Sub-Saharan Africa

- Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is a subregion of the African continent located south of the Sahara. As of 2024, the region contained 48 nation-states, most of which were characterized “ by their low per capita income, high poverty rates, and susceptibility to external shocks” (United Nations, 2019).

- As of December 2024, there remain 44 nations classified as least developed countries (LDCs), with 32 situated in Sub-Saharan Africa. The United Nations designates LDCs as developing nations exhibiting the lowest levels of socioeconomic advancement. These nations face heightened risks of enduring extreme poverty and are often mired in underdevelopment, with over 75 percent of their populations living below the poverty line. Furthermore, according to the UN, LDCs are particularly vulnerable to external economic shocks, natural and manmade disasters, and communicable diseases, necessitating substantial support from the international community. Currently, 32 out of 48 Sub-Saharan African countries find themselves in this challenging predicament, six decades after independence.

- As of December 2024, 32 countries are identified as Land Locked Developing Countries (LLDCs), with 16 located in Sub-Saharan Africa. According to the UN, the lack of sea access, isolation from global markets, and high transit costs severely hinder the socio-economic development of these nations. LLDCs typically incur transport costs over twice those of transit countries and face longer delivery times for imports and exports. Their neighboring transit countries, often also developing, share similar economic difficulties, which results in minimal trade between them. Additionally, these neighbors often struggle with inadequate transport infrastructure, compounding the trade obstacles faced by LLDCs. Overall, the development level in LLDCs is about 20 percent lower than it would be if they were not landlocked. Economically, LLDCs rely heavily on a narrow range of commodities and minerals, experience high unemployment and low productivity, and exhibit a high concentration of trade in a limited number of products.

- The World Bank’s 2024 classification by income reveals that among the 48 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, a significant 22 are categorized as low-income countries, or LICs, characterized by a Gross National Income per capita of less than or equal to US$ 1,145. This classification underscores the economic challenges faced by many nations in the region, highlighting the pressing need for targeted support and sustainable development initiatives to improve living standards and foster growth in these vulnerable economies.

- As of 2023, the total population of Sub-Saharan Africa is estimated to exceed 1.2 billion individuals, characterized by a notably youthful demographic with approximately 60 percent of the population being under the age of 25, highlighting a vibrant future ahead.

- A staggering 71 percent of the workforce in the region is engaged in what is classified as vulnerable employment, indicating a significant challenge for job security and economic stability.

- As of 2023, 43 percent of the population resides in urban areas, reflecting a shift towards city living and its associated opportunities and challenges.

- As of 2023, 57 percent of Sub-Saharan Africa’s population lived in rural areas, where they depended heavily on agriculture as their primary means of livelihood, underscoring the critical role of agriculture in sustaining these communities.

Exploring the Unfulfilled Promises

Sub-Saharan Africa: Sixty Years On

Unraveling the Roots of Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa’s journey to independence was marked by hope and determination. However, six decades later, the region continues to grapple with numerous challenges, including economic disparities, political instability, and social inequalities.

Our mission is to shed light on these issues and foster dialogue for a brighter future.There is no mystery why sub-Saharan Africa stands as the world’s poorest region, with its citizens being among the most impoverished globally, despite the abundance of arable land and natural resources. The critical neglect of agriculture, which has sustained the vast majority of the region’s population since independence in the 1960s, plays a significant role in perpetuating chronic poverty and underdevelopment. Consequently, it is clear why sub-Saharan Africa continues to struggle economically, even with its rich potential in agricultural and natural resources.

In his book “ How Asia Work,” Studwell (2013) writes:

Agricultural development policy, including land policy, is the acid test of a government of a poor country because it measures the extent to which leaders are in touch with the bulk of their population, and the extent to which they are willing to shape up society to produce developmental outcomes. Agricultural development policy tells you how much leaders know and care about the vast majority of their population.

- According to Studwell (2013), “ A massive investment in agriculture in Asia produced two enormously beneficial effects that could not be achieved through other policies. The first effect was the fullest possible use of labor population in rural economies to maximize output; the second effect was both high level of income and social mobility.” Said Studwell. “With most human resources concentrated in agriculture , the sector offers poor countries the most immediate opportunity to increase economic output. East Asia after Second World War was no exception. Even Japan which began its development in the 1870 with a three-quarters rural population, almost half of the workforce was still farm-based at the start of the war.”

- Michael Lipton well put it in these terms: “In early developmental stage, with labor plentiful and the ability to save scarce resources, agriculture is especially promising, because it is the part of the economy in which a given amount of scarce investible resources will be supported by the most human efforts.”

- “In retrospect, the most critical failure appears to have been independent Sub-Saharan Africa’s severe neglect of its own agricultural development, the sector on which the vast majority of its people depend on for their lines of work and their livelihoods,” said Sanford J. Ungar (1985).

- “I was calling on Sub-Saharan African leaderships to go beyond declarations and to go beyond conferences-That is true. Sub-Saharan African countries are not meeting their Maputo declaration of allocating a minimum of 10 percent of their budgets to agriculture, the sector on which the vast majority of their population depend on for their line of work and for their livelihood, they have to double efforts,” said Kanayo F. Nwanze (President of the International Fund for Agricultural Development, June 2014).

- Although most Sub-Saharan Africans live in rural areas and depend on agriculture for their livelihoods, a study in 2015 shows that agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa registered growth, but only where weather conditions were favorable, and that, “The sector was mostly not a chief priority for major government investment.”

