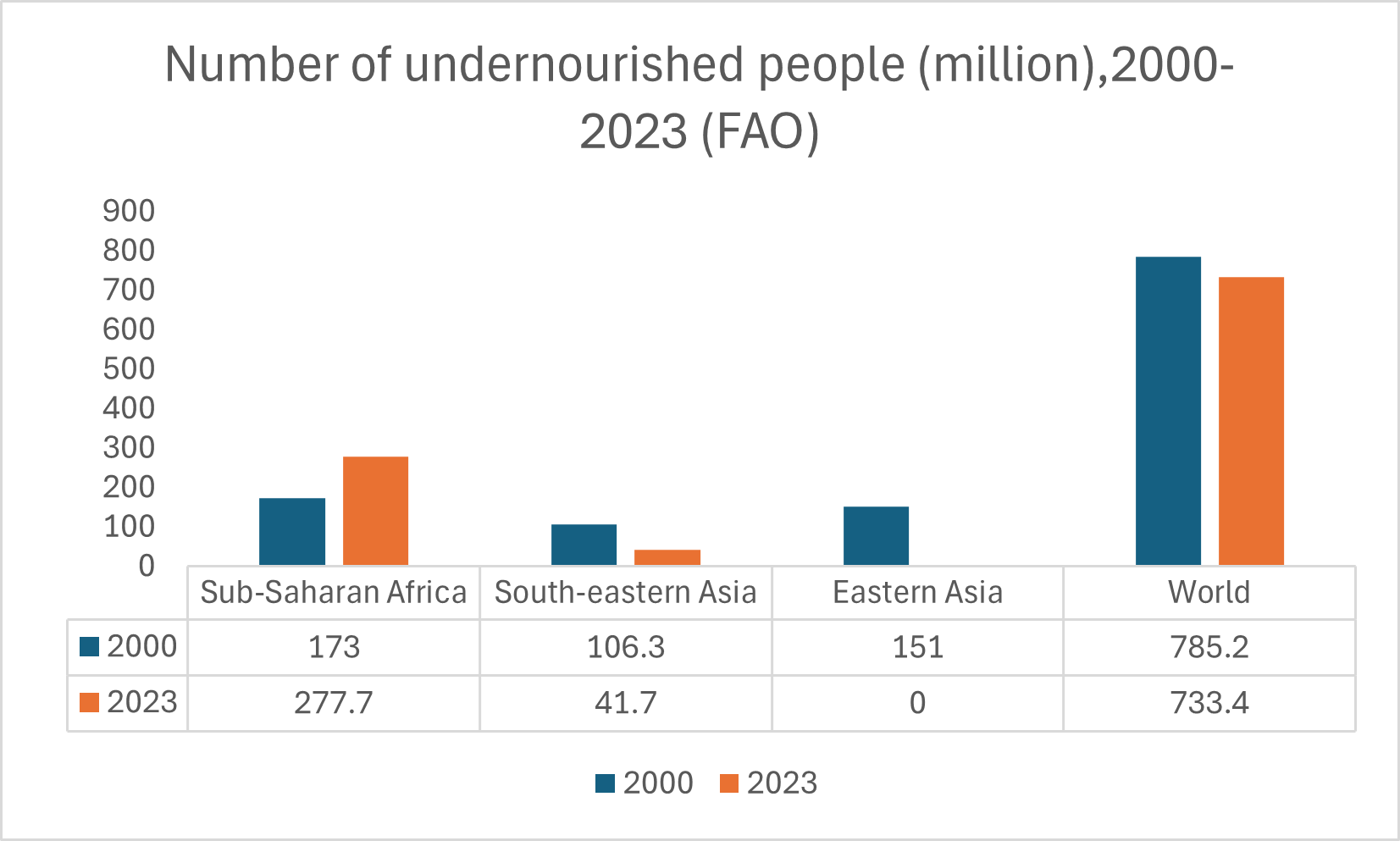

Highest number of hungry people, 2023

The number of undernourished individuals in Sub-Saharan Africa has alarmingly surged from 173 million in the year 2000 to a staggering 277.7 million in 2023, underscoring a critical and urgent issue within the region that demands immediate attention. In stark contrast, Eastern Asia has made remarkable strides in reducing undernourishment, witnessing a dramatic decline from 151 million in 2000 to an impressive zero in 2023. Similarly, Southeastern Asia has achieved significant progress, with the number of undernourished individuals dropping from 106.3 million to 41.7 million during the same period. On a global scale, the overall number of undernourished people has decreased from 785 million in 2000 to 733.4 million in 2023, reflecting positive advancements in various areas. However, it is particularly concerning that Sub-Saharan Africa stands out as the only developing region where the number of undernourished individuals continues to rise, especially given that it possesses the largest arable land area in the world, which raises questions about the effectiveness of governance practices and resource management in addressing hunger.

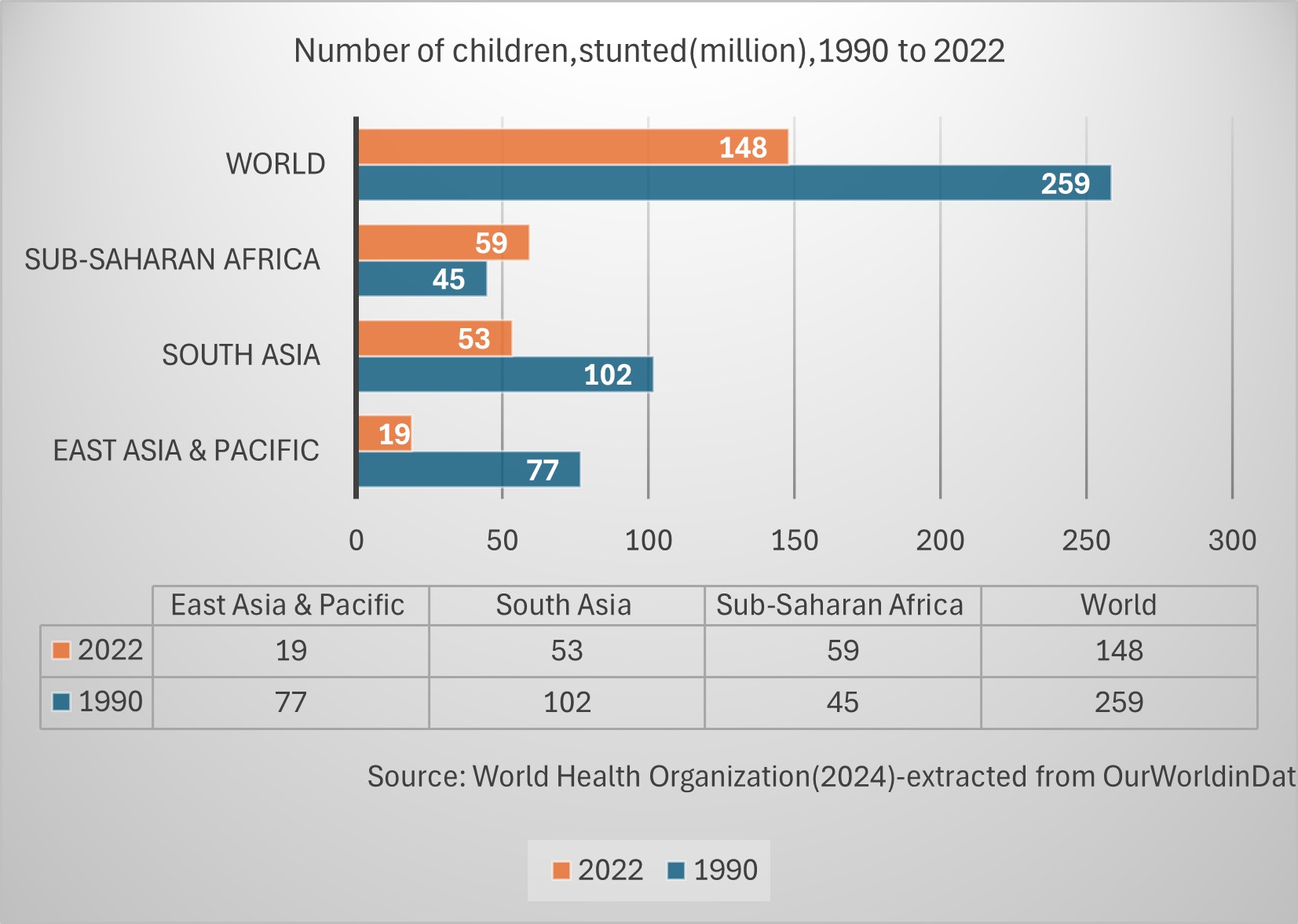

Highest number of stunted children, 2022

The number of stunted children under five reflects significant growth issues due to poor nutrition or frequent infections. In Sub-Saharan Africa, this number rose from 44.8 million in 1990 to 59.3 million in 2022, an increase of 14.5 million or 32%. Conversely, in East Asia and the Pacific, the count fell dramatically from 76.9 million to 18.9 million, a decrease of 58 million or 75%. Similarly, South Asia saw a decline from 101.8 million to 53.4 million, down by 48.4 million or 48%. Globally, stunted children decreased from 258.6 million in 1990 to 148.1 million, a reduction of 110.4 million or 43%, making Sub-Saharan Africa the only region where child malnutrition continues to rise,Why?

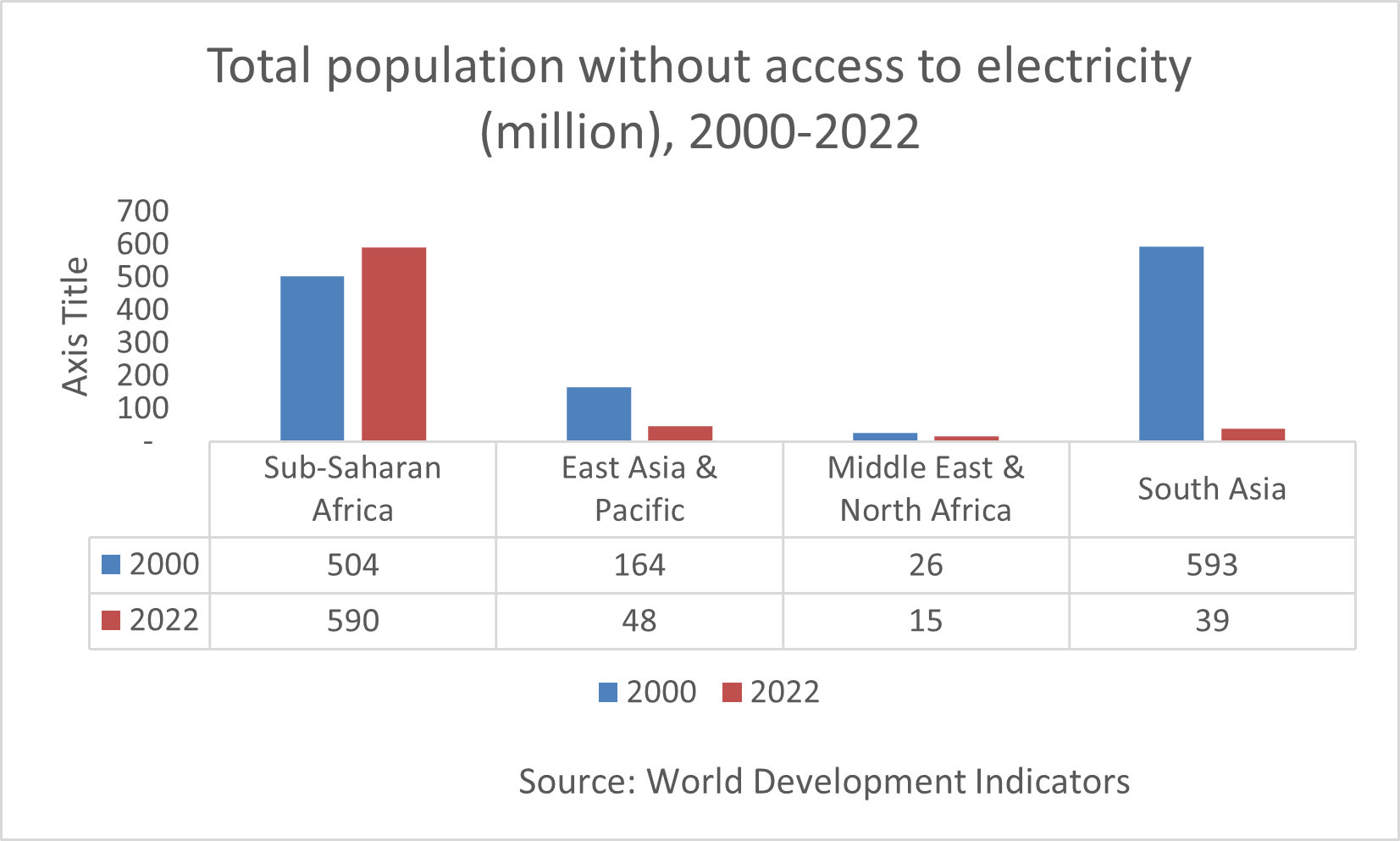

Highest total population without access to electricity (million),2000-2022

Between the years 2000 and 2022, the number of individuals in Sub-Saharan Africa who lack access to electricity saw a troubling increase, rising from 504 million to 590 million. This stark reality is in sharp contrast to the significant progress made in both East Asia and the Pacific and South Asia, where the number of people without electricity dramatically decreased from 164 million to 48 million and from 593 million to 39 million, respectively. This growing disparity is not just a statistic; it highlights the urgent need for comprehensive initiatives and innovative strategies in Sub-Saharan Africa to effectively tackle this critical issue and ensure that millions of people can achieve reliable access to electricity, which is essential for improving their quality of life and fostering economic development.

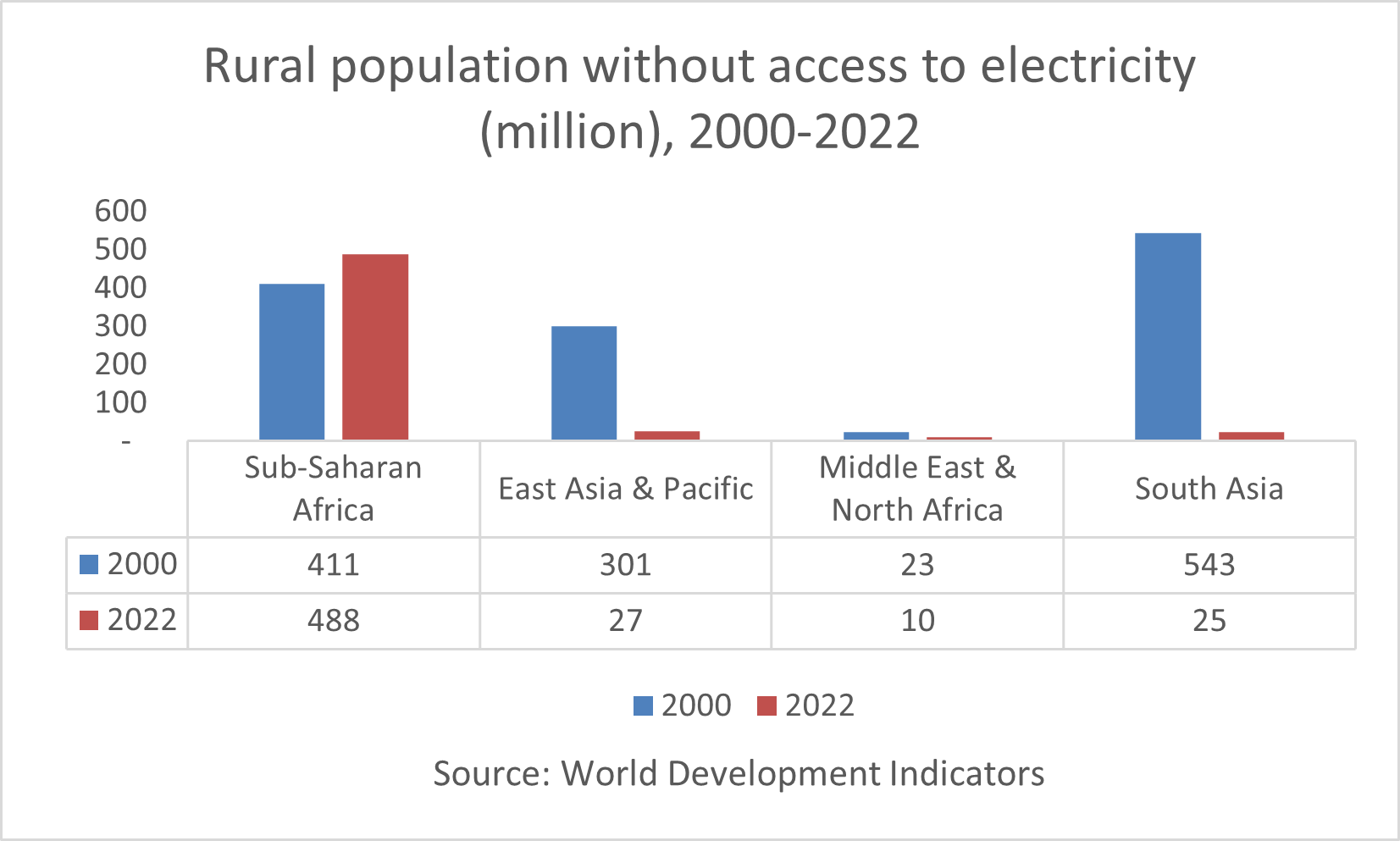

Highest rural population without access to electricity (million), 2000-2022

Between 2000 and 2022, the population without access to electricity in rural Sub-Saharan Africa surged from 411 million to 488 million, illustrating a profound and persistent challenge for the region’s development and economic growth. In stark contrast, East Asia and the Pacific, along with South Asia, achieved remarkable advancements, with the number of rural residents lacking electricity decreasing dramatically from 301 million to 27 million and from 543 million to just 25 million, respectively. This alarming trend not only highlights the disparity in energy access but also underscores the urgent necessity for innovative strategies and comprehensive solutions aimed at bridging the energy access gap in Sub-Saharan Africa, which is essential for enhancing quality of life and fostering sustainable development.