The Numbers Behind the Struggle

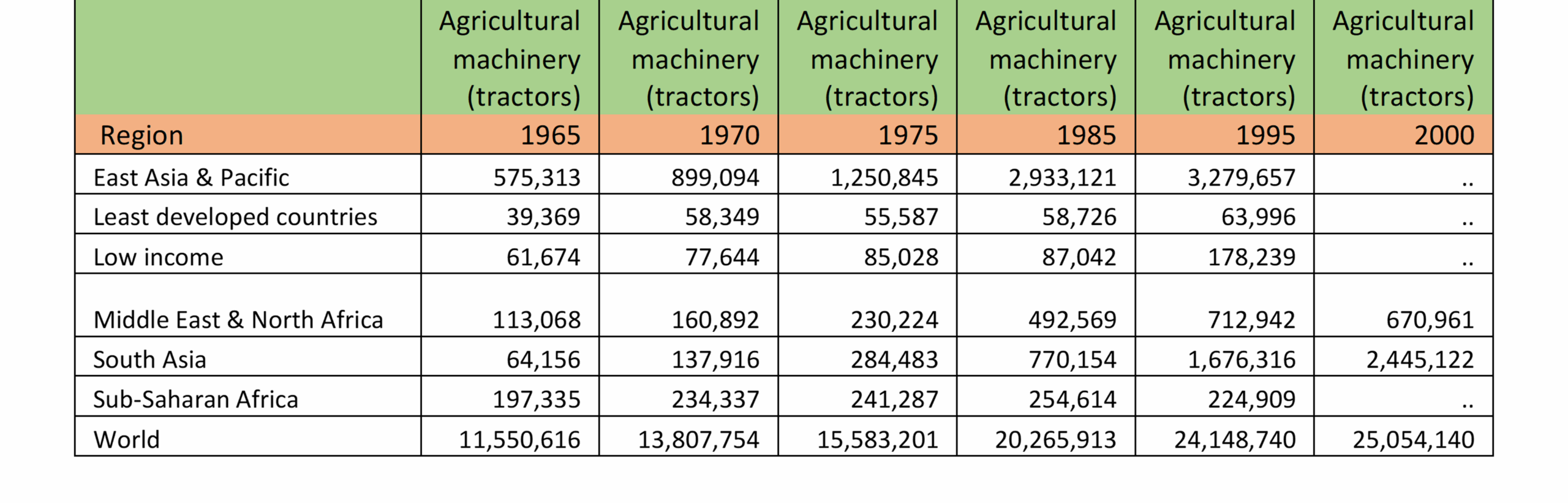

Table 1-6 gives both investment levels in agriculture in terms of agricultural machinery (tractors) and agricultural productivity in terms of cereal yields (kg per hectare) in sub-Saharan Africa and other developing regions, between 1965 and 2000.

Table 1 : Agricultural Machinery (Tractors) in sub-Saharan Africa and other developing regions, 1965-2000

Table 1 gives the number of agricultural machinery(tractors) in sub-Saharan Africa and other developing regions over the period 1965-2000:

The number of tractors in sub-Saharan Africa increased to 254,614 tractors in 2000 from 197,335 tractors in 1965(Compared with the number of tractors in East Asia and the Pacific which increased to 3,279,657 tractors in 2000 from 575,313 tractors in 1965, that in South Asia increased to 2,445,122 tractors in 2000 from 64,156 tractors in 1965) (see table1 on the left).

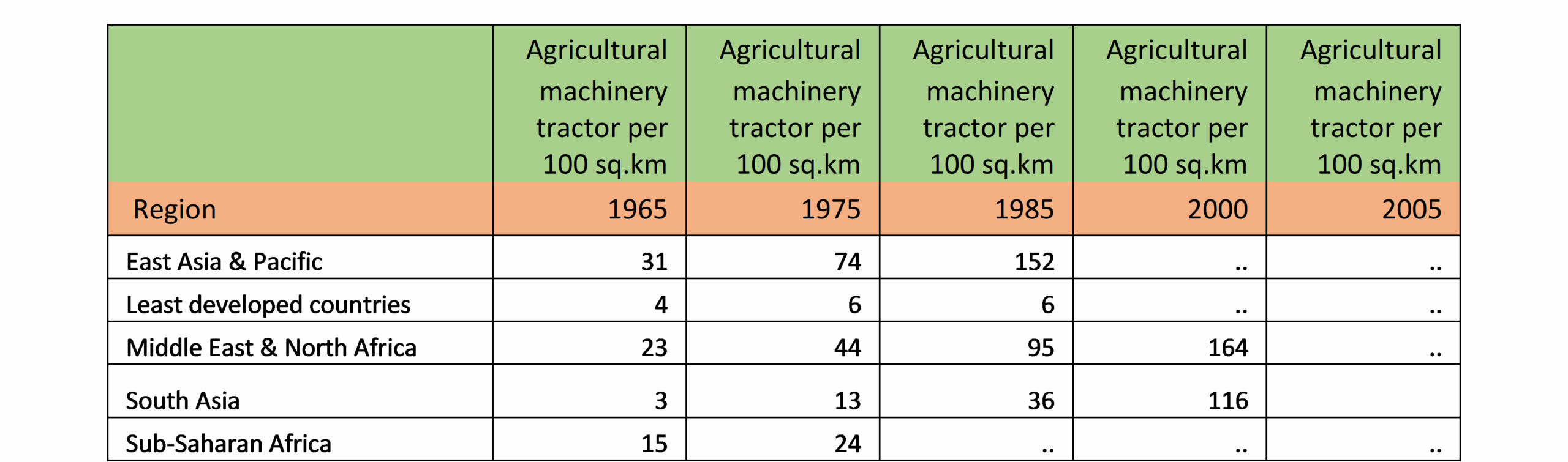

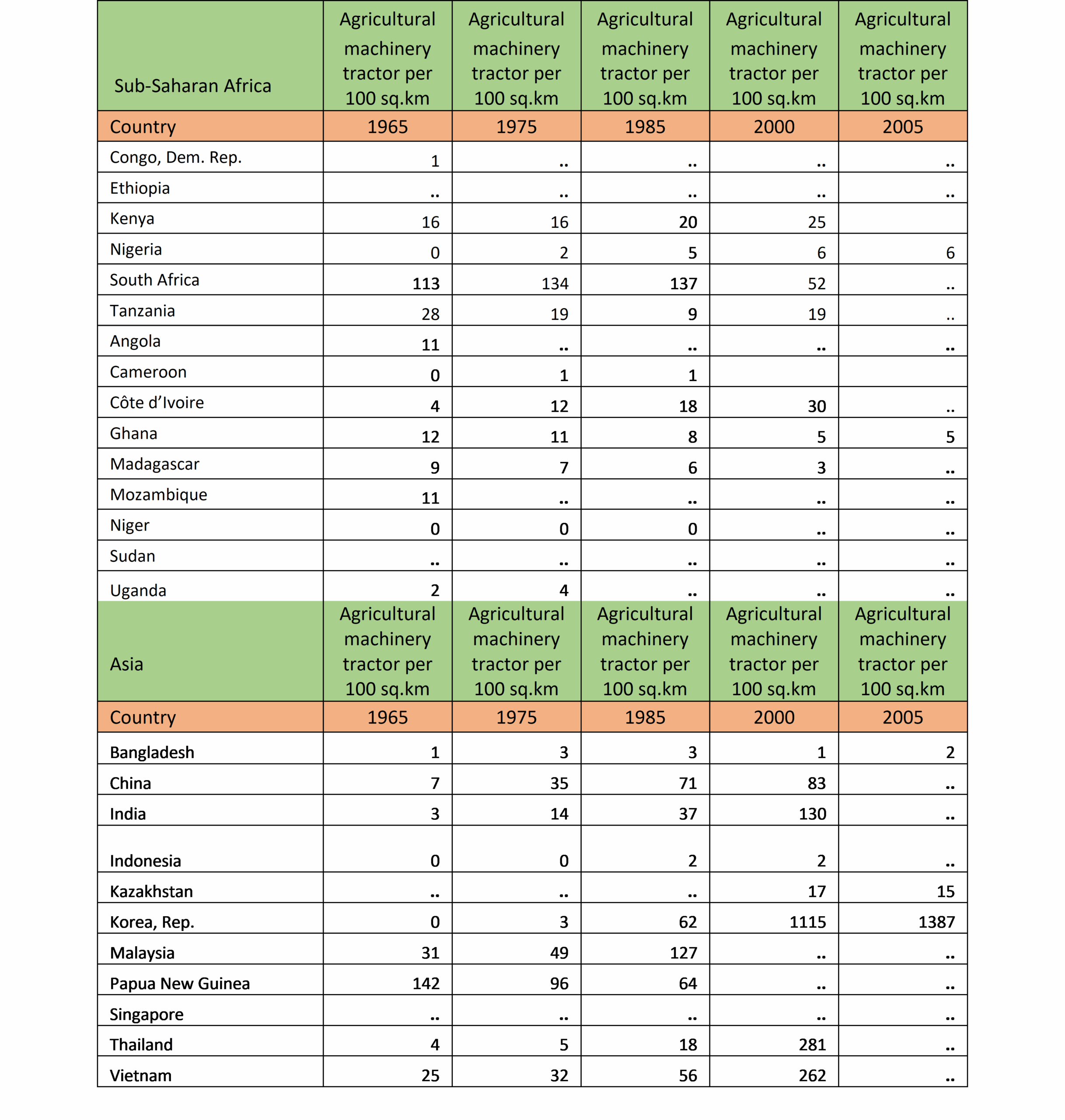

Table 2: Agricultural machinery (Tractors) per 100 sq.km in sub-Saharan Africa and other developing regions, 1965-2005

Table 2 gives the number of agricultural machineries per 100 sq.km by region, between 1965 and 2005:

The number of agricultural machinery (tractors per sq.km) in sub-Saharan Africa increased to 24 tractors per sq.km in 1975 from 15 tractors per sq.km in 1965. Between 1975 and 2005, there was no investment in agricultural machineries in sub-Saharan Africa so the number of tractors per sq.km remained at 24 tractors per sq.km or less, over the period 1975 – 2005 ( Compared with the number of tractors per sq.km in East Asia and the Pacific which increased to 74 in 1975 from 31 tractors per sq.km in 1965. Between 1975 to 1985, the number of tractors per sq.km in East Asia and the Pacific increased to 152 tractors in 1985 from 74 tractors per sq.km in 1975; that in South Asia increased to 116 tractors per sq.km in 2000 from 3 in 1965)(see table 2 on the left)