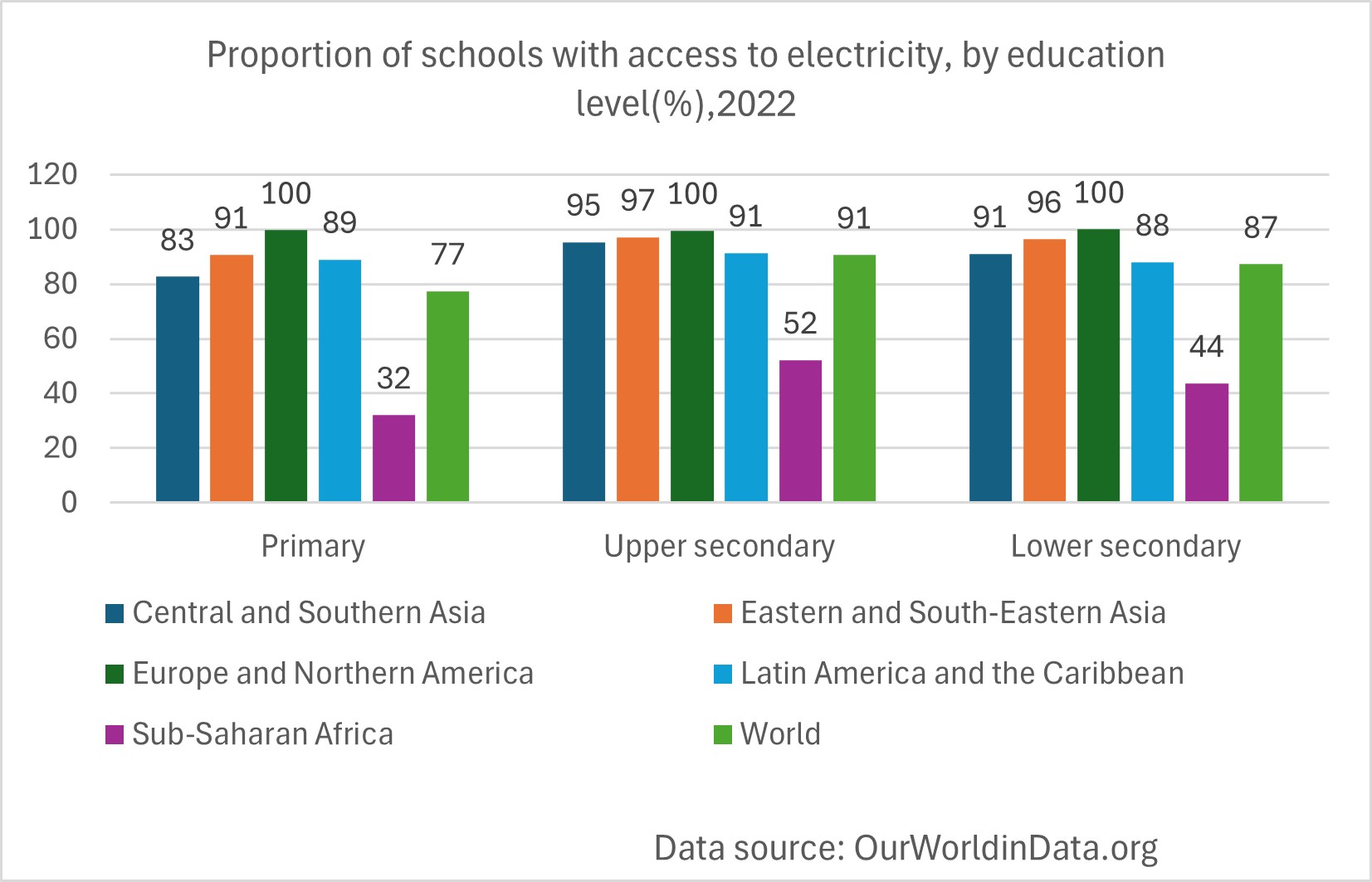

Lowest access to electricity in Primary, Upper Secondary and Lower Secondary schools in the world, 2015-2022

The situation in Sub-Saharan Africa regarding access to electricity in schools is deeply concerning, as evidenced by a decline in access for primary schools from 32.15 percent in 2015 to just 32.07 percent in 2022. Upper secondary schools have seen a similar decrease, dropping from 57.03 percent to 52.2 percent, while lower secondary schools have fallen from 47.65 percent to 43.7 percent within the same period. In striking contrast, Eastern and South-Eastern Asia have made remarkable progress, with primary school access climbing from 86.08 percent in 2011 to 90.62 percent in 2022, upper secondary schools rising ever so slightly from 96.98 percent to 97.13 percent, and lower secondary schools experiencing a significant improvement from 92.41 percent to 96.4 percent. On a global scale, the trends are similarly encouraging; access to primary schools surged from 65.01 percent in 2011 to an impressive 77.44 percent in 2022, upper secondary schools increased from 87.68 percent to 90.6 percent, and lower secondary schools advanced from 77.44 percent to 87.17 percent. It is deeply troubling that children in Sub-Saharan Africa continue to be among the few in developing regions deprived of this essential resource, raising urgent questions about the commitment to equity and the prioritization of education in the region.

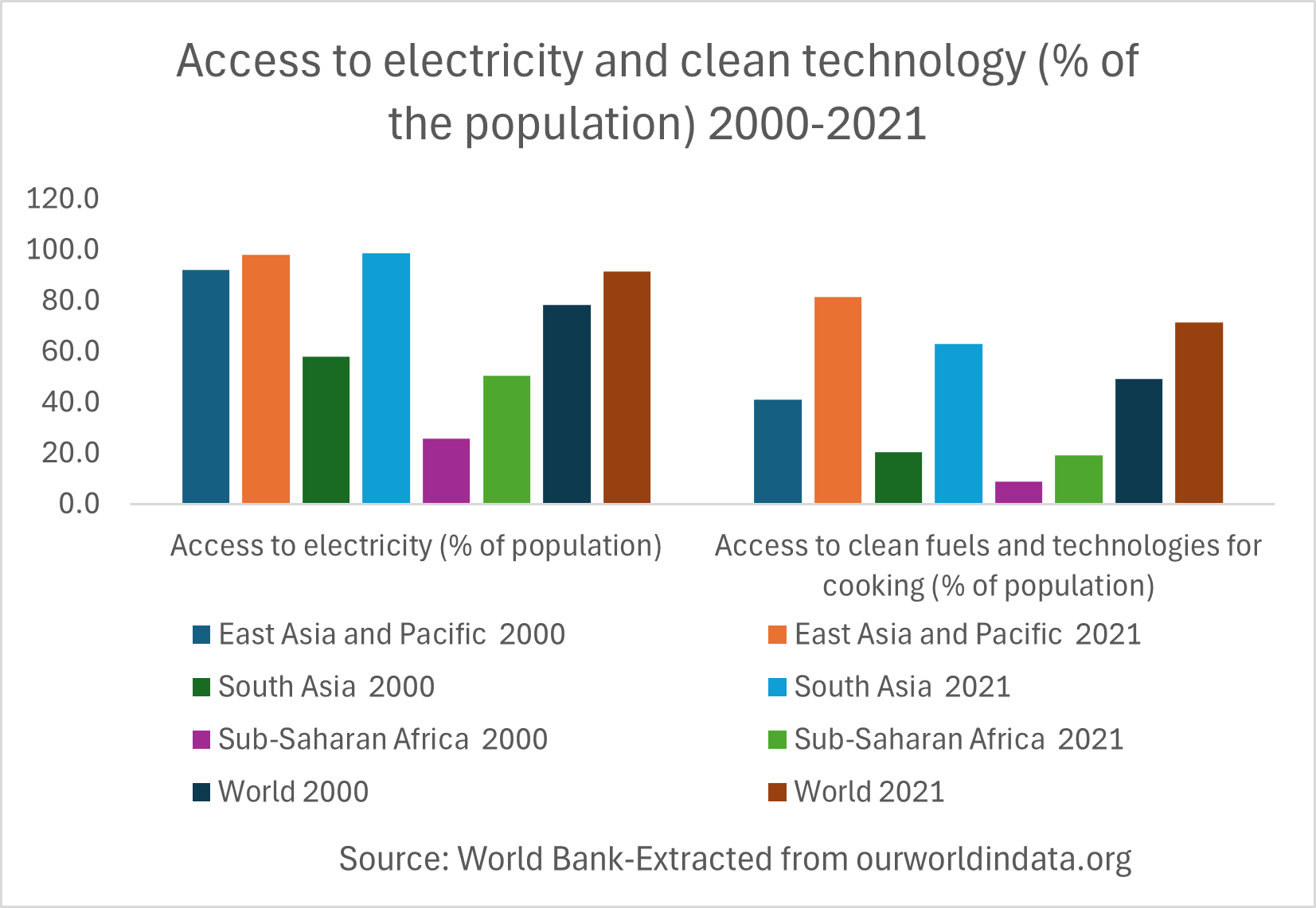

Lowest access to basic services , 2000 to 2022

Access to electricity as a percentage of the population highlights a significant challenge in Sub-Saharan Africa where the proportion of individuals with electricity access increased from 25.7 percent in 2000 to only 50.58 percent in 2021. In stark contrast, regions such as East Asia and the Pacific experienced a substantial rise from 92.1 percent to 98.2 percent, and South Asia saw a remarkable surge from 57.9 percent to 98.76 percent. On a global scale, the improvement from 78.4 percent to 91.4 percent emphasizes the urgent need for targeted efforts in Sub-Saharan Africa, where many continue to face barriers in accessing this vital resource that has the potential to transform lives and elevate communities. Access to clean fuels and cooking technologies in Sub-Saharan Africa has improved from 8.9 percent in 2000 to 19.11 percent in 2021, indicating a modest enhancement in living standards. Meanwhile, East Asia and the Pacific recorded a dramatic increase from 41.04 percent to 81.5 percent, and South Asia experienced a significant rise from 20.40 percent to 62.9 percent during the same timeframe. Globally, access improved from 49.1 percent to 71.3 percent. Despite these advancements, Sub-Saharan Africa lags considerably, revealing ongoing challenges in securing this essential resource and raising critical questions about the underlying factors at play.

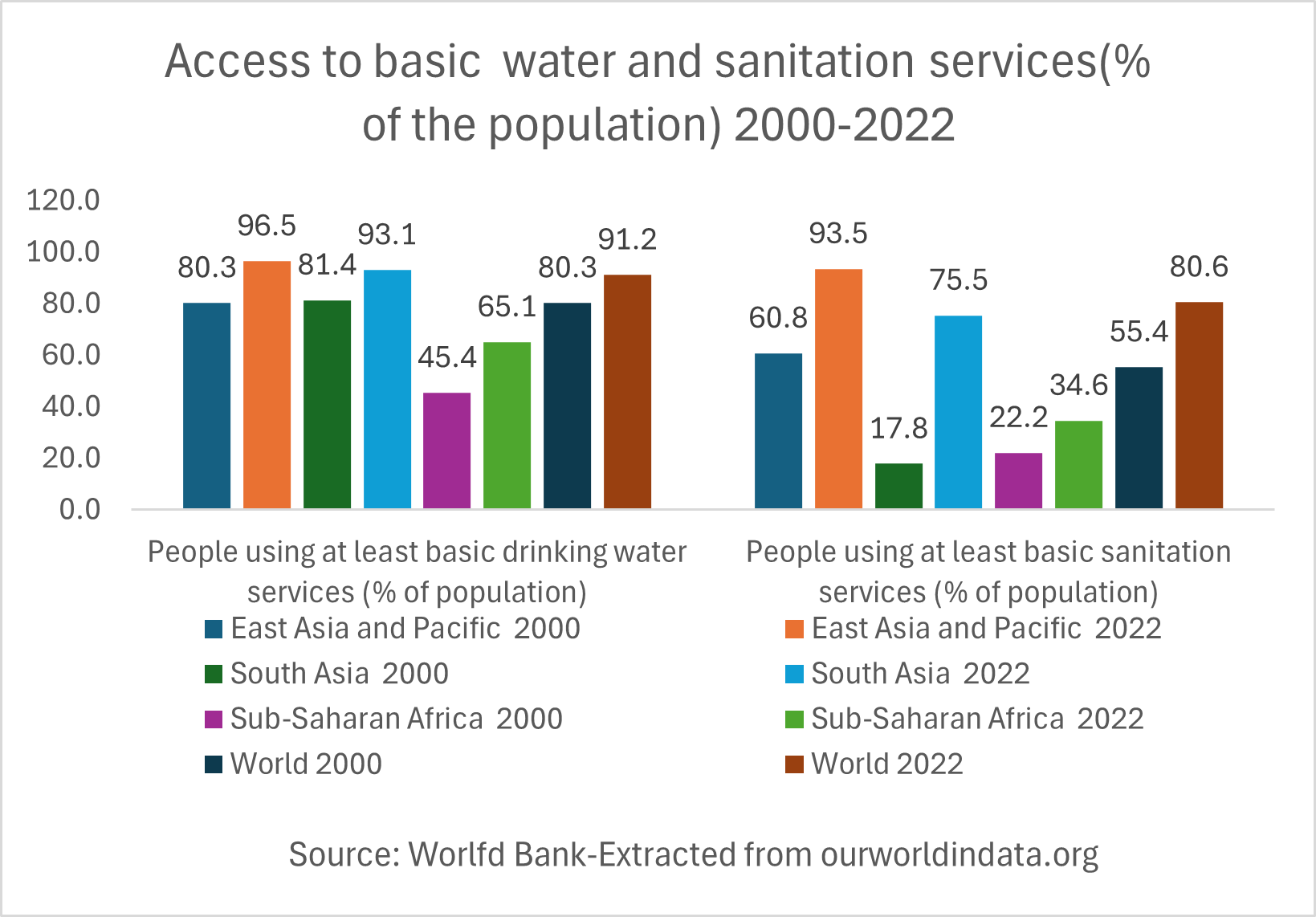

Lowest access to basic drinking water and basic sanitation, 2000 to 2022

In Sub-Saharan Africa, access to basic drinking water services rose from 45.4 percent in 2000 to 65.1 percent in 2022, illustrating a substantial yet insufficient improvement when compared to regions like East Asia and the Pacific, where access surged from 80.3 percent to 96.5 percent in the same timeframe, and South Asia, which experienced an increase from 81.4 percent to 93.1 percent. This global perspective reveals that the proportion of individuals gaining access to basic drinking water services grew from 80.3 percent to 91.2 percent, highlighting ongoing challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa in securing this vital resource and the urgent necessity for targeted interventions in the region, particularly in contrast to other developing areas. Additionally, access to basic sanitation services in Sub-Saharan Africa improved from 22.2 percent in 2000 to 34.6 percent in 2022, yet this progress pales in comparison to the significant gains seen in East Asia and the Pacific, which leaped from 60.8 percent to 93.5 percent, and South Asia, which saw an extraordinary rise from 17.8 percent to 75.5 percent. On a broader scale, global access to basic sanitation services advanced from 55.4 percent to 80.6 percent, signifying a pressing need for continued efforts to enhance these essential services in Sub-Saharan Africa.

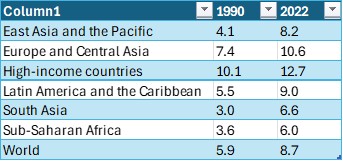

Lowest participation rate in formal education for adult over 25 years

Highest number of children out of school ,2000 to 2023

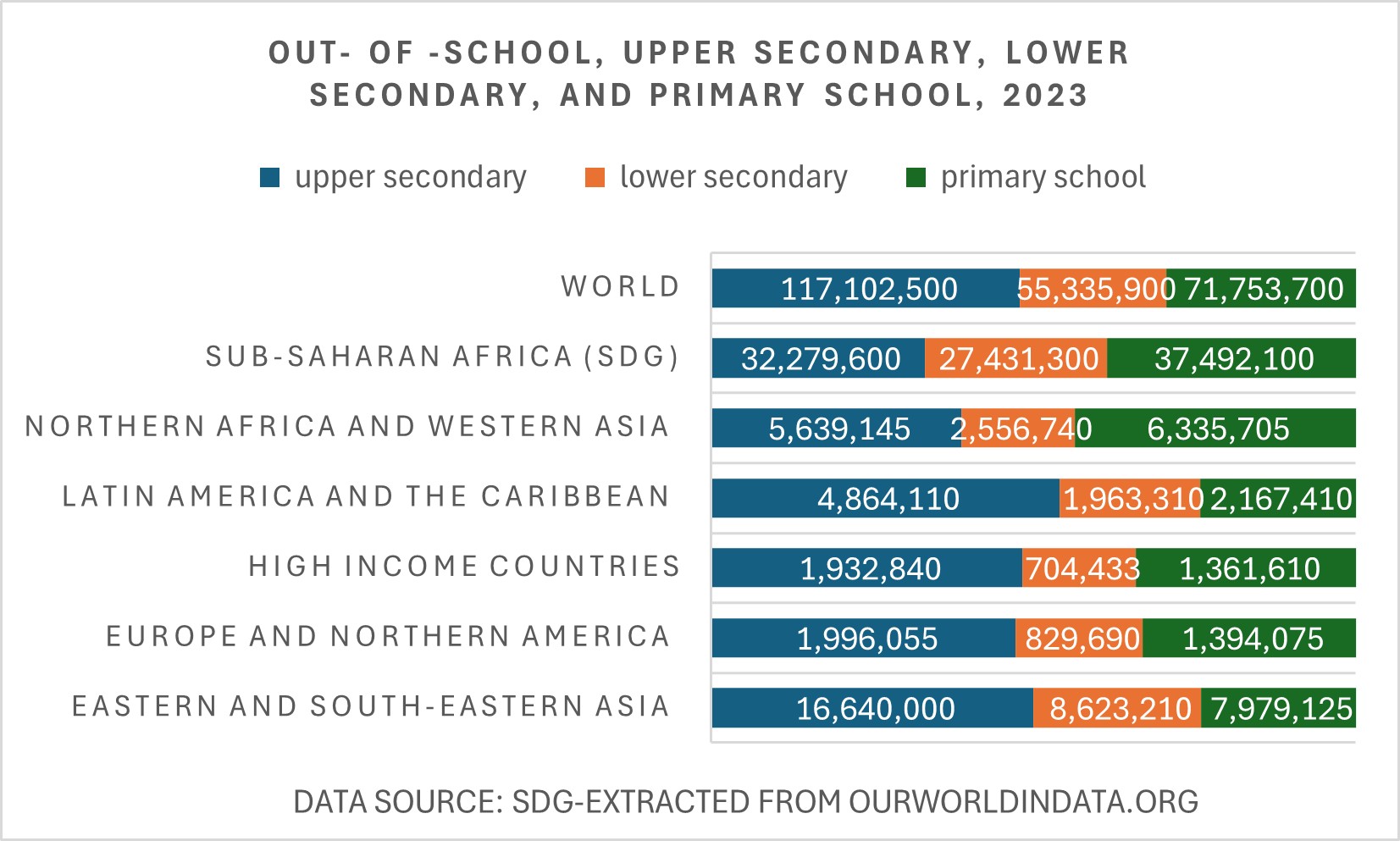

The education landscape has undergone notable changes worldwide, revealing both obstacles and advances. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the number of out-of-school youth aged in upper secondary school rose sharply from 24.6 million in 2000 to 32.3 million in 2023, while the number of out-of-school adolescents increased from 22.9 million to 27.4 million in the same timeframe. However, there was a slight improvement for primary school-aged children, with numbers decreasing from 39.2 million to 37.5 million. In contrast, Eastern and South-Eastern Asia saw a significant decline; out-of-school youth in upper secondary education fell from 43.7 million to 16.7 million, and out-of-school adolescents dropped from 17.5 million to 8.6 million, with primary school-aged children decreasing from 12.4 million to 7.9 million. Globally, a similar positive trend emerged, as the number of out-of-school youth in upper secondary education decreased from 172.2 million in 2000 to 117.2 million in 2023, with out-of-school adolescents falling from 94.5 million to 55.3 million, and primary school-aged children dropping from 122.6 million to 71.8 million, highlighting a significant movement towards better educational access and equity around the worldexcept in Sub-Saharan Africa.

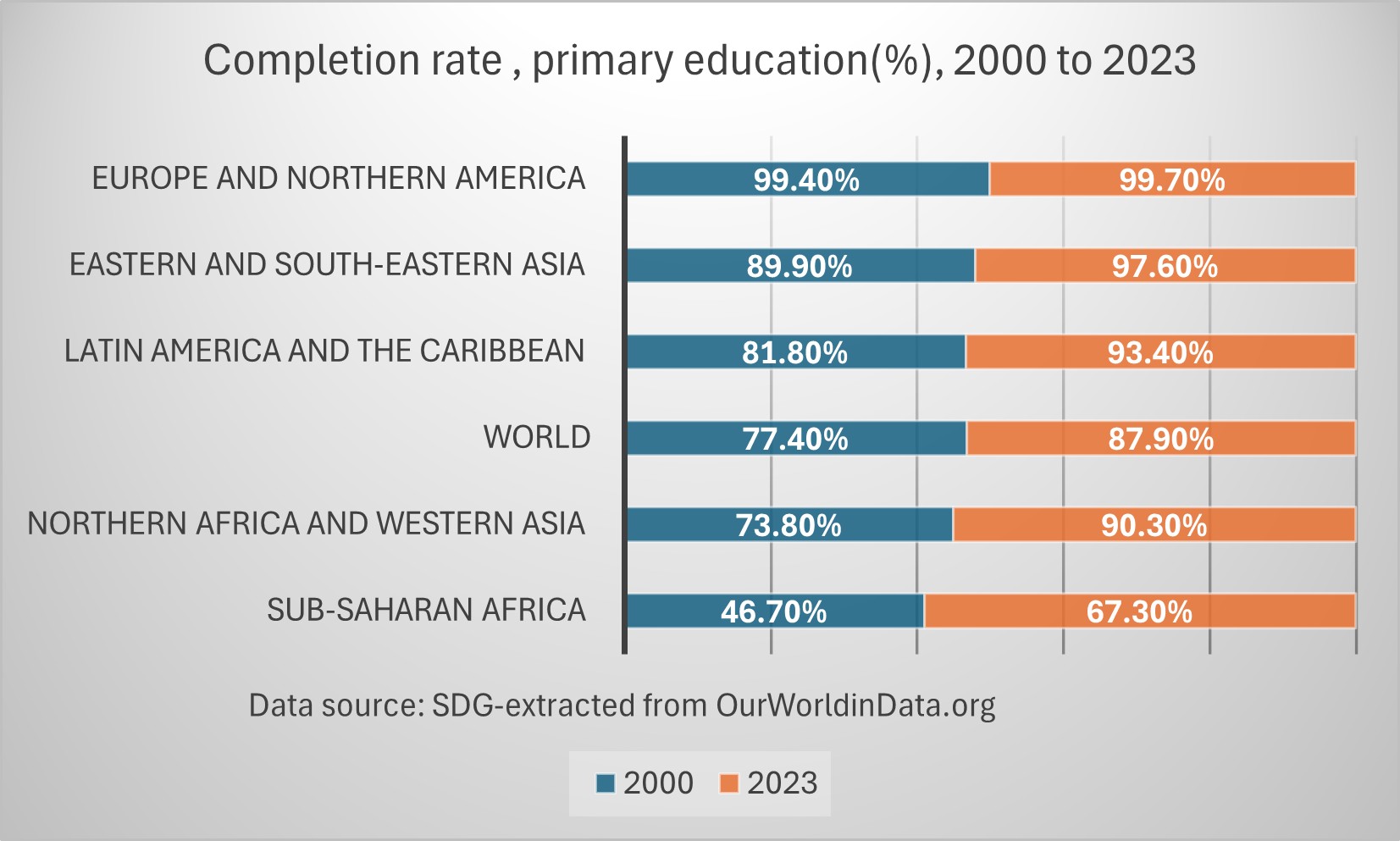

Lowest completion rate of primary education, 2000 to 2023

Share of people 3-5 years above the expected age of completion that have completed their primary education

In Sub-Saharan Africa, completion rate of primary education increased from 46.70% in 2000 to 67.30% in 2023, an absolute change of +20.6pp and a a relative change of 44%. In Northern Africa and Western Asia completion rate of primary education increased from 73.80% to 90.30%, an absolute change of +16.5 pp and a reo 97.60% in 2lative change of 22%. In Latin America and the Caribbean, completion rate of primary education increased from 81.80% in 2000 to 93.40% in 2023, an absolute change of +11.6pp and a relative change of 14%. In Eastern and South-Eastern Asia, completion rate of primary education increased from 89.90% in 2000 to 97.60% in 2023, an absolute change of +0.4pp and a relative change of 0%. In High income countries, completion rate of primary education increased from 99.30% in 2000 to 99.70% in 2023, an absolute change of +0.4pp and a relative change of 0%. In Europe and Northern America, completion rate of primary education increased from 99.40% in 2000 to 99.70% in 2023, an absolute change of +0.3pp and a a relative change of 0%.

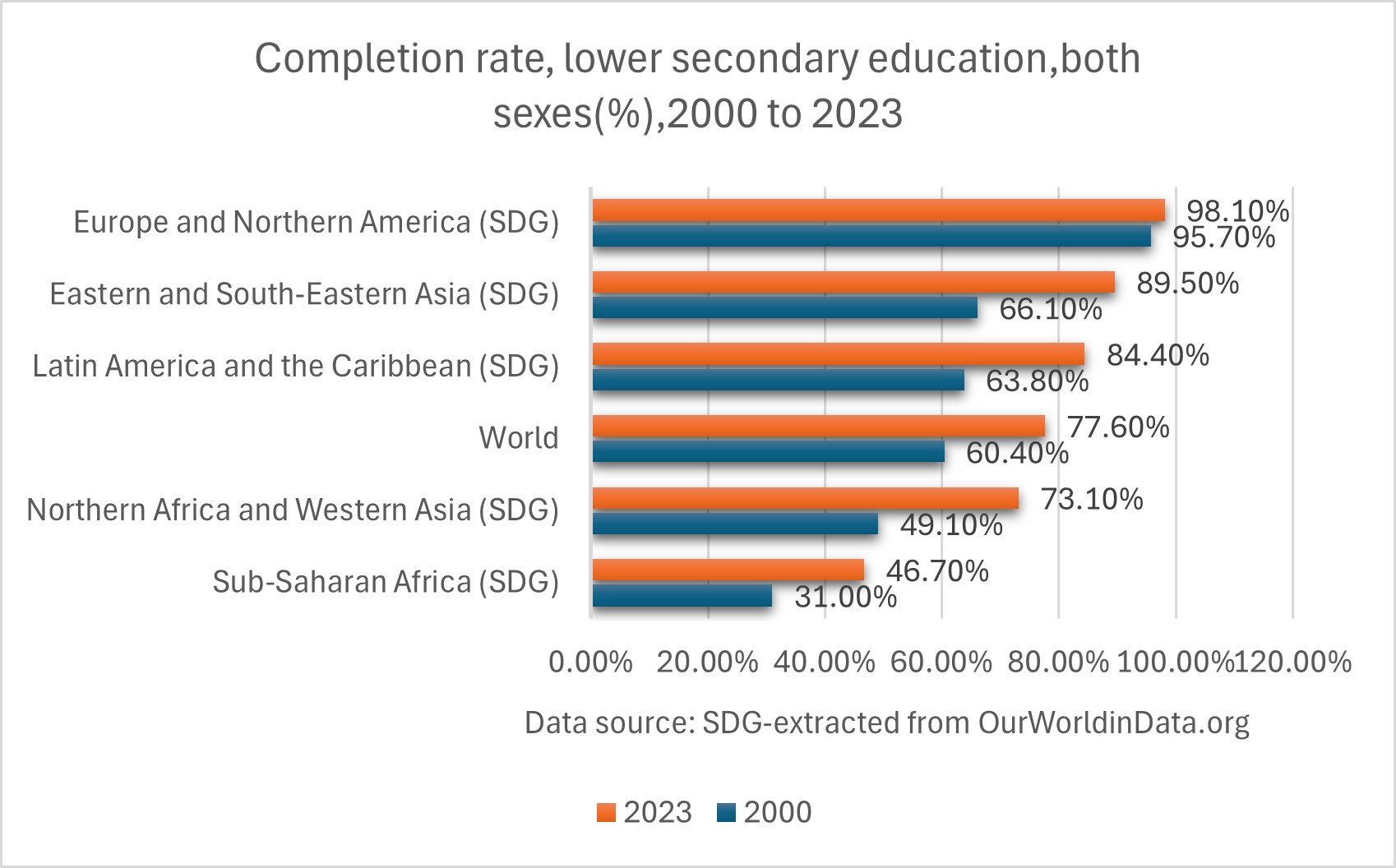

Lowest completion rate of lower – secondary education, 2000 to 2023

In Sub-Saharan Africa, the completion rate of lower-secondary education saw a significant rise from 31.00% in 2000 to 46.70% in 2023, reflecting an absolute increase of 15.7 percentage points and a relative change of 51%. Similarly, in Northern Africa and Western Asia, the completion rate improved from 49.10% in 2000 to 73.10% in 2023, marking an absolute change of 24.0 percentage points and a relative increase of 49%. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the completion rate rose from 63.80% in 2000 to 84.40% in 2023, translating to an absolute change of 20.6 percentage points and a relative increase of 32%. Eastern and South-Eastern Asia experienced an increase in completion rates from 66.10% in 2000 to 89.50% in 2023, with an absolute change of 23.4 percentage points and a relative change of 35%. In high-income countries, the completion rate rose modestly from 94.90% in 2000 to 97.70% in 2023, showing an absolute change of 2.8 percentage points and a relative change of 3%. Lastly, in Europe and Northern America, the completion rate increased from 95.70% in 2000 to 98.10% in 2023, which represents an absolute change of 2.4 percentage points and a relative increase of 3%.

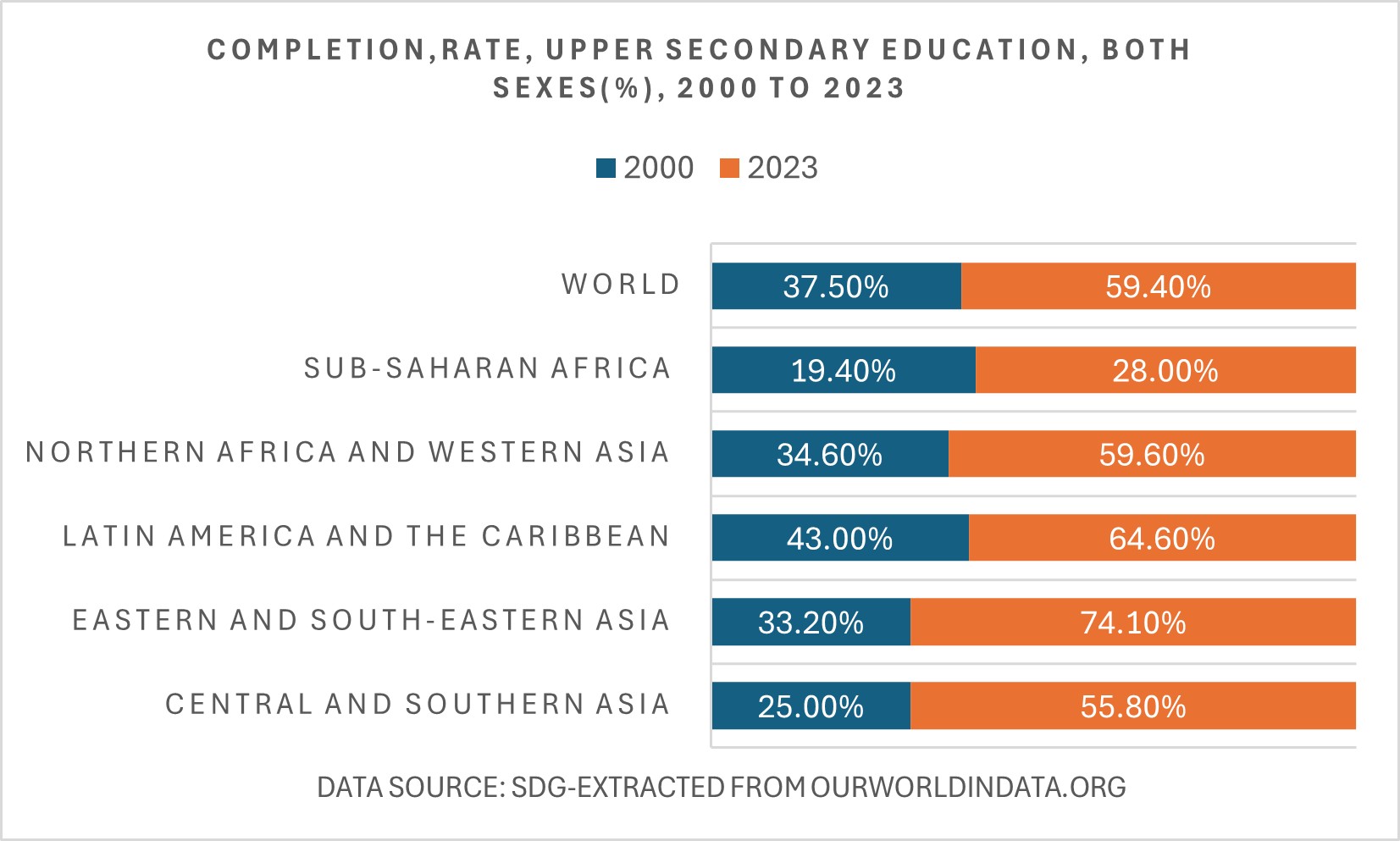

Lowest completion rate of upper-secondary education, 2000 to 2023

In recent years, the global landscape of upper-secondary education completion has seen notable progress, although disparities remain evident. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the completion rate rose from 19.40% in 2000 to 28.00% in 2023, reflecting an absolute change of 8.6 percentage points and a relative increase of 44%. Meanwhile, Northern Africa and Western Asia experienced a significant rise from 34.60% to 59.60%, marking a 25 percentage point increase and a 72% relative change. Latin America and the Caribbean also demonstrated improvement, with completion rates climbing from 43.00% to 64.60%, an increase of 21.6 percentage points, equivalent to a relative change of 50%. Eastern and South-Eastern Asia showed remarkable progress, with rates soaring from 33.20% to 74.10%, representing an absolute change of 40.9 percentage points and a staggering relative increase of 123%. In contrast, high-income countries had a more modest increase from 82.30% to 88.80%, resulting in a change of 6.5 percentage points and a relative growth of 8%. Overall, the global completion rate improved from 37.50% in 2000 to 59.40% in 2023, indicating an absolute increase of 21.9 percentage points and a relative change of 58%.