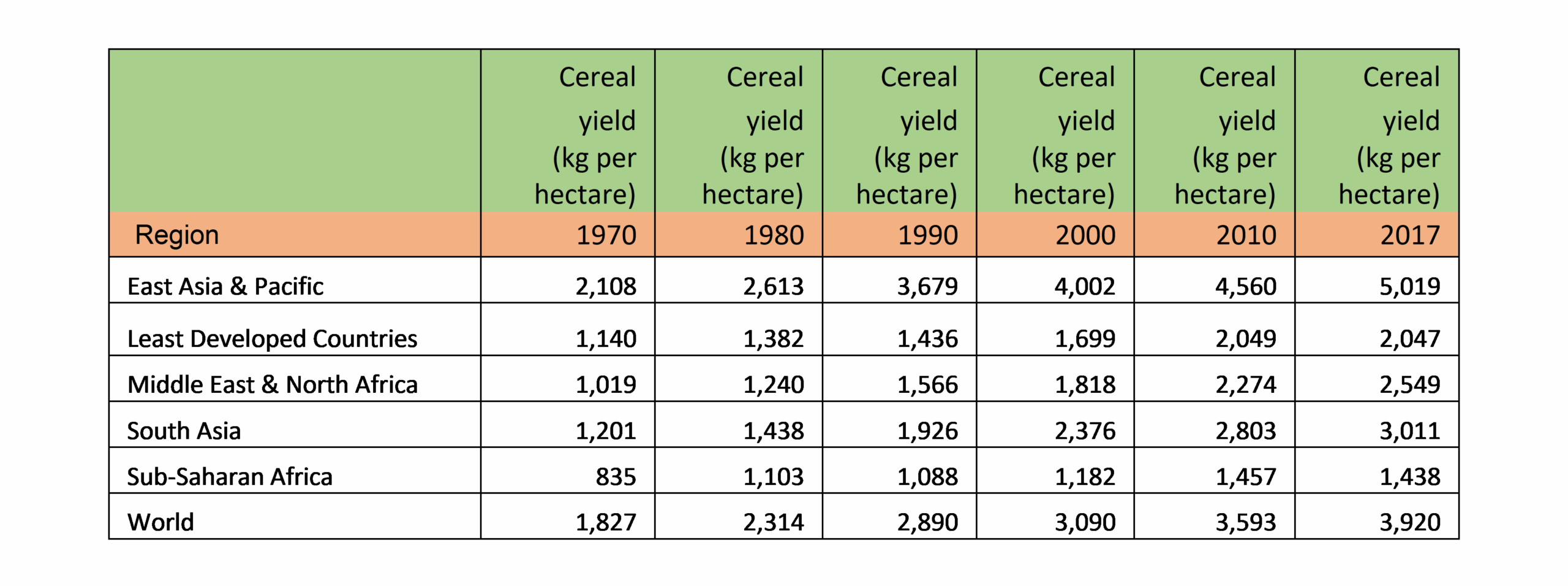

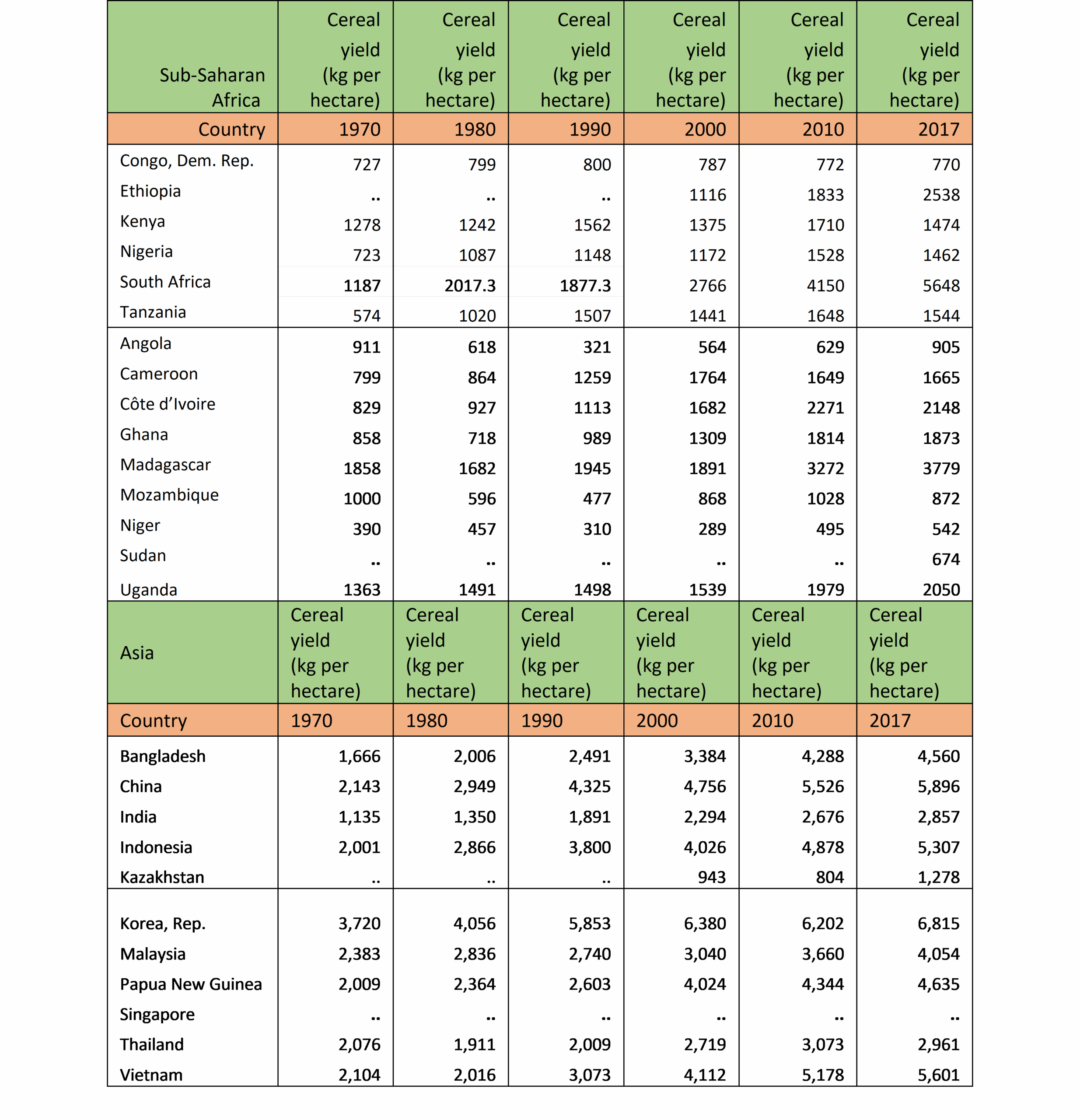

Table 3: Cereal Yield (kg per hectare) by regions in sub-Saharan Africa and other developing regions, 1970-2017

Table 3 gives agricultural outputs in terms of cereal yields (kg per hectare), between 1970 and 2017:

Agricultural output in terms of cereal yields (kg. hectare) in sub-Saharan Africa increased to 1,088 kg per hectare in 1990 from 835 kg in 1970. Between 1990 and 2017, the yield per hectare in sub-Saharan Africa increased to 1,438 kg per hectare in 2017 from 1,088 kg in 1990 (Compared with 3,679 kg per hectare in 1990 from 2,108kg in 1970, in East Asia and the Pacific. From 1990 to 2017, cereal yields kg per hectare in East Asia and the Pacific increased to 5,019 kg per hectare in 2017 from 3, 679 kg in 1990; that in South Asia increased to 3, 011 kg per hectare in 2017 from 1,201 kg per hectare in 1970).

- The yields in Least Developed Countries (33 out of 44 of which are countries in SSA) increased to 2047 kg in 2017 from 1140 kg per hectare in 1970.

- The yield in the world increased to 3920 kg per hectare in 2017 from 1827 kg per hectare of arable land in 1970(see table 3).

Conclusion: The agricultural sector in Sub-Saharan Africa, despite its immense potential with vast arable land and a rich human resource base, has struggled to achieve meaningful outputs since independence in the 1960s. This challenge largely stems from a long-standing lack of attention and commitment from the region’s leadership toward agricultural development. As a result, Sub-Saharan Africa has become the poorest region in the world, where many citizens are caught in a cycle of extreme poverty, hunger, and malnutrition. This neglect weighs heavily on the shoulders of the rural communities, who make up the majority of the population and deserve care and support to thrive.

To further shed lights on the state of agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa in post-independence era, we compare investment levels in agriculture in terms of agriculture machinery (tractors) and yields in selected countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia.