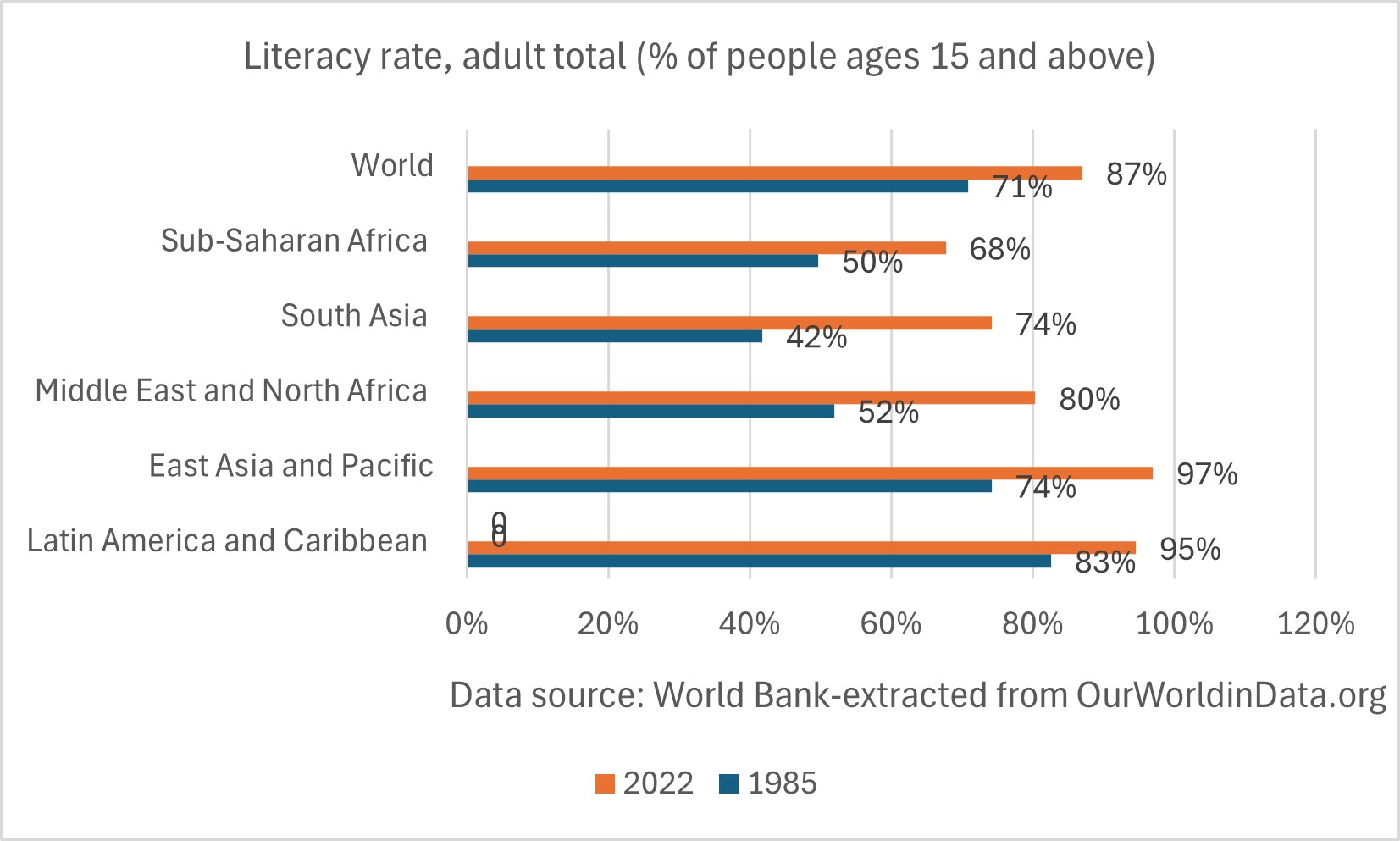

Highest adult illiteracy rate, 1985 to 2022

The global landscape of adult literacy has seen significant improvements over the years, particularly among individuals aged 15 and older. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the literacy rate rose markedly from 49.67% in 1985 to 67.93% in 2022. East Asia and the Pacific experienced an impressive rise from 74% to 97% within the same timeframe. Europe and Central Asia maintained a high literacy rate of 98.54% in 2022, while Latin America and the Caribbean increased their rates from 82.57% to 94.60%. The Middle East and North Africa also benefited from a rise in literacy, which improved from 51.94% to 80.36%. South Asia’s literacy rate advanced from 41.79% to 74.19%, contributing to a global increase from 70.80% to 87.01%.

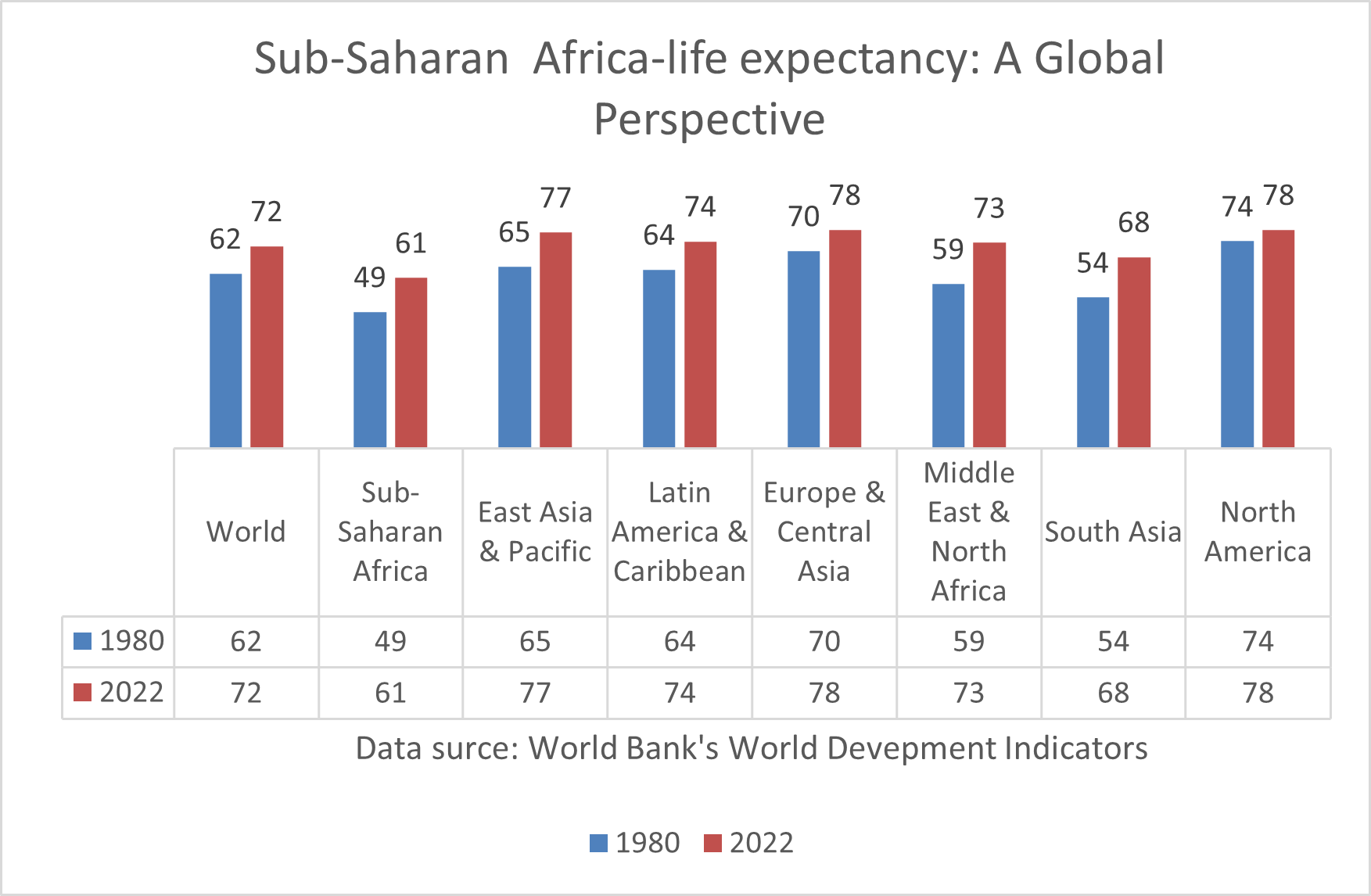

Lowest life expectancy in Developing world,, 1980-2022

The analysis of life expectancy over the past seventy years shows that while the world has made significant progress, Sub-Saharan Africa has seen only slight improvements. From 1980 to 2022, global life expectancy for newborns increased from 62 years to 72 years, whereas in Sub-Saharan Africa, it only climbed from 49 years to 61 years. In comparison, East Asia and South Asia have made impressive gains, with life expectancies rising from 65 to 77 years and 54 to 68 years, respectively. These differences highlight the ongoing challenges faced by Sub-Saharan communities and remind us of our shared responsibility to work towards a healthier future for all in the region.

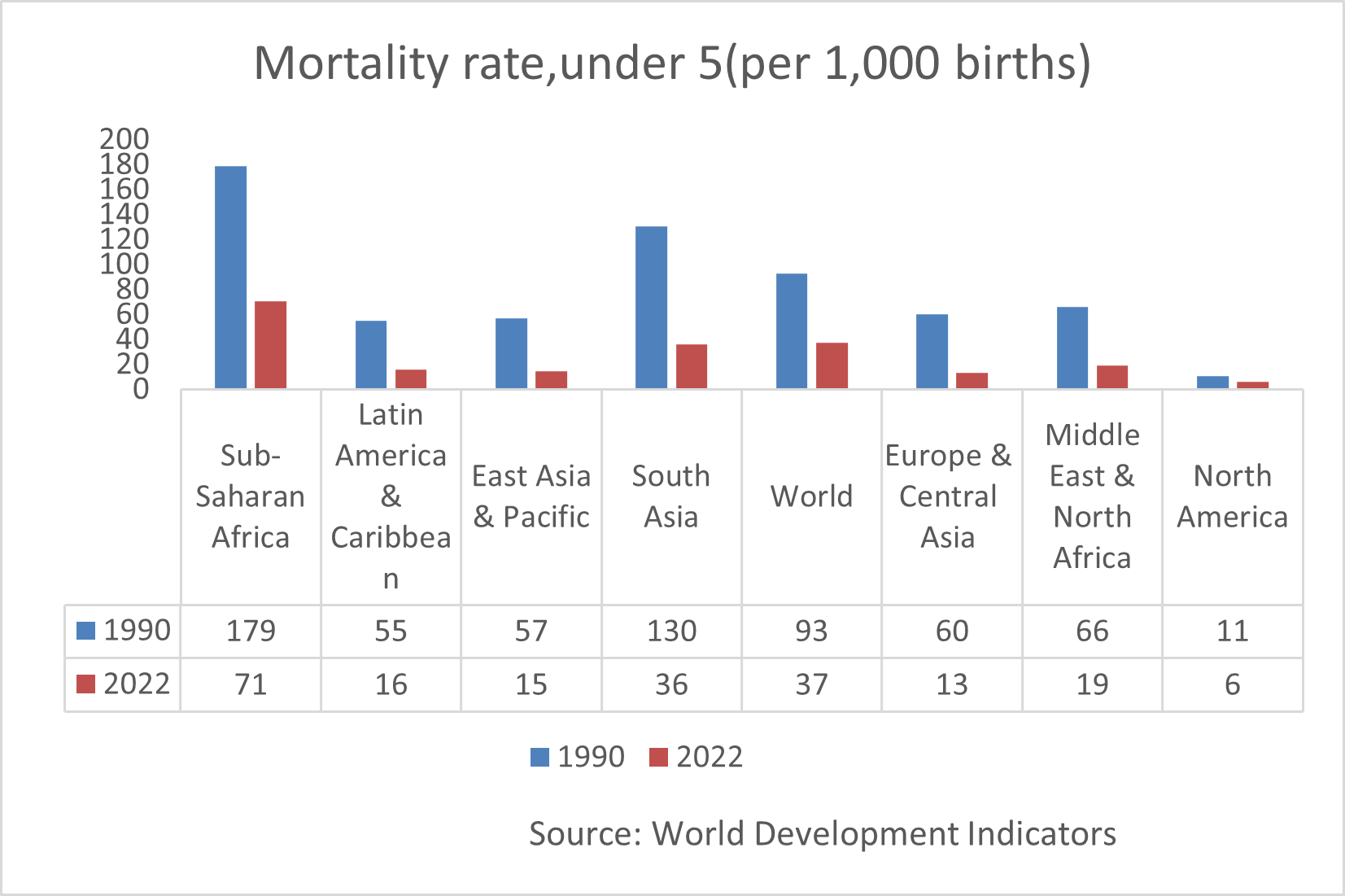

Highest under-5 mortality rate in Developing world

Since 1950, global child mortality rates have significantly declined, reflecting improved living standards, healthcare access, nutrition, and safe drinking water. In wealthy regions like Europe and North America, rates are now below seven percent, showcasing the success of public health initiatives. However, Sub-Saharan Africa still lags, with child mortality dropping from 179 per 1000 live births in 1990 to 71 in 2022, while East Asia and the Pacific saw reductions from 57 to 15, and South Asia from 130 to 36. Overall, global child mortality rates fell from 93 per 1000 live births in 1990 to 37 in 2022, underscoring the urgent need for improved health outcomes for children in Sub-Saharan Africa.

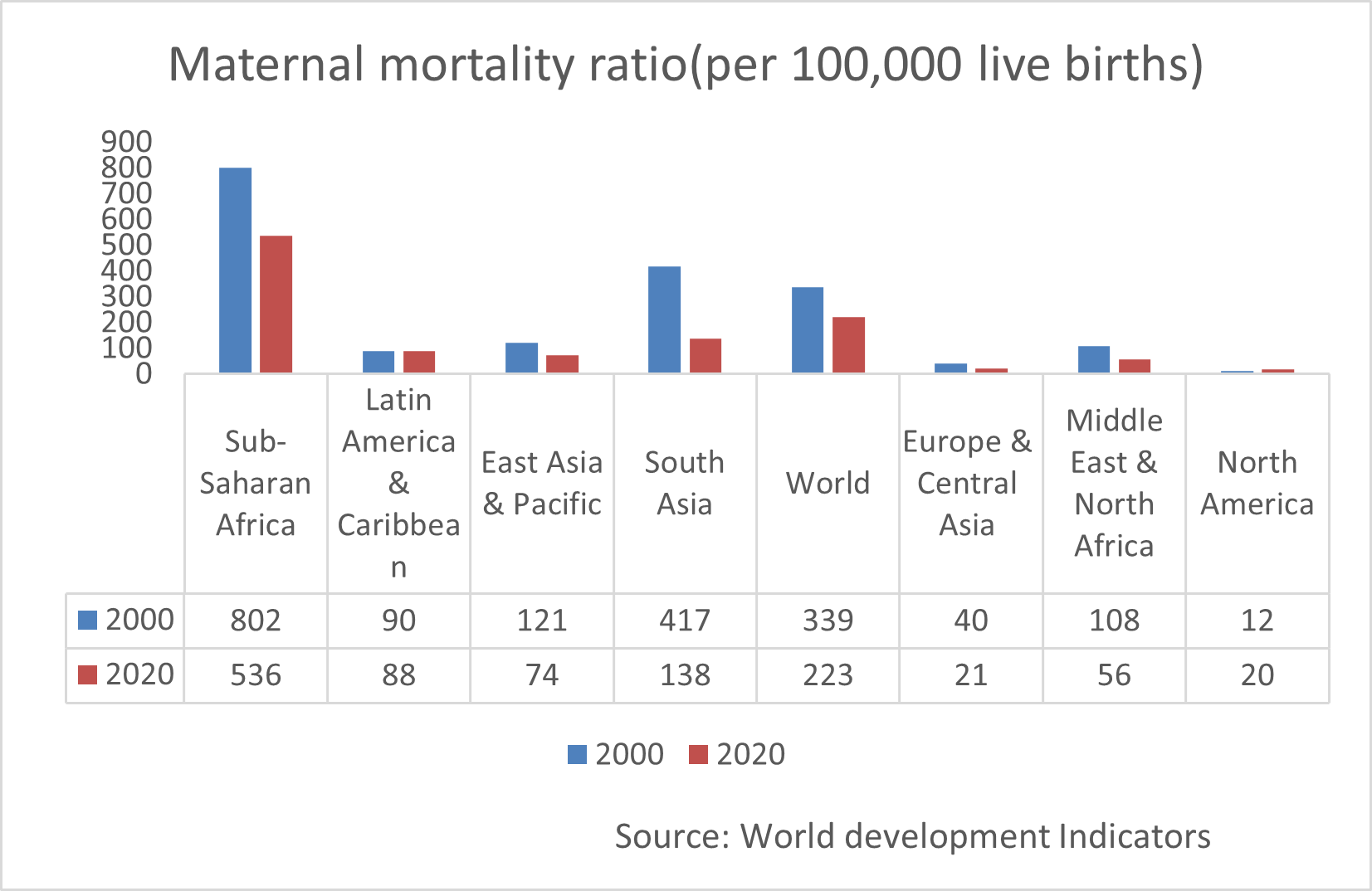

Highest maternal morality ratio in Developing World

Pregnancy-related fatalities reveal significant regional disparities, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, where elevated birth rates contribute to a troubling rate of maternal mortality. The reduction in maternal deaths in this region, from 802 in 2000 to 536 in 2020, underscores the pressing need for improved healthcare systems to safeguard mothers and infants. In contrast, East Asia and the Pacific, along with South Asia, have made considerable strides in this regard, with East Asia and the Pacific reducing maternal deaths from 121 to 74 and South Asia from 417 to 138 during the same timeframe. These achievements demonstrate the possibility of substantial progress through effective governance and healthcare policies, offering hope to families striving for healthier futures.

HIGHEST NUMBER OF COUPS IN THE WORLD

COUPS IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA BY COUNTRY SINCE 1950

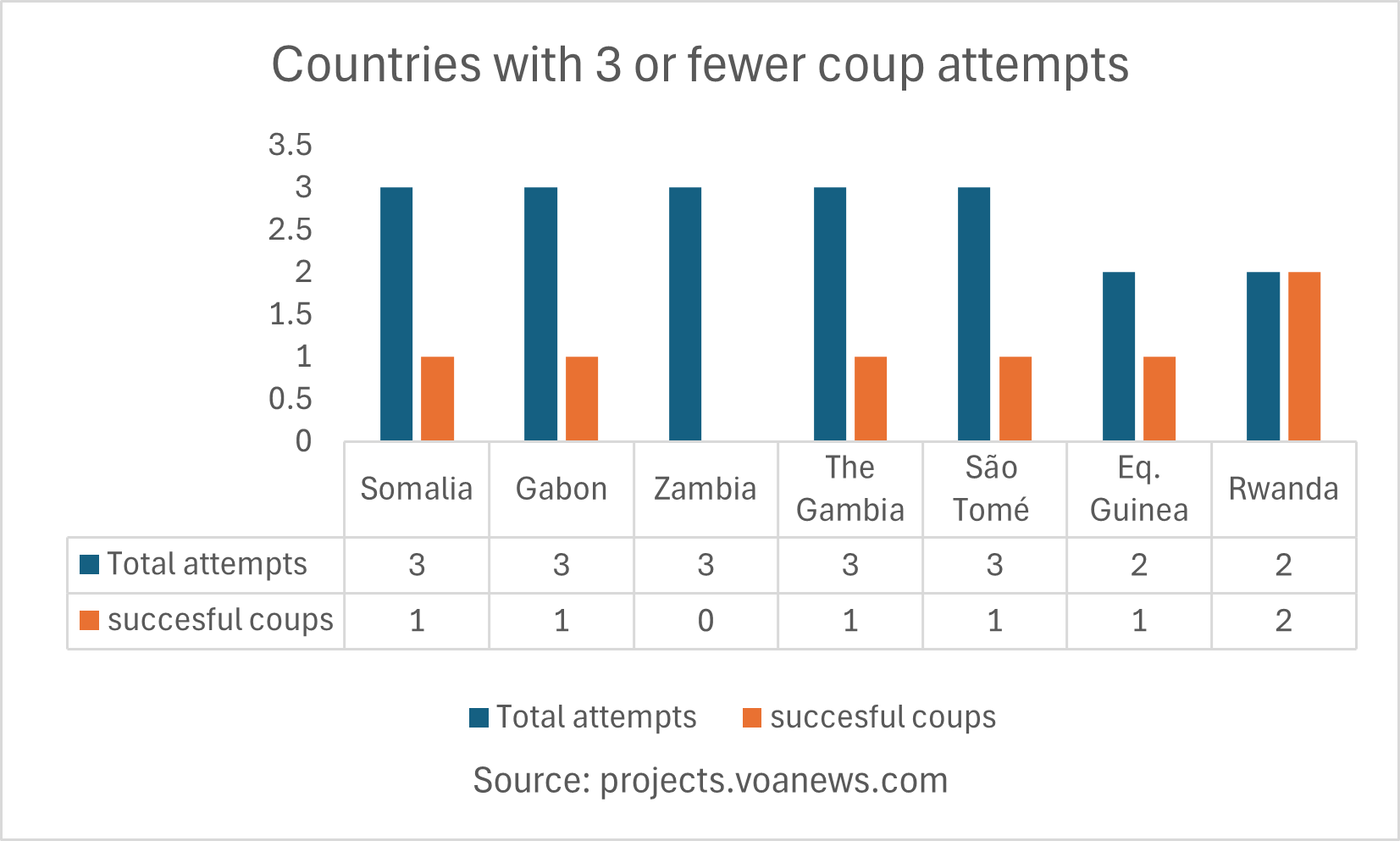

Countries with 3 or fewer coup attempts

- Somalia: 3 attempts, 1 successful

- Gabon: 3 attempts, 1 successful

- Zambia: 3 attempts, 0 successful

- The Gambia: 3 attempts, 1 successful

- São Tomé: 3 attempts, 1 successful

- Eq. Guinea: 2 attempts, 1 successful

- Rwanda: 2 attempts, 2 successful

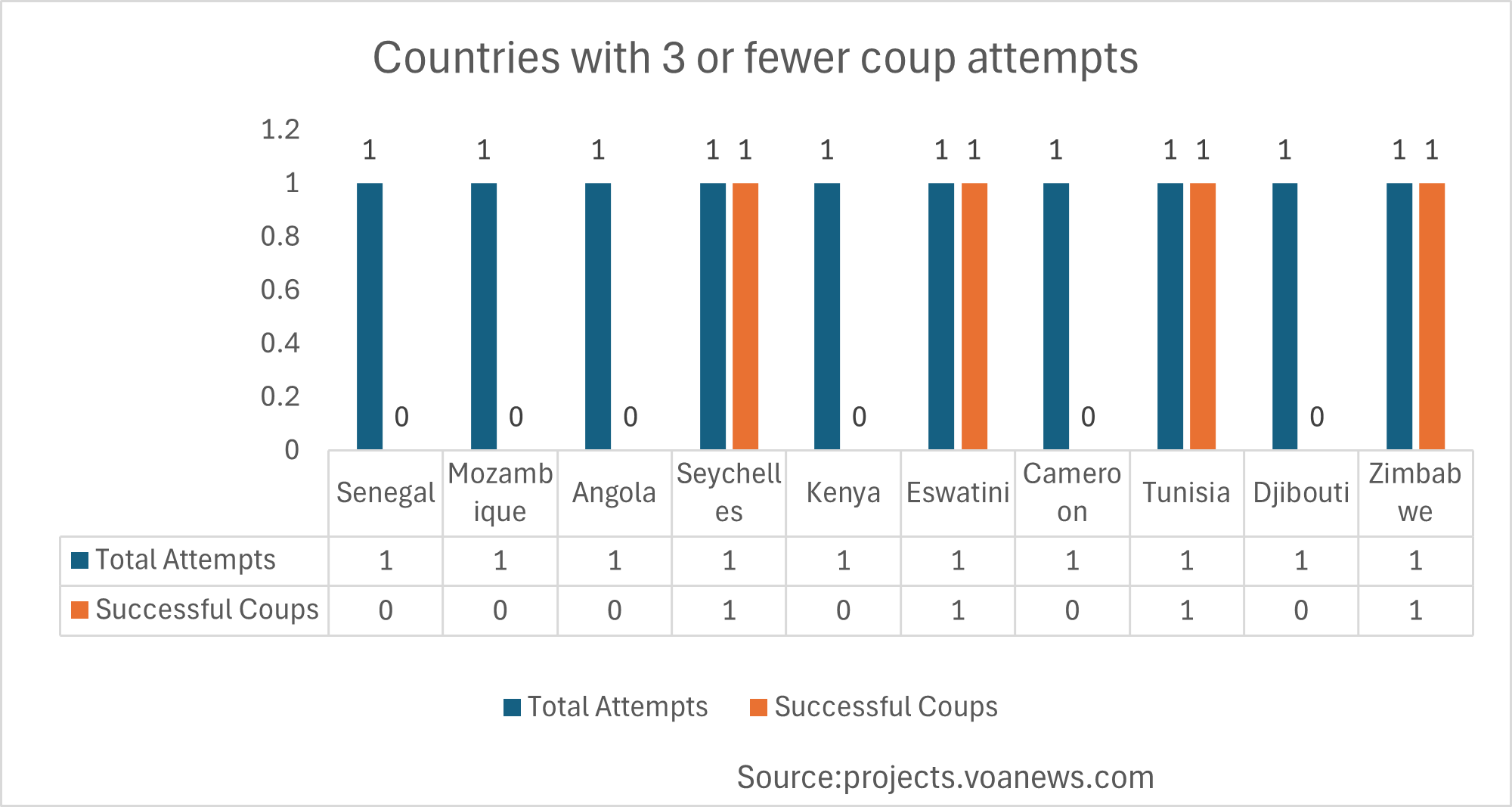

Countries with 3 or fewer coup attempts

- Senegal: 1 attempt, 0 successful

- Mozambique: 1 attempt, 0 successful

- Angola: 1 attempt, 0 successful

- Seychelles: 1 attempt, 1 successful

- Kenya: 1 attempt, 0 successful

- Eswatini: 1 attempt, 1 successful

- Cameroon: 1 attempt, 0 successful

- Djibouti: 1 attempt, 0 successful

- Zimbabwe: 1 attempt, 1 successful

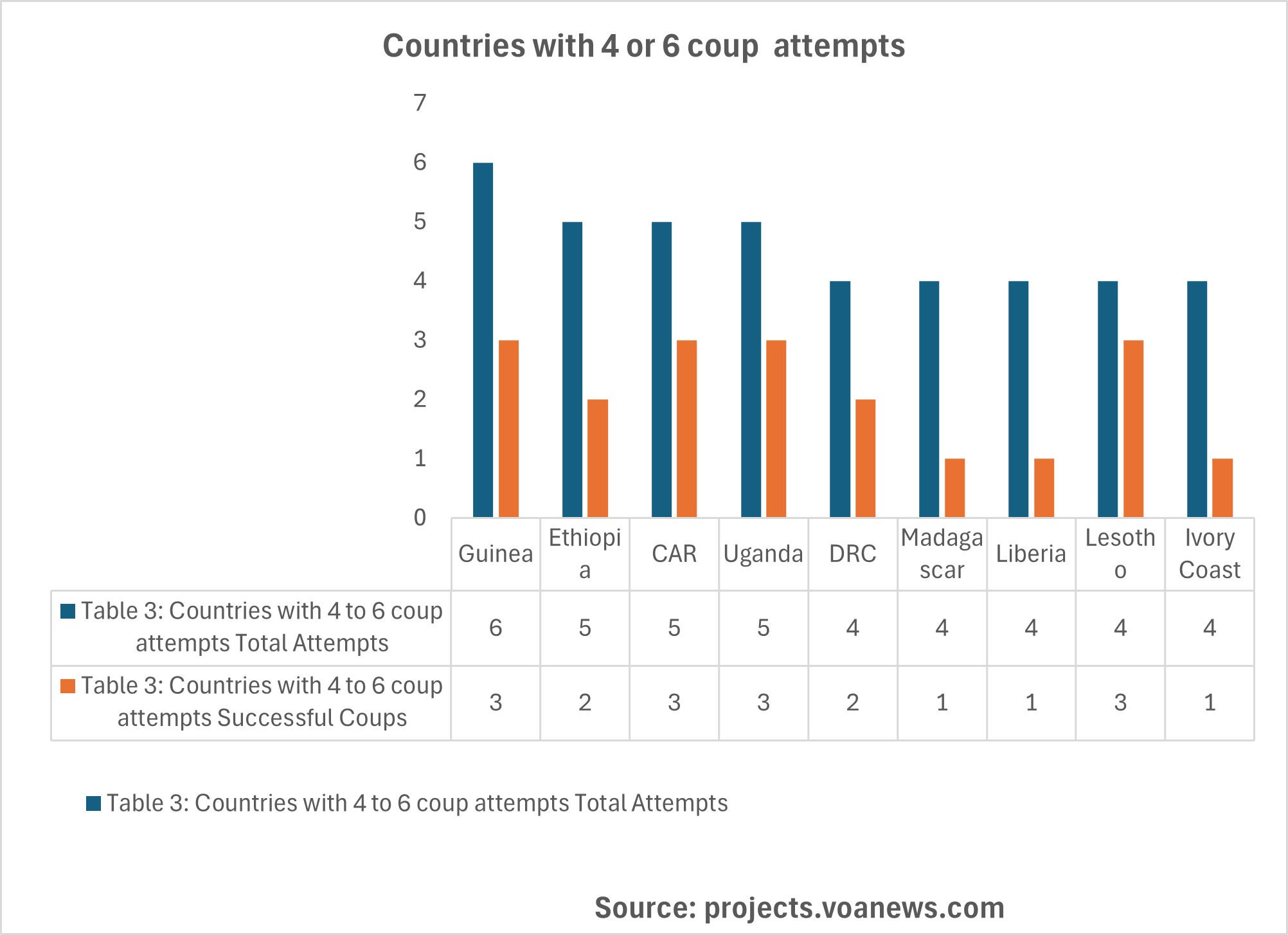

Countries with 4 to 6 coup attempts

- Guinea: 6 attempts, 3 successful

- Ethiopia: 5 attempts, 2 successful

- CAR: 5 attempts, 3 successful

- Uganda: 5 attempts, 3 successful

- DRC: 4 attempts, 2 successful

- Madagascar: 4 attempts, 1 successful

- Liberia: 4 attempts, 1 successful

- Lesotho: 4 attempts, 3 successful

- Ivory Coast: 4 attempts, 1 successful

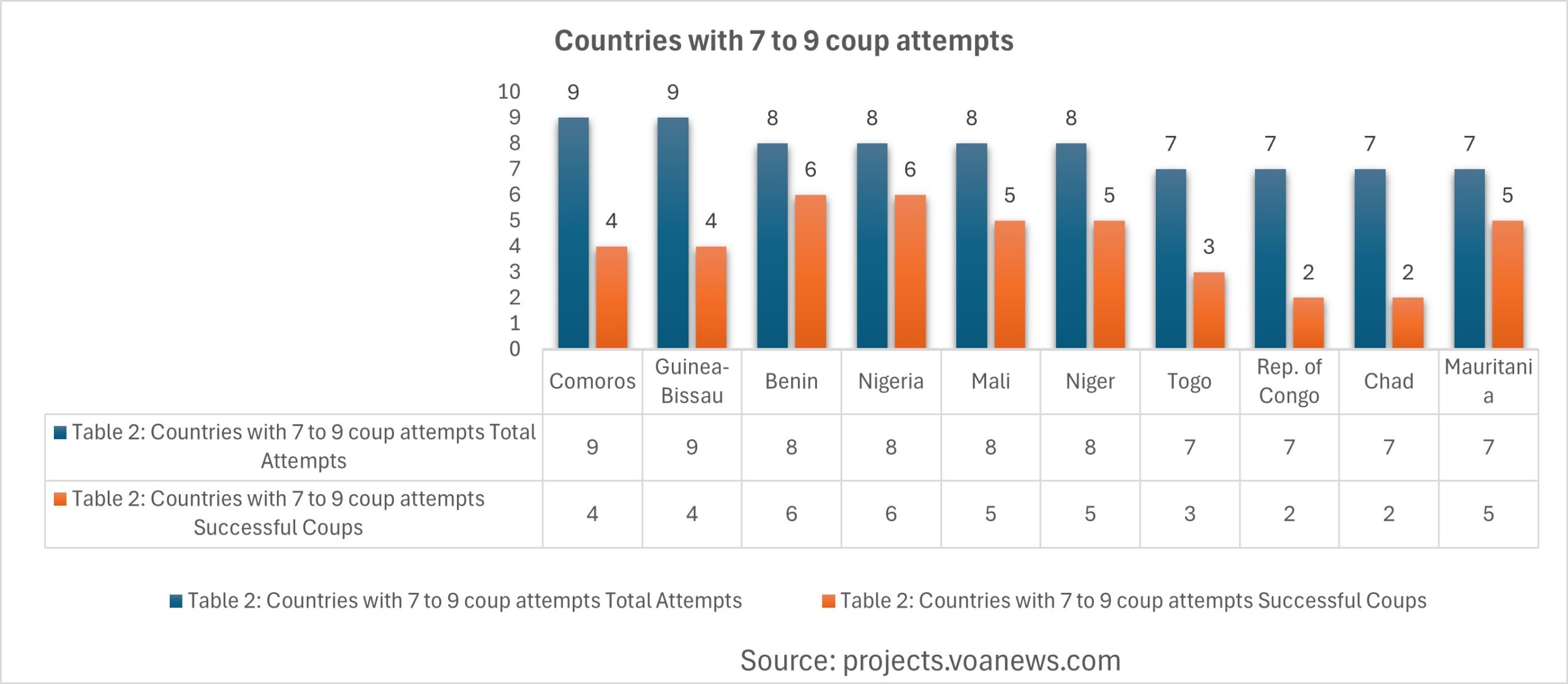

Countries with 7 to 9 coup attempts

- Comoros: 9 attempts, 4 successful

- Guinea-Bissau: 9 attempts, 4 successful

- Benin: 8 attempts, 6 successful

- Nigeria: 8 attempts, 6 successful

- Mali: 8 attempts, 5 successful

- Niger: 8 attempts, 5 successful

- Togo: 7 attempts, 3 successful

- Rep. of Congo: 7 attempts, 2 successful

- Chad: 7 attempts, 2 successful

- Mauritania: 7 attempts, 5 successful

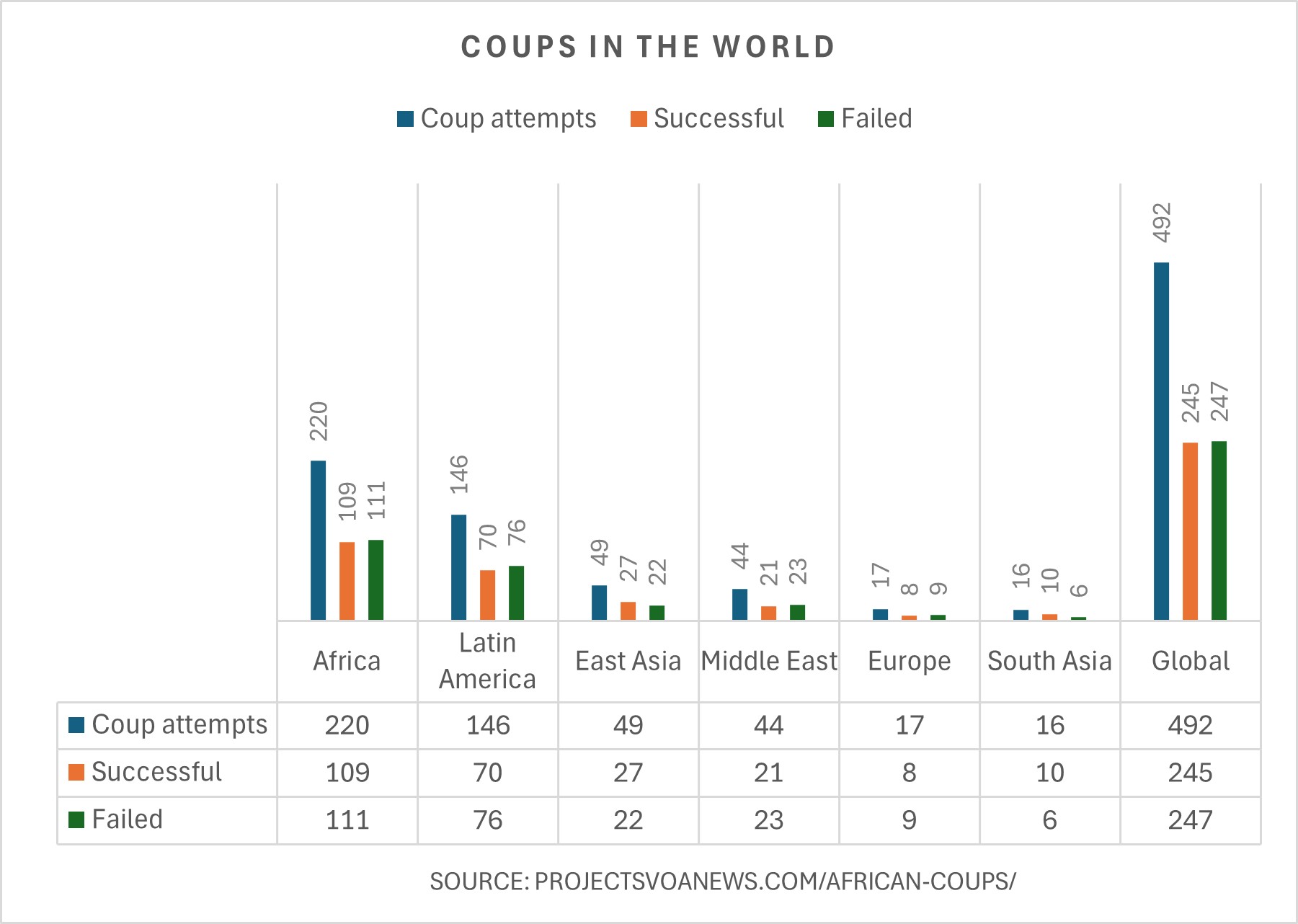

Coups in the World

Africa Compared to the world

Of 492 attempted or successful coups carried out around the world since 1950, Africa has seen 220, the most of any region, with 109 of them successful, Powell and Thyne’s data show (see https://projectsvoanews.com/afrfican-coups/).

Countries with 10 or more coup attempts

- Sudan: 18 attempts, 6 successful

- Burundi: 11 attempts, 5 successful

- Burkina Faso: 10 attempts, 9 successful

- Ghana: 10 attempts, 5 successful

- Sierra Leone: 10 attempts, 5 successful

HIGHEST CIVIL CONFLICTS IN DEVELOPING WORLD

Post-Colonial Conflicts

Economic Factors

Ethnic and Political Tensions

Proxy Wars and External Influence

Recent Conflicts

List of Conflicts in Sub-Saharan Africa

Below is a comprehensive overview of conflicts occurring in Sub-Saharan Africa and its nearby islands. This includes wars among African nations, civil wars, as well as struggles for independence, secessionist movements, and separatist disputes. Additionally, it covers significant instances of national unrest such as riots and massacres. For an extensive list of conflicts within Africa, please visit wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_conflicts_in_Africa.

African Great Lakes

Burundi

- October 18 – 19, 1965 1965 Burundian coup attempt

- July 8, 1966 July 1966 Burundian coup d’état

- November 28, 1966 November 1966 Burundian coup d’état

- 1972 Burundi genocide

- November 1, 1976 1976 Burundian coup d’état

- September 3, 1987 1987 Burundian coup d’état

- 1993 – 2005 Burundi Civil War

- October 21 – November 1993 1993 Burundian coup attempt

- July 25, 1996 1996 Burundian coup d’état

- December 28, 2000 Titanic Express Massacre

- April 18, 2001 2001 Burundian coup attempt

- September 9, 2002 Itaba Massacre

- August 13, 2004 Gatumba Massacre

- 2015–2018 Burundian unrest

- May 13 – 15, 2015 2015 Burundian coup attempt

Rwanda

- November 1, 1959 – July 1, 1961 Rwandan Revolution

- January 28, 1961 Coup of Gitarama

- 1963 Bugesera invasion

- July 5, 1973 1973 Rwandan coup d’état

- 1990 – 1994 Rwandan Civil War

- April 7, 1994 – July 15, 1994 Rwandan genocide

Kenya

- 1963 – present Somali–Kenyan conflict

- 1963 – 1967 Shifta War

- October 25, 1969 Kisumu massacre

- 1980 Garissa Massacre

- August 1, 1982 1982 Kenyan coup attempt

- February 10, 1984 Wagalla massacre

- 1987 – 1990 Kenyan-Ugandan border conflict

- 1998 – present Terrorism in Kenya

- September 21 – 24, 2013 Westgate shopping mall attack

- 2005 Turbi Village Massacre

- 2005 – 2008 Mount Elgon insurgency

- August 22, 2012 2012–2013 Tana River District clashes

- November 2012 Baragoi clashes

South Sudan

- 1955 – 1972 First Sudanese Civil War

- August 18–30, 1955 Torit mutiny

- 1983 – 2005 Second Sudanese Civil War

- 9 March – April 1997 Operation Thunderbolt (1997)

- June 2000 – August 2001 War of the Peters

- 1987 – present Lord’s Resistance Army insurgency

- 2005 – 2006 Disarmament of the Lou Nuer

- 2006 Battle of Malakal

- 2008 – ongoing Sudanese nomadic conflicts

- 2010 – 2011 George Athor’s rebellion

- 2008 – present Sudanese nomadic conflicts

- 2011 – ongoing Ethnic violence in South Sudan (2011–present)

- 2011 – 2020 Sudanese conflict in South Kordofan and Blue Nile

- 2012 Heglig Crisis

- 2013 – 2020 South Sudanese Civil War

- 2022– present Abyei border conflict (2022–present)

Tanzania

- 1964 Zanzibar Revolution

- 1972 1972 invasion of Uganda

- 1978 – 1979 Uganda–Tanzania War

Uganda

- 1966 Mengo Crisis

- January 25, 1971 1971 Ugandan coup d’état

- 1972 1972 invasion of Uganda

- 1974 Arube uprising

- 1976 Operation Entebbe

- 1977 Operation Mafuta Mingi

- 1977 1977 invasion of Uganda

- 1978 – 1979 Uganda-Tanzania War

- April 11, 1979 Fall of Kampala

- 1980 – 1986 Ugandan Bush War

July 27, 1985 1985 Ugandan coup d’état - January 26, 1986 Battle of Kampala

- 1986 – 1994 War in Uganda (1986-1994)

- 1987 – 1990 Kenyan-Ugandan border conflict

- 1987 – ongoing Lord’s Resistance Army insurgency

- 1996 – ongoing Allied Democratic Forces insurgency

- 1996 – 2002 UNRF II insurgency

- 2016 Kasese clashes

Central Africa

Cameroon

- 1955 – 1964 Cameroon War

- 1981 – present Bakassi conflict1981 – 2005 Nigerian-Cameroonian conflict over Bakassi2006 – 2018 First Bakassi insurgency2021 – present Pro-Biafran insurgency in Bakassi

- 6 February 2007 –ongoing Operation Juniper Shield

- 2009 – present Boko Haram insurgency

- 23 January – 24 December 2015 2015 West African offensive

- November 2018 – February 2020 Chad Basin campaign (2018–2020)

- 2017 – present Anglophone Crisis