Table 4 gives the number of tractors in selected countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia over the period 1965-2000:

Table 4 gives the number of tractors in selected countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia over the period 1965-2000:

- The number of tractors in Nigeria, with its huge rural population, increased to 11,700 in 1985 from 1,300 tractors in 1965. As of 2000, the number of tractors in Nigeria was 20,006 (compared with an increase to 861,364 tractors in 1985 from 73, 021 in 1965 in China. As of 2000, the number of tractors in China was 989,139 tractors).

- The number of tractors in Ghana declined to 1,956 tractors in 1985 from 2,116 tractors in 1965. The number of tractors in Ghana further declined to 1,936 tractors in 2000 from 1956 tractors in 1985 (compared with an increase to 4,013 tractors in 2000 from 100 tractors in 1965 in Indonesia).

- The combined tractors in seven sub-Saharan African countries with available data in 2000 was 132,489 tractors (compared with 191,631 tractors in South Korea alone, in 2000)

- The number of tractors in India increased to 1,354,864 tractors in 1995 from 48,000 tractors in 1965 (compared with an increase to 224, 909 tractors in 1995 from 197,335 tractors in sub-Saharan Africa in 1965).

- As of 2000, the number of tractors in India was 2,091,000 tractors, that of sub-Saharan Africa remained unchanged over the period 1995 to 2000 at 224, 909 tractors (see table 4).

Table 5 give the number of tractors per sq.km of arable land in selected countries in sub-Saharan Africa and in Asia, over the period 1965-2005:

Table 5 gives the number of tractors per sq.km of arable land in selected countries in sub-Saharan Africa and in Asia, over the period 1965-2005:

- Over the period 1965-1985, the number of agricultural machineries (tractors) per sq.km of arable land in Nigeria increased to 5 tractors in 1985 from 0 tractor per sq.km in 1965, that in Tanzania declined to 9 tractors in 1985 from 28 tractors in 1965, that in Ghana declined to 8 tractors in 1985 from 12 tractors in 1965, that in Madagascar declined to 6 tractors)in 1985 from 9 tractors in 1965,

(Compared with 127 tractors per sq.km of arable land in 1985 from 31 tractors per sq.km in 1965 in Malaysia).