- July 3, 2018 Battle of Batibo

- July 28, 2018 Ndop prison break

- September 25, 2018 Wum prison break

- 26 April – May 1, 2020 Operation Free Bafut

- 8 September 2020 – present Operation Bamenda Clean

- May – June 2021 Operation Bui Clean

- September 16, 2021 September 2021 Bamessing ambush

- July 31, 2022 Battle of Bambui

Central African Republic

- December, 31 1965 – January, 1 1966 Saint-Sylvestre coup d’état

- September 21, 1979 1979 Central African coup d’état

- September 1, 1981 1981 Central African Republic coup d’état

- March 3, 1982 1982 Central African Republic coup attempt

- 1987 – present Lord’s Resistance Army insurgency

- May 27 – 28, 2001 2001 Central African Republic coup attempt

- October 25 – 31, 2002 2002 Central African Republic coup attempt

- March 15, 2003 2003 Central African Republic coup d’état

- 2004 – 2007 Central African Republic Bush War

- 2012 – present Central African Republic Civil War (2012–present)

- March 22 – 23, 2013 Battle of Bangui (2013)

- 13 April 2013 – 10 January 2014 Central African Republic conflict under the Djotodia administration

Republic of Chad

- 1 November 1965 Mangalmé riots

- 1965 – 1979 Chadian Civil War (1965–1979)

- 1978 – 1987 Chadian–Libyan conflict

- 1983 – 1984 Operation Manta

- February 13, 1986 – August 1, 2014 Opération Épervier

- 1986 – 1987 Toyota War

- 1983 Chadian–Nigerian War

- December 2 – 3, 1990 1990 Chadian coup d’état

- 2002 – ongoing Insurgency in the Maghreb (2002–present)

- 6 February 2007 – ongoing Operation Juniper Shield

- May 16, 2004 2004 Chadian coup attempt

- 2005 – 2010 War in Chad

- 18 December 2005 Battle of Adré

- 6 January 2006 Raid on Borota

- 6 March 2006 Raid on Amdjereme

- 13 April 2006 Battle of N’Djamena (2006)

- 1 May 2006 Raid on Dalola

- 2–4 February 2008 Battle of N’Djamena (2008)

- 18 June 2008 Battle of Am Zoer

- 7 May 2009 Battle of Am Dam

- 24–28 April 2010 Battle of Tamassi

- 2009 – present Boko Haram insurgency

- 23 January – 24 December 2015 2015 West African offensive

- November 2018 – February 2020 Chad Basin campaign (2018–2020)

- May 1, 2013 2013 Chadian coup attempt

- 2016 – present Insurgency in Chad (2016–present)

- April 11 – May 9, 2021 2021 Northern Chad offensive

Republic of Congo

- 1665–1709 Kongo Civil War

- June 27 – July 6, 1966 1966 Republic of the Congo coup attempt

- September 4, 1968 1968 Republic of the Congo coup d’état

- February 22, 1972 1972 Republic of the Congo coup attempt

- July – September 1987 1987 Republic of the Congo coup attempt

- 1993 – 1994 Republic of the Congo Civil War (1993–94)

- 1997 – 1999 Republic of the Congo Civil War (1997–1999)

- 2002 – 2003 2002–2003 conflict in the Pool Department

- 2016 – 2017 Pool War

Congo (Democratic Republic of)

- 1960 – 1965 Congo Crisis

- September 14, 1960 First Mobutu coup d’état

- 1963 – 1965 Kwilu rebellion

- 1963 – 1965 Simba Rebellion

- 1963 – 1966 Kanyarwanda War

- November 25, 1965 Second Mobutu coup d’état

- 1960 – 1962 South Kasai‘s secession

- August – September 1960 Invasion of South Kasai

- September – October 1962 Coup d’état of South Kasai

- 1963 – ongoing Katanga insurgency

- 1966 – 1967 Stanleyville mutinies

- 1977 Shaba I

- 1978 Shaba II

- 1987 — ongoing Lord’s Resistance Army insurgency

- September — October 1991 1991 Zaire unrest

- November 13, 1996 — ongoing Allied Democratic Forces insurgency

- 1996 – 1997 First Congo War

- October 1996 – May 1997 Massacres of Hutus during the First Congo War

- April 9, 1997 Capture of Lubumbashi

- March 13 – 15, 1997 Battle of Kinsangani (1997)

- 1998 – 2003 Second Congo War

- August 4 – 30, 1998 Operation Kitona

- June 5 – 10, 2000 Six-Day War (2000)

Congo (Democratic Republic of)(Continued)

- October 2002 – January 2003 Effacer le tableau

- 1999 – ongoing Ituri Conflict

- 2004 – ongoing Kivu Conflict

- 26 October 2008 – 23 March 2009 2008 Nord-Kivu campaign

- 20 January 2009 – 27 February 2009 2009 Eastern Congo offensive

- 4 April 2012 – 7 November 2013 M23 rebellion

- June 30 – August 10, 2014 2014 North Kivu offensive

- June 1, 2017 – December 26, 2017 2017 CNPSC offensive

- March 27, 2022 – present M23 offensive (2022–present)

- June 11, 2004 2004 Democratic Republic of the Congo coup attempt

- 2009 Dongo conflict

- February 27, 2011 2011 Democratic Republic of the Congo coup attempt

- 2013 – 2018 Batwa-Luba clashes

- December 30, 2013 December 2013 Kinshasa attacks

- 2016 – 2019 Kamwina Nsapu rebellion

- February 8, 2022 2022 Democratic Republic of the Congo coup d’état allegations

- 2022 – present Western DR Congo clashes

- May 19, 2024 2024 Democratic Republic of the Congo coup attempt

Equatorial Guinea/ Gabon

Equatorial Guinea

3–18 August 1979 1979 Equatorial Guinea coup d’état

7 March 2004 2004 Equatorial Guinea coup attempt

December 2017 2017 Equatorial Guinea coup attempt

Gabon

February 17 – 19, 1964 1964 Gabonese coup d’état

January 7, 2019 2019 Gabonese coup attempt

August 30, 2023 2023 Gabonese coup d’état

São Tomé and Príncipe

- February 3, 1953 Batepá Massacre

- March 8, 1988 1988 São Tomé and Príncipe coup attempt

- August 15 – 22, 1995 1995 São Tomé and Príncipe coup attempt

- July 16 – 23, 2003 2003 São Tomé and Príncipe coup attempt

- November 24 – 25, 2022 2022 São Tomé and Príncipe coup attempt

Horn of Africa

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia

- 1973 – ongoing Oromo conflict

- 2018 – present OLA insurgency

- 18 March 2021 – 18 April 2021 2021 Ataye clashes

- 29 March – 19 April 2022 2022 North Shewa clashes

- 23 – 28 October 2019 October 2019 Ethiopian clashes

- 30 June – 2 July 2020 Hachalu Hundessa riots

- 1992 – 2018 Insurgency in Ogaden

- 2007 – 2008 2007–2008 Ethiopian crackdown in Ogaden

- 1994 – present Ethnic violence in Konso

- 1994 – present Ethnic violence against Amaro Koore

- 1998 – 2018 Eritrean–Ethiopian border conflict

- 1998 – 2000 Eritrean–Ethiopian War

- 6 May – 17 June 1998 1998 Eritrean offensive into Ethiopia

- February 1999 February 1999 Eritrean–Ethiopian aerial clashes

- May 29, 2000 Operation Aider

- 2010 2010 Eritrean–Ethiopian border skirmish

- 2016 Battle of Tsorona

- Early to mid 2000s – present Gambela conflict

- 2002 – ongoing Operation Enduring Freedom – Horn of Africa

- 2016 – 2018 Oromo–Somali clashes

- 2018 – present Ethiopian civil conflict (2018–present)