- The combined tractors per sq.km of arable land in five sub-Saharan African countries — Nigeria, Kenya, Tanzania, Ghana, and Madagascar — was 48 tractors per sq.km of arable land in 1985 (compared with 62 tractors per sq.km of arable land in South Korea over the same year, 1985).

- The average number of tractors per sq.km of arable land in South Korea increased to 62 tractors per sq.km in 1985 from 3 in 1975(compared with a stagnant 24 tractors per sq.km in sub-Saharan Africa over 1975-1985). Thus, the average number of tractors per sq.km in sub-Saharan Africa remained stagnant at 24 tractors per sq.km over the period 1975- 2005, that in South Korea increased from 62 tractors in 1985 to 1,387 tractors per sq.km of arable land in 2005(see table 5 and 2).

Table 6 shows agricultural outputs in term of cereal yields (kg per hectare) in selected countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, over the period 1970-2017:

Table 6 shows agricultural outputs in term of cereal yields (kg per hectare) in selected countries in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, over the period 1970-2017:

- Cereal yields (kg per hectare) in Nigeria increased to 1,462 in 2017 from 723 kg per hectare in 1970, that in Tanzania increased to 1,544 kg per hectare in 2017 from 574 kg per hectare in 1970 (compared with 4,580 kg per hectare in 2017 from 1,666 kg in 1970 in Bangladesh).

- Cereal yields (kg per hectare) in Ghana increased to 1,873 kg in 2017 from 858 kg per hectare in 1970, that in Cote d’Ivoire increased to 2,148 kg per hectare in 2017 from 829 kg per hectare in 1970 (compared with 5,307 kg per hectare in 2017 from 2,001 kg in 1970 in Indonesia).

- Cereal yields (kg per hectare) in Kenya increased to 1,474 kg in 2017 from 1,278 kg per hectare in 1970, that in Niger increased to 542 kg per hectare in 2017 from 390 kg per hectare in 1970 (compared with 4,635 kg per hectare in 2017 from 2,009 kg in 1970 in Papua New Guinea).

- Cereal yield kg per hectare in Mozambique declined to 872 kg per hectare in 2017 from 1,000 kg in 1970, that in Congo Democratic Republic increased to 770 kg per hectare in 2017 from 727 kg in 1970 (compared with 5,896 kg per hectare in 2017 from 2,143 kg per hectare in 1970 in China).

- Cereal yield kg per hectare in Angola declined to 905 kg per hectare in 2017 from 911 kg per hectare in 1970, that in Cameroon increased to 1,665 kg per hectare in 2017 from 799 kg per hectare in 1970, that in Uganda increased to 2,050 kg per hectare in 2017 from 1363 kg per hectare 1970 ( compare with 6,815 cereal yield kg per hectare in 2017 from 3, 720 cereal yield kg per hectare in 1970, in Korea , Rep).

- Thus, over the period 1970-2017,the combined agricultural outputs in these selected Sub-Saharan African countries (increased from 3,073 kg per hectare in 1970 to 4,620 kg per hectare in 2017), which was less than that in South Korea alone (which increased from 3,720 kg per hectare in 1970 to 6,815 kg per hectare in 2017).

- The average cereal yield kg per hectare in Sub-Saharan Africa (48 countries) increased to 1,438 kg per hectare in 2017 from 835 kg in 1970 compared with:

6,815 kg per hectare in 2017 from 3,720 kg per hectare in 1970 in South Korea

5, 896 kg per hectare in 2017 from 2, 143 kg per hectare in 1970 in China

5,307 kg per hectare in 2017 from 2,001 kg per hectare in 1970 in Indonesia

4,054 kg per hectare in 2017 from 2,383 kg per hectare in 1970 in Malaysia

4,635 kg per hectare in 2017 from 2,009 in 1970 kg per hectare in Papua New Guinea

4,560 kg per hectare in 2017 from 1,666 kg per hectare in 1970 in Bangladesh

5,601 kg per hectare in 2017 from 2,104 kg per hectare in 1970 in Vietnam (see table 6 and 3).