- 22 June 2019 Amhara Region coup attempt

- 2019 – 2022 Benishangul-Gumuz conflict

- 2020 – present Afar–Somali clashes

- 2020 – 2022 Tigray War

- 3 – 4 November 2020 Northern Command attacks (Ethiopia)

- 9 – 11 November 2020 Battle of Humera

- 17 – 28 November 2020 Mekelle offensive

- 11 June 2021 – 6 July 2021 Operation Alula

- 31 October – 1 December 2021 TDF–OLA joint offensive

- 26 November – 23 December 2021 ENDF National Unity Offensive

- 14 – 18 October 2022 Battle of Shire (2022)

- 2020 – 2022 Al-Fashaga conflict

- 2022 2022 al-Shabaab invasion of Ethiopia

- 2023 – present War in Amhara

Federal Republic of Somalia

- 1991 – ongoing Somali Civil War

- 5 December 1992 – 4 May 1993 Unified Task Force

- December 1992 – May 19 Operation Deliverance

- 26 March 1993 – 28 March 1995 United Nations Operation in Somalia II

- 5 June 1993 June 1993 attack on Pakistani military in Somalia

- 2 July 1993 Battle of Checkpoint Pasta

- 12 July 1993 Bloody Monday raid

- 22 August 1993 – 13 October 1993 Operation Gothic Serpent

- 3–4 October 1993 Battle of Mogadishu (1993)

- 1998 – ongoing Puntland-Somaliland dispute

- 15 October 2007 Battle of Las Anod (2007)

- 8 January 2018 Battle of Tukaraq

- 4 June – 20 December 2006 2006 Islamic Courts Union offensive

- 7 May – 11 July 2006 Battle of Mogadishu (2006)

- 20 December 2006 – 30 January 2009 Somalia War (2006–2009)

- 20–26 December 2006 Battle of Baidoa

- 23–25 December 2006 Battle of Bandiradley

- 24–25 December 2006 Battle of Beledweyne (2006)

- 27 December 2006 Battle of Jowhar

- 28 December 2006 Fall of Mogadishu

- 31 December 2006 – 1 January 2007 Battle of Jilib

- 1 January 2007 Fall of Kismayo

- 5 – 12 January 2007 Battle of Ras Kamboni

- 21 March – 26 April 2007 Battle of Mogadishu (March–April 2007)

- 8–16 November 2007 Battle of Mogadishu (November 2007)

- 19–20 April 2008 Battle of Mogadishu (2008)

- 31 May – 3 June 2007 Battle of Bargal (2007)

- 1–26 July 2008 Battle of Beledweyne (2008)

- 8 July 2008 – 26 January 2009 Siege of Baidoa

- 20–22 August 2008 Battle of Kismayo (2008)

- 2000 – ongoing Piracy off the coast of Somalia

- 18 March 2006 Action of 18 March 2006

- 29 October 2007 Dai Hong Dan incident

- 8 December 2008 – ongoing Operation Atalanta

- 16 September 2008 Carré d’As IV incident

- 9 April 2009 April 2009 raid off Somalia

- 17 August 2009 – ongoing Operation Ocean Shield

Federal Republic of Somalia

- 30 March 2010 Action of 30 March 2010

- 18–21 January 2011 MV Beluga Nomination incident

- 6 May 2010 MV Moscow University hijacking

- 12 January 2012 Attack on Spanish oiler Patiño

- 31 January 2009 – ongoing Somali Civil War (2009–present)

- 22 February 2009 2009 African Union base bombings in Mogadishu

- 24–25 February 2009 Battle of South Mogadishu

- 7 May – 1 October 2009 Battle of Mogadishu (2009)

- 11 May – 1 October 2009 Battle for Central Somalia (2009)

- 5 June 2009 Battle of Wabho

- 18 June 2009 2009 Beledweyne bombing

- 1–7 October 2009 Battle of Kismayo (2009)

- 10–14 January 2010 Battle of Beledweyne (2010)

- May–July 2010 Ayn clashes

- 1 May 2010 Mogadishu bombings

- 20 July 2010 2010 Kenya–Al-Shabaab border clash

- 8 August – 17 October 2010 Galgala campaign

- 23 August 2010 – 6 August 2011 Battle of Mogadishu (2010–2011)

- 27 April 2011 Battle of Gedo

- 4 October 2011 Mogadishu bombing

- 16 October 2011 – June 2012 Operation Linda Nchi

- 28 September – 1 October 2012 Battle of Kismayo (2012)

- 11 January 2013 Bulo Marer hostage rescue attempt

- 2001 – 2021 War on Terrorism

- 7 October 2002 – ongoing Operation Enduring Freedom – Horn of Africa

- 3 March 2008 Dobley airstrike

- 1 May 2008 Dhusamareb airstrike

- 8–12 April 2009 Maersk Alabama hijacking

- 14 September 2009 2009 Baraawe raid

- 25 January 2012 Rescue of Jessica Buchanan and Poul Hagen Thisted

- 2023 – present Las Anod conflict (2023–present)

Djibouti/ State of Eritrea

Djibouti

- 1991 – 1994 Djiboutian Civil War

- 1994 – present FRUD insurgency

- 2008 Djiboutian–Eritrean border conflict

- 1995 – 2018 Second Afar insurgency

- 1995 Hanish Islands conflict

- 1998 – 2018 Eritrean–Ethiopian border conflict

- 1998 – 2000 Eritrean–Ethiopian War

- 6 May – 17 June 1998 1998 Eritrean offensive into Ethiopia

- February 1999 February 1999 Eritrean–Ethiopian aerial clashes

- May 29, 2000 Operation Aider

- 2010 2010 Eritrean–Ethiopian border skirmish

- 2016 Battle of Tsorona

- 2008 Djiboutian–Eritrean border conflict

- 21 January 2013 2013 Eritrean Army mutiny

- 2020 – 2022 Tigray War

Indian Ocean Islands

Comoros

- May 13, 1978 1978 Comorian coup d’état

- September 28 – October 3, 1995 Operation Azalee

- April 30, 1999 1999 Comorian coup d’état

- March 25, 2008 Invasion of Anjouan

Madagascar

- 1883–1885 First Madagascar expedition

- 1894–1895 Second Madagascar expedition

- 1942 Battle of Madagascar (World War II)

- 1947 – 1949 Malagasy Uprising

- 26 January – 7 November 2009 2009 Malagasy political crisis

- 2009 2009 Camp Capsat mutiny

Mauritius/ Seychelle

Mauritius

- August 20, 1810 – August 27, 1810 Battle of Grand Port

- 4–5 June 1977 1977 Seychelles coup d’état

- 25 November 1981 1981 Seychelles coup attempt

Southern Africa

South Africa

1950 Witzieshoek revolt

21 March 1960 Sharpeville Massacre

16 June 1976 Soweto Uprising

3 September 1984 Vaal uprising

1986 – 1987 Ciskei-Transkei conflict

30 December 1987 1987 Transkei coup d’état

4 March 1990 1990 Ciskei coup d’état

5 April 1990 1990 Venda coup d’état

9 August 1991 Battle of Ventersdorp

7 September 1992 Bisho massacre

25 July 1993 Saint James Church massacre

30 December 1993 Heidelberg Tavern massacre

1994 1994 Bophuthatswana crisis

28 March 1994 Shell House massacre

1966 – 1990 South African Border War

Angola/ Malawi

- 1961 – 1974 Angolan War of Independence

- 1966 – 1990 South African Border War

- 4 May 1978 Battle of Cassinga

- 1975 – present Cabinda War

- 1975 – 2002 Angolan Civil War

- 27 May 1977 1977 Angolan coup attempt

- 14 August 1987 – 23 March 1988 Battle of Cuito Cuanavale

- August 3, 1914 – November 1918 World War I

- 3 March 1959 – 16 June 1960 Nyasaland emergency of 1959

- 3 – 5 March 1959 Operation Sunrise

- 1992 – 1993 Operation Bwezani

Mozambique/ Namibia

July 28, 1914 – November 11, 1918 World War I

1964 – 1974 Mozambican War of Independence

1964 – 1979 Rhodesian Bush War

1977 – 1992 Mozambican Civil War

2013 – 2021 RENAMO insurgency (2013–2021)

2017 – ongoing Insurgency in Cabo Delgado

- 1904–1907 Herero Genocide

- July 28, 1914 – November 11, 1918 World War I

- September 15, 1914 – February 4, 1915 Maritz Rebellion

- August 26, 1966 – March 21, 1990 South African Border War

- 1994 – 1999 Caprivi conflict

Lesoto

- 1880–1881 Basotho Gun War

- 30 January 1970 1970 Lesotho coup d’état

- 1974 – 1990 BCP Insurgency

- 20 January 1986 1986 Lesotho coup d’état

- 30 April 1991 1991 Lesotho coup d’état

- 17 August 1994 1994 Lesotho coup d’état

- 22 September 1998 – May 1999 South African intervention in Lesotho

- 30 August 2014 2014 Lesotho political crisis

West Africa

Benin

- 1724–1727 Abomey (Dahomey) conquests

- 1726–1730 First Oyo-Dahomey War

- 1738–1748 Oyo Conquest of Dahomey

- 1764 Second Ashanti-Akim War

- 1768 Yoruba-Ashanti War

- 1851 First Dahomean-Abeokuta War

- 1864 Second Dahomean-Abeokuta War

- 1889–1894 France conquers Dahomey

- October 28, 1963 1963 Dahomeyan coup d’état

- October 26, 1972 1972 Dahomeyan coup d’état

- January 17, 1977 1977 Benin coup attempt

Côte d'Ivoire

- 1883–1898 Mandingo Wars

- December 24, 1999 1999 Ivorian coup d’état

- January 7 – 8, 2001 2001 Ivorian coup attempt

- 2002 – 2007 First Ivorian Civil War

- September 19, 2002 2002 Ivorian coup attempt

- September 22, 2002 – January 21, 2015 Opération Licorne

- 2004 2004 French–Ivorian clashes

- 2010 – 2011 Second Ivorian Civil War

- June 12, 2012 2012 Ivorian coup attempt

- May 6 – 16, 2017 2017 Ivory Coast mutinies

Ghana

- 1620–1654 Dutch–Portuguese War

- 1664–1665 Anglo-Dutch Wars

- 1823–1831 Anglo-Ashanti wars

- 1900 War of the Golden Stool

- February 28, 1948 1948 Accra Riots

- February 24, 1966 1966 Ghanaian coup d’état

- April 17, 1967 Operation Guitar Boy

- June 4, 1979 June 4th revolution in Ghana

- December 31, 1981 1981 Ghanaian coup d’état

- 1994 – 2015 Konkomba–Nanumba conflict

- 2002 Yendi conflict

- 2019 – Present Gonja-Mamprusi conflict

- 2020 – Present Western Togoland Rebellion

Guinea

- 22 November 1970 Operation Green Sea

- 3 April 1984 1984 Guinean coup d’état

- February 2 – 3, 1996 1996 Guinean coup attempt

- 2000 – 2001 RFDG Insurgency

- 2013 2013 Guinea clashes

- 5 September 2021 2021 Guinean coup d’état

Gambia

- 30 July – 4 August 1981 1981 Gambian coup attempt

- 22 July 1994 1994 Gambian coup d’état

- 30 December 2014 2014 Gambian coup attempt

- 9 December 2016 – 21 January 2017 2016–2017 Gambian constitutional crisis

- 2017 – present ECOWAS military intervention in the Gambia

- 20 December 2022 2022 Gambian coup attempt

Liberia

- October 1871 1871 Liberian coup d’état

- April 12, 1980 1980 Liberian coup d’état

- November 12, 1985 1985 Liberian coup attempt

- September 15, 1994 1994 Liberian coup attempt

- 1989 – 1996 First Liberian Civil War

- 1998 1998 Monrovia clashes

- 1999 – 2003 Second Liberian Civil War

Guinea Bissau

23 January 1963 – 10 September 1974 Guinea-Bissau War of Independence

14 November 1980 1980 Guinea-Bissau coup d’état

1998 – 1999 Guinea-Bissau Civil War

7 June 1998 1998 Guinea-Bissau coup attempt

14 September 2003 2003 Guinea-Bissau coup d’état

26 December 2011 2011 Guinea-Bissau coup attempt

12 April 2012 2012 Guinea-Bissau coup d’état

1 February 2022 2022 Guinea-Bissau coup attempt

30 November 2023 – 1 December 2023 2023 Guinea-Bissau coup attempt

Senegal

- 1549 Battle of Danki

- 1644-1677 Char Bouba war

- 1860-1886 Franco-Cayor Wars

- 1880-1899 Franco-Wolof Wars

- 1860-1920 French Conquest of Casamance

- 1886-1887 Uprising of Mahmadu Lamine

- 1982 – ongoing Casamance conflict

- 1989 – 1991 Mauritania–Senegal Border War

- 2007 – ongoing Operation Juniper Shield

Sierra Leone

- February 7, 1813 Action

- March 21 – 23, 1967 1967 Sierra Leonean coups d’état

- April 18, 1968 Sergeant’s Coup

- 1982 Ndogboyosoi War

- 1991 – 2002 Sierra Leone Civil War

- April 29, 1992 1992 Sierra Leonean coup d’état

- November 26 – 28, 2023 2023 Sierra Leone coup attempt

Burkina Faso

- 3 January 1966 1966 Upper Voltan coup d’état

- 8 February 1974 1974 Upper Voltan coup d’état

- 25 November 1980 1980 Upper Voltan coup d’état

- 7 November 1982 1982 Upper Voltan coup d’état

- 28 February 1983 1983 Upper Voltan coup attempt

- 4 August 1983 1983 Upper Voltan coup d’état

- 1985 Agacher Strip War

- 15 October 1987 1987 Burkina Faso coup d’état

- 18 September 1989 1989 Burkina Faso coup attempt

- 2007 – ongoing Operation Juniper Shield

- 2011 – present Islamist insurgency in the Sahel

- August 1, 2014 — November 9, 2022 Operation Barkhane

- 2015 – present Jihadist insurgency in Burkina Faso

- 2 March 2018 2018 Ouagadougou attacks

- 16 – 23 September 2015 2015 Burkina Faso coup attempt

- 8 October 2016 2016 Burkina Faso coup attempt

- 23 – 24 January 2022 January 2022 Burkina Faso coup d’état

- 30 September 2022 September 2022 Burkina Faso coup d’état

- 26 September 2023 2023 Burkina Faso coup attempt

Mauritania

- June 17, 1970 – ongoing Western Sahara conflict

- 10 July 1978 1978 Mauritanian coup d’état

- 6 April 1979 1979 Mauritanian coup d’état

- 4 January 1980 1980 Mauritanian coup d’état

- 16 March 1981 1981 Mauritanian coup attempt

- 12 December 1984 1984 Mauritanian coup d’état

- 1989 – 1991 Mauritania–Senegal Border War

- 2002 – ongoing Insurgency in the Maghreb (2002–present)

- 6 February 2007 – ongoing Operation Juniper Shield

- August 1, 2014 — November 9, 2022 Operation Barkhane

- 8 – 9 June 2003 2003 Mauritanian coup attempt

- 3 August 2005 2005 Mauritanian coup d’état

- 6 August 2008 2008 Mauritanian coup d’état

Nigeria

- 1967 – 1970 Nigerian Civil War

- July 2 – 12, 1967 Operation UNICORD

- August 9 – September 20, 1967 Midwest Invasion of 1967

- 12 September – 4 October 1967 Fall of Enugu

- October 4 – 12, 1967 First Invasion of Onitsha

- October 17 – 19, 1967 Operation Tiger Claw

- January 2 – March 20, 1968 Second Invasion of Onitsha

- 31 March 1968 Abagana Ambush

- March 8 – May 24, 1968 Invasion of Port Harcourt

- 2 September – 15 October 1968 Operation OAU

- 15 – 29 November 1968 Operation Hiroshima

- October 15, 1968 – April 25, 1969 Siege of Owerri

- March 27 – April 22, 1969 Operation Leopard (1969)