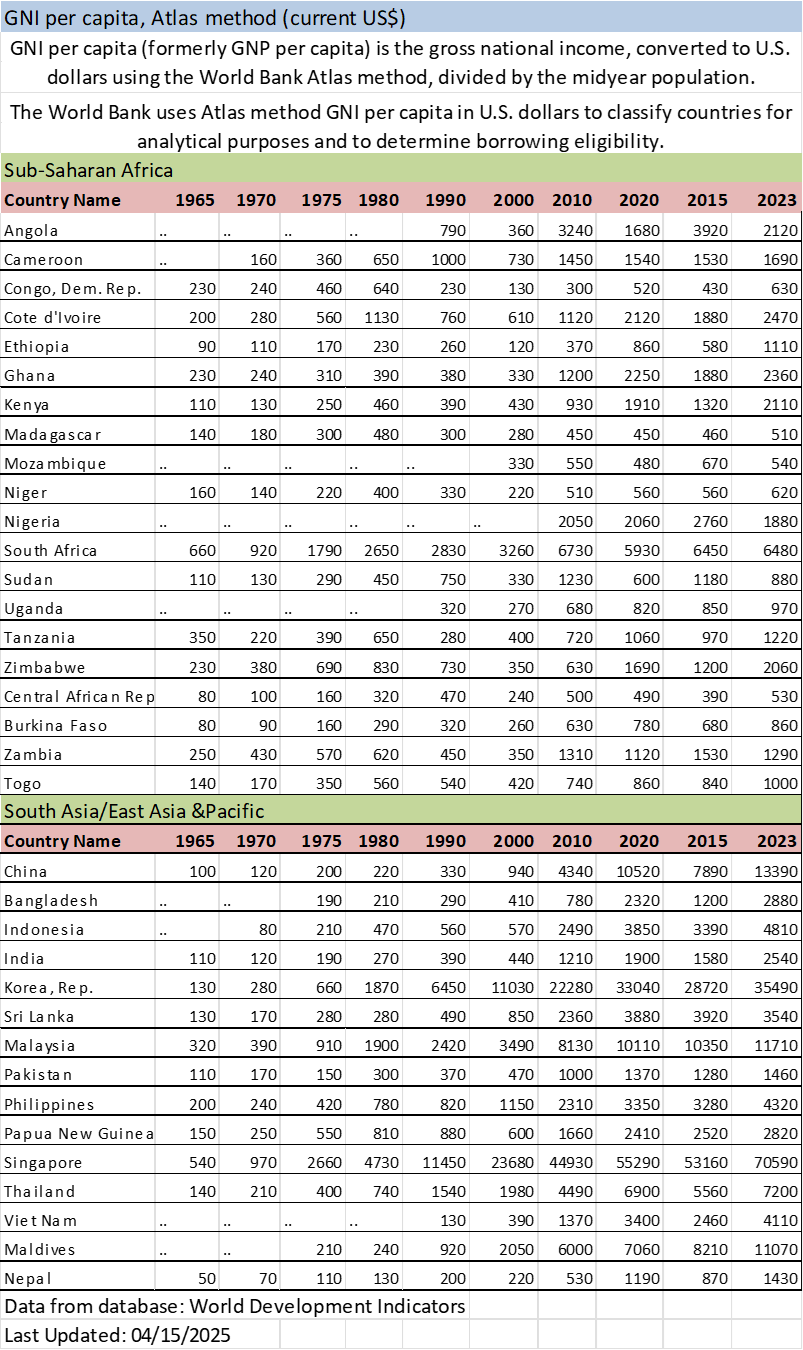

Economy

It has been argued that many Sub-Saharan African countries, which today are among the poorest countries in the world, had per capita incomes that were either higher than or at least equal to those in many countries in East Asia & Pacific in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Since the Sub-Saharan African countries had significant endowments of environmental resources, they were expected to outperform their relatively less endowed Asian counterparts and achieve rapid development in post- independence period (World Bank, 2017). Table 7 gives GNI per capita in selected countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia.

Table 7 gives GNI per capita, Atlas method (current US$) in developing regions over the period 1965 -2022:

In 1965, the Gross National Income per capita in Ghana, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, and Madagascar was notably higher than that of China, India, the Republic of Korea, and Sri Lanka, indicating a promising economic landscape for these African nations at the time ( see table 7 on the left). However, by the year 2023, the stark contrast in economic progress becomes evident, as the Gross National Income per capita for the Republic of Korea and China has experienced remarkable growth, reaching $34490 and $13390, respectively. In sharp contrast, the Gross National Income per capita for the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, and Ghana has shown only modest advancements, climbing to $630, $2470, and $2360, respectively, from 1965 to 2023, highlighting the significant disparities in economic development between these countries and their Asian counterparts over nearly six decades.

The critical question within development economics explores the underlying reasons for the exceptional economic growth seen in East Asian nations like China and South Korea, in stark contrast to many Sub-Saharan African countries that have faced significant challenges in achieving similar levels of sustained growth. The factors driving these differing paths are complex and varied; however, a comprehensive analysis reveals the key elements that shape these outcomes:

Investment in Education and Human Capital

South Korea and China made significant investments in education and health, leading to early achievements in high literacy rates and a skilled workforce. By the 1970s, South Korea’s literacy rate surged from 22 percent in 1945 to over 90 percent. In contrast, many Sub-Saharan African nations continue to face challenges, as their education systems suffer from chronic underfunding, resulting in low completion rates and insufficient technical training.

Effective Governance and Policy Choices

East Asian nations, despite their imperfections, have historically been characterized by robust and centralized governance structures that facilitate long-term strategic planning. In contrast, the post-independence era of Sub-Saharan Africa has been marked by significant challenges, including pervasive political instability, widespread corruption, civil conflicts, and frequent changes of regime, all of which have substantially undermined the potential for sustained investment and economic growth in the region.

Industrialization and Export-Oriented Growth

East Asia has historically centered its economic strategies around manufactured exports, which are characterized by their higher value and relative stability in comparison to other forms of trade. In contrast, many Sub-Saharan African economies have become increasingly reliant on raw commodities such as oil, cocoa, and gold, which are susceptible to significant price fluctuations and contribute minimal value-added processes. This pronounced lack of diversification within Sub-Saharan African economies has resulted in heightened vulnerability to external economic shocks, posing considerable challenges to their sustained growth and development.

Infrastructure Development

East Asian nations have historically prioritized investment in transport, electricity, and digital infrastructure, thereby fostering an environment that is conducive to robust industrial growth. In contrast, Sub-Saharan African countries frequently experience deficiencies in both infrastructure and institutional capacity, which significantly impedes their ability to attract foreign investment and scale their industrial activities.