- December 20 – 24, 1969 Invasion of Umuahia

- 15 – 16 January 1966 1966 Nigerian coup d’état

- 28 July – 1 August 1966 1966 Nigerian counter-coup

- January 7 – 12, 1970 Operation Tail-Wind

- July 29, 1975 1975 Nigerian coup d’état

- February 13, 1976 1976 Nigerian coup attempt

- April 1983 Chadian–Nigerian War

- 31 December 1983 1983 Nigerian coup d’état

- August 27, 1985 1985 Nigerian coup d’état

- April 22, 1990 1990 Nigerian coup attempt

- November 17, 1993 1993 Nigerian coup d’état

Nigeria (Continued)

- 1997 – 2003 Warri Crisis

- 1998 – present Communal conflicts in Nigeria

- 1953 – present Religious violence in Nigeria

- 1998 – present Herder–farmer conflicts in Nigeria

- 2011 – present Nigerian bandit conflict

- 2003 – present Conflict in the Niger Delta

- 2016 – present 2016 Niger Delta conflict

- 2021 – present Insurgency in Southeastern Nigeria

- 16 May 2023 2023 Anambra ambush

- 14 September 2001 – 30 August 2021 War on terror

- 2007 – ongoing Operation Juniper Shield

- 2009 – present Boko Haram insurgency

- 26 – 29 July 2009 2009 Boko Haram uprising

- 13 – 14 May 2014 Chibok ambush

- 23 January – 24 December 2015 2015 West African offensive

- November 2018 – February 2020 Chad Basin campaign (2018–2020)

- 15 February 2011 – present Islamist insurgency in the Sahel

- March 8, 2014 2014 Enugu Government House attack

- June 15, 2014 2014 Enugu State Broadcasting Service attack

Mali

- 1962 – 1964 Tuareg rebellion (1962–64)

- 1985 Agacher Strip War

- 1990 – 1995 Tuareg rebellion (1990–95)

- 2002 – ongoing Insurgency in the Maghreb (2002–present)

- 6 February 2007 – ongoing Operation Juniper Shield

- 2009 – present Boko Haram insurgency

- 23 January – 24 December 2015 2015 West African offensive

- November 2018 – February 2020 Chad Basin campaign (2018–2020)

- 2011 – present Islamist insurgency in the Sahel

- January 16, 2012 – present Mali War

- January 16, 2012 – April 6, 2012 2012 Tuareg rebellion

- January 18, 2012 — March 11, 2012 Battle of Tessalit

- January 17 — 25, 2012 Battle of Aguelhok

- February 7 — 8, 2012 Battle of Tinzaouaten (2012)

- March 21, 2012 — April 8, 2012 2012 Malian coup d’état

- June 27, 2012 — ongoing Azawad conflict

- June 26 — 27, 2012 Battle of Gao

- November 16 — 20, 2012 Second Battle of Ménaka

- February 22 — 23, 2013 Battle of Khalil

- March 29 — 30, 2013 Battle of In Arab

- January 11, 2013 — 15 July 2014 Operation Serval

- August 1, 2014 — November 9, 2022 Operation Barkhane

- August 18, 2020 2020 Malian coup d’état

- May 24, 2021 2021 Malian coup d’état

- 2006 2006 Tuareg rebellion

- 2007 – 2009 Tuareg rebellion (2007–2009)

Niger/Togo

Niger

- 1516–1517 Songhai Civil War

- 1916–1917 Kaocen Revolt

- 15 April 1974 1974 Nigerien coup d’état

- 1990 – 1995 Tuareg rebellion (1990–95)

- 27 January 1996 1996 Nigerien coup d’état

- 9 April 1999 1999 Nigerien coup d’état

- 2007 – 2009 Tuareg rebellion (2007–09)

- * 2002 – ongoing Insurgency in the Maghreb (2002–present)

- 2007 – ongoing Operation Juniper Shield

- 2011 – present Islamist insurgency in the Sahel

- August 1, 2014 — November 9, 2022 Operation Barkhane

- 2015 – present Jihadist insurgency in Niger

- 4 October 2017 Tongo Tongo ambush

- 2009 – present Boko Haram insurgency

- 23 January – 24 December 2015 2015 West African offensive

- November 2018 – February 2020 Chad Basin campaign (2018–2020)

- 18 February 2010 2010 Nigerien coup d’état

- 12 – 13 July 2011 2011 Nigerien coup attempt

- 31 March 2021 2021 Nigerien coup attempt

- 26 – 28 July 2023 2023 Nigerien coup d’état

- 29 July 2023 – 24 February 2024 Nigerien crisis (2023–2024)

13 January 1963 1963 Togolese coup d’état

13 January 1967 1967 Togolese coup d’état

23 September 1986 1986 Togolese coup attempt

February 5 – 25, 2005 2005 Togolese coup d’état

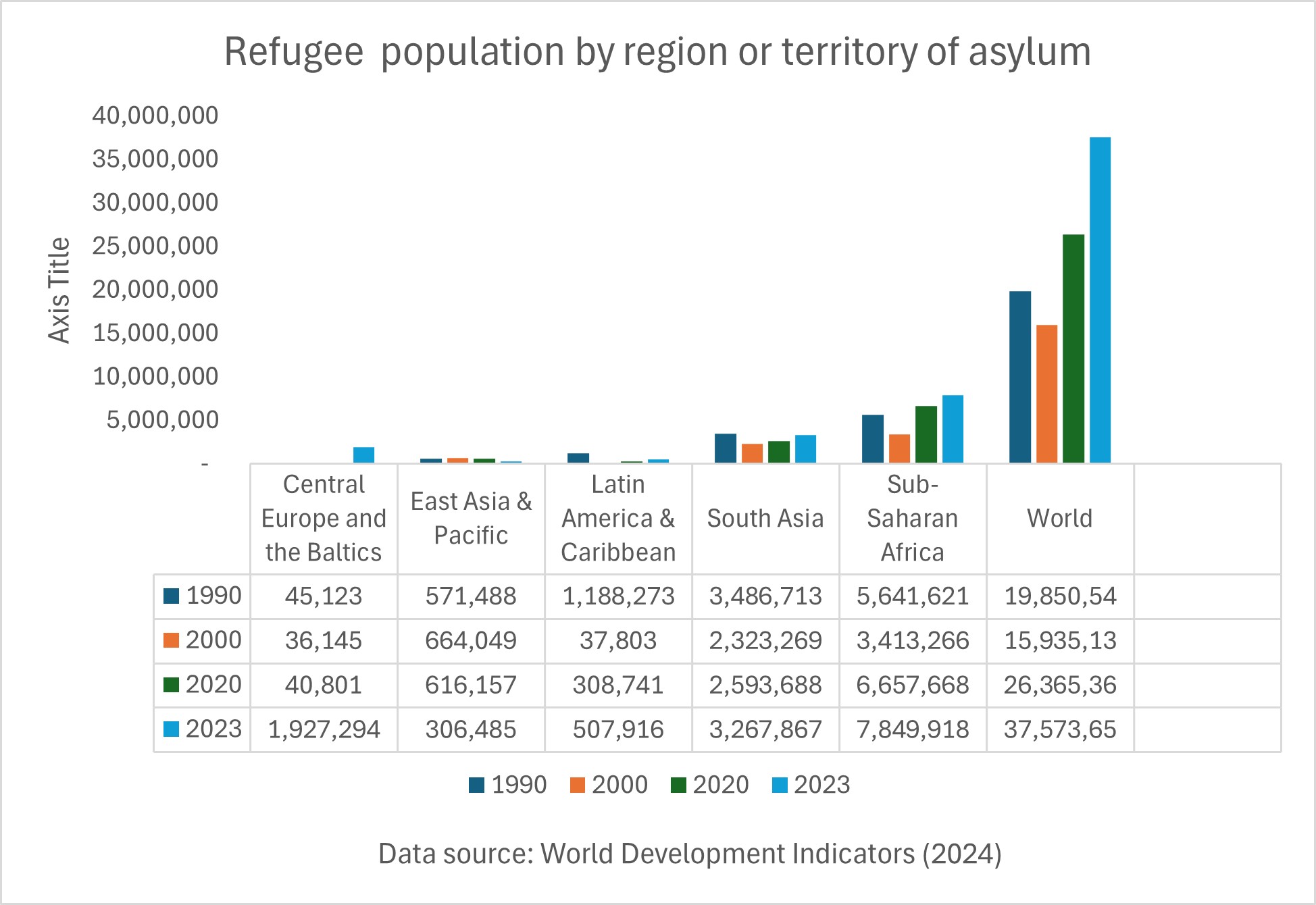

Highest Refugee Population in Developing World

Compassionate Refugee Camps in the Developing World

Sub-Saharan Africa remains a region marked by the highest number of displaced individuals worldwide, carrying a significant burden of the global refugee population. The region confronts severe challenges that are deeply rooted in its economic realities, complex dynamics of displacement, and uneven capabilities for humanitarian response, presenting a stark contrast to the situations encountered in other developing regions.

Economic Indicators sixty years post independence: A Global Perspective

Lowest GDP per capita, constant prices (PPP: 2017 international dollar

Lowest contribution to global Gross Domestic Product of the world total, 1980 to 2029

Lowest total trade and share in the world, 1970 to 2023

Lowest intra-trade in developing region, 1995-2023

Sustained trade deficit than any other developing region in 43 years, 1980 to 2023

Lowest inward and share of foreign direct investment in the world, 1990 to 2023

Lowest global GDP share from 1980 to 2024

Lowest average percent change in GDP, lowest average investment as share of GDP, and lowest average national saving as percent of GDP

Highest share of external debt as percent of GDP, from 1980 to 2024

GLOBAL EFFORTS TO DEVELOP SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA,1960 - 2025

Official Development Assistance and External Debt in Sub-Saharan Africa

Official Development Assistance from All Donors

Official Development Aid from the United States

Total Estimated ODA and Total External Debt

OTHER GLOBAL DEVELOPMENT INITIATIVES IN SUBSAHARAN AFRICA

UN Declaration on the Critical Economic Situation in Africa

United Nations Programme of Action for African Economic Recovery and Development

UNited Nations New Agenda for Development in Africa

Africa-Europe Summit Under the Aegis of the OAU and EU

Why Sub-Saharan Africa Must Unite?

Sub-Saharan Africa stands at a crucial juncture where we must unite to eradicate the cycle of poverty, promote self-sufficiency, and ensure peace and security across our nations through determined collective action. Now is the time for solidarity as we confront historical and contemporary challenges, unlocking the immense potential of our region. Together, we can harness our abundant natural and human resources to forge a future filled with dignity, prosperity, and true independence. Let us seize this opportunity to pursue a common vision for Sub-Saharan Africa, fostering an enduring legacy of growth and resilience. Let us unite and realize our long-held collective aspiration for a United Sub-Saharan Africa. Here are some key reasons:

Overcoming Colonial Legacies

Economic Fragmentation: Economic Fragmentation poses profound challenges as the persistence of numerous small nation-states in Sub-Saharan Africa significantly impedes their capacity to fully exploit the advantages associated with economies of scale. Many of these countries find themselves at a disadvantage in the global marketplace, struggling to compete due to their limited size and fragmented markets. Nevertheless, the prospect of a unified Sub-Saharan Africa presents an opportunity for the establishment of a cohesive and robust market that could enhance economic stability while fostering growth and innovation. By consolidating resources, skills, and infrastructure, a united continent could leverage its collective strengths and emerge as a formidable entity in international trade and development.

Economic Prosperity

Regional Trade: A unified Sub-Saharan Africa offers a tremendous opportunity to invigorate intra-African trade, which, despite considerable efforts towards economic integration, remains strikingly low in comparison to other global regions, underscoring the urgent need for collective action and collaboration to unlock this potential for growth and prosperity.

Industrialization: Unity is essential for pooling resources that drive industrial development, significantly reducing our reliance on raw material exports while simultaneously boosting the production of value-added goods, which is vital for sustainable economic growth.

Global Negotiation Power: A united front in global negotiations empowers us to secure stronger positions in international trade and politics, paving the way for equitable trade agreements and enhanced access to vital global markets.

Political Stability

Conflict Resolution: A federal system presents a unique opportunity to empower Sub-Saharan Africa with a robust army of Sub-Saharan Africa and other means of conflict resolution, effectively creating a powerful platform for mediation and negotiation that can significantly diminish or even eradicate both interstate and intrastate conflicts and disputes.

Shared Security: Shared security is not just important; it is vital as our collective commitment empowers us to confront and overcome the urgent transnational challenges of terrorism, organized crime, and resource exploitation that threaten the fabric of our global community.

Collective Self-Reliance

Reduce Dependency: Unity will reduce or eliminate our dependence on external aid and inspires us to embrace our potential for self-sufficiency by wholeheartedly supporting innovative local solutions and fostering sustainable development practices that enable communities to thrive independently as they address their unique challenges and seize promising opportunities for growth.

Resource management: A unified strategy for resource management is essential to safeguard against external exploitation while empowering Africa’s rich natural and human resources to uplift every African. Together, we can forge a sustainable future where local communities thrive and take ownership of their resources, fostering economic independence and resilience across the continent, and inspiring a movement of collective self-reliance that benefits all.

Addressing Common Challenges

Health Crises: A unified healthcare policy is crucial for effectively tackling health crises by improving our ability to manage pandemics ensuring fair access to essential medicines and strengthening public health systems. By encouraging collaboration among nations and healthcare providers we can build a resilient framework that responds swiftly to health threats while emphasizing preventive measures and health education for healthier populations and robust healthcare infrastructures.

Education and Innovation: Collaboration in education and innovation is crucial for shaping a brighter future for Africa’s youth, who are the continent’s emerging leaders and innovators. By building strong partnerships among educational institutions, research organizations, and industry stakeholders, we can create a dynamic environment that enhances learning and equips young minds with essential skills to tackle global challenges. This collective effort will empower them to contribute effectively to their communities and foster sustainable development across Africa, unlocking the full potential of the continent’s youth.

Demographic Dividend

Youth empowerment:Youth empowermentis crucial for Sub-Saharan Africa, which boasts the youngest population globally. This unique demographic presents an incredible opportunity to foster unity, driving significant advancements in education, enhancing employment opportunities, and sparking innovative solutions tailored to the needs of this vibrant youth segment. By recognizing and tapping into this vast potential, we can leverage the region’s demographic advantages, paving the way for a brighter and more sustainable future for everyone.

Fostering Unity: Youth engagement is vital for unity and sustainable development in Sub-Saharan Africa, offering innovative solutions to persistent challenges. By leveraging their creativity, young people can lead initiatives that enhance environmental stewardship, drive economic empowerment, and build social cohesion, creating significant community change. Their advocacy for policies that resonate with their vision bridges generational gaps and fosters collaboration between leaders and citizens. This active involvement in decision-making lays the groundwork for a future where sustainable practices are the standard, ensuring responsible resource management in Africa for generations to come. Investing in youth engagement cultivates resilience and shared prosperity, inspiring all Africans to contribute to a lasting legacy of unity and development.

Pan-African Identity and Pride

Shared Heritage: Unity empowers Africans to boldly reclaim their narrative and shape their destiny on the global stage, showcasing the extraordinary resilience, limitless creativity, and immense potential that define the continent. This collective strength cultivates a vibrant representation of African identity, allowing diverse voices to resonate and be celebrated, while fundamentally transforming the global perception of Africa. By embracing unity, Africans ignite inspiration in a new generation and champion a vision of progress that honors their rich heritage and aspirations, paving the way for a brighter future.

Reclaiming Narrative: Unity empowers Africans to take charge of their destiny and reshape their narrative on the global stage, celebrating the remarkable resilience, vibrant creativity, and vast potential that flourish within the continent. This united strength enhances appreciation for Africa’s invaluable contributions to global culture and underscores its pivotal role in development. By fostering this sense of unity, we craft a more inclusive narrative that honors the richness of African experiences while inspiring pride and collaboration among its people.

Building a Global Leader

Global Influence: Unity holds the transformative power to elevate Sub-Saharan Africa to a vital position in global politics and economics, empowering the region to assert its influence and play an active role in shaping the international landscape that affects its future and that of the world at large. By nurturing collaboration and solidarity among its nations, this unity can forge a compelling voice essential for championing the interests and aspirations of Sub-Saharan Africa on the global stage, inspiring a collective momentum towards sustainable progress and prosperity.

African Renaissance: African Renaissance embodies an inspiring movement where the nations of Sub-Saharan Africa unite in solidarity to become the catalyst for significant global progress, remarkable innovation, and steadfast justice. Through the power of collaboration and shared purpose, this dynamic region is poised to redefine the narrative, ignite transformative change, and pave the way for a fairer and more just world for everyone.

Voices for Unity

An address entitled ” the future of Africa” by DuBois who was at that time approaching 91 years of age and unwell, was given on his behalf by his wife. Among other things he said,

“If Africa unites, it will be because each part, each nation, each tribe gives up a part of the heritage for the good of the whole. That is what union means; that is what Pan Africa-means: When the child is born into the tribe the price of his growing up is giving a part of his freedom to the tribe. This he soon learns or dies. When the tribe becomes a union of tribes, the individual tribe surrenders some part of its freedom to the paramount tribe.”

“We are not interested in the preservation of any of the structures of the colonial state. It is our opinion that it is necessary to destroy, to break, to reduce to ash all aspects of the colonial state in our countries to make everything possible for our people. The problem of the nature of the state created after independence is perhaps the secret of the failure of African independence.”

Deputy Executive Secretary of the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA)

Unity Statistics