Political Stability and Institutions

Understanding the Challenges

Unity: Our Collective Long held Aspiration

Even prior to gaining independence, the Pan-African vision of continental unity was

recognized as essential for achieving complete independence, self-reliance, and

sustainable development. In the years leading up to independence in the 1960s, African

leaders, both on the continent and in the Diaspora, began to perceive Africa not as a

collection of fragmented nations but as a unified entity. They initiated discussions about

continental development rather than focusing solely on isolated progress within specific

countries or regions. These perspectives gradually became integrated into the nationalist

movements and found their most explicit expression during the independence struggle. The

Pan-African Congress convened in Manchester in 1945, uniting African nationalist leaders

and those from the Diaspora, outlining Africa’s aspirations which included securing

independence from colonial domination to enable self-governance and fostering

continental unity to facilitate accelerated economic growth and establish a robust presence

in the global arena. This Pan-African ideology gained traction at the sub-regional level as

nationalist movements rallied the support of peasants and workers in their fight against

colonial rule, ultimately realizing their independence with this collective vision as their

guiding principle.

Since gaining independence, the dream of unity in Sub-Saharan Africa has sadly not been

realized, remaining a topic of discussion at summits but never fully achieved. This has led to

ongoing poverty, persistent underdevelopment, frequent conflicts, devastating wars,

widespread hunger and malnutrition, recurrent displacement, and horrific violence against

civilians, alongside rampant corruption and governance issues that have caused untold

suffering for the vast majority of the population. It is perplexing that despite its rich natural

resources and human capital, Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest number of hungry

individuals and the lowest per capita income in the developing world. How can we explain

that a region that once united to secure independence is now plagued by ongoing conflicts

that have resulted in the highest number of refugees and displaced persons globally? How

is it that Sub-Saharan Africa, despite its wealth of resources, hosts the largest concentration

of least developed countries? Furthermore, how can we reconcile the fact that this region,

endowed with vast natural and human resources, also has the highest number of low-

income countries and the largest share of nations with a low human development index?

Lastly, it is incomprehensible that the area recognized as having the world’s largest arable

landmass is home to the greatest number of hungry and malnourished people. Unity is the

only solution to these dilemmas. A “United Sub-Saharan Africa” will be better equipped to

end poverty, underdevelopment, conflicts, and continued dependency on aid, and be able to solve challenges that Sub-Saharan Africa has faced since independence in the 1960s.

In 1980, African Heads of States and Governments, in Monrovia, Liberia, declared

In assessing the economic problems of our continent, we are convinced that Africa’s

underdevelopment is not inevitable. Indeed, it is a paradox when one bears in mind the

immense human and natural resources of the continent. In addition to its reservoir of

human resources, our continent has 97 percent of world reserves of chrome, 85 percent of

world reserves of platinum, 64 percent of world reserves of manganese, 25 percent of the

world reserves of uranium and 13 percent of world reserves of copper, without mentioning

bauxite, nickel and lead, 20 per cent of world hydro-electrical potential, 20 percent of

traded oil in the world if we exclude the United States and the USRR; 70 percent of world’s cocoa production; one-third of world coffee production, 50 percent of palm produce, to mention just a few. The question then becomes: Why do we remain underdeveloped and poor?

According to African Natural Resource Center (ANRC)

Sub-Saharan Africa is home to the world’s largest arable landmass; it is home to the second and longest rivers (the Nile and the Congo); and it is home to the second largest tropical forest. The total value added of its fisheries and aquaculture sector alone is estimated at USD 24 billion; about 30% of all global mineral reserves are found in Africa; Africa’s natural resources

provide a unique opportunity to foster human and economic development. However, weak

institutions, corruption, and governance challenges have been fundamental obstructions.

Sub-Saharan Africa Through a Global Lens

The world sees Sub-Saharan Africa as a region with resources that are inexhaustible; the

world sees Sub-Saharan Africa as a region which the Nature has scattered her bounties

with the most lavish land; the world sees Sub-Saharan Africa as a continent with several

might rivers that are navigable and that afford every facility for commerce and intercourse

with the numerous nations and tribes who inhabit the countries and their vicinity.

Furthermore, the world regards the productive capability of Sub-Saharan African soil as of

infinitely more values, especially those which require industry and skills in their culture.

The world looks at Sub-Saharan African forests, and the plains, and the valleys, and the

rich alluvial deltas which it would take centuries to exhaust of their fertility and products.

The world believes that if we were United, our agricultural production would embrace all

the marketable commodities imported from the world market.

In the world’s eyes Sub-Saharan Africa has unlimited tracts of the most fertile portion of the

earth. The world understands Sub-Saharan African forests and wood as extremely valuable

with various species of timber which grow in vast abundance and are easily obtained. In

the world’s eyes, our region has gums, nuts, copal, palm-nuts, shea nuts, kola nuts, and

cocoa nuts; and all kind of fruits- orange, lemons, citrons, limes, pines, guavas, tamarinds,

paw-paws, plantains, bananas, and mangoes, to mention just few; of grain, there are rice,

Indian corn, or millet, etc. The quantities of all these can be raised to any extent and be

limited only by demand; of natural drugs, there are aloes and cassia, frankincense,

cardamoms and grains of paradise.

Among miscellaneous products which are in great demand in the West, there are ivory,

bees’ wax, caoutchouc and many others. The bees’ wax of our region is in great repute and

can be obtained in any quantity. We, Sub-Saharan Africans, know our region has been

blessed by Nature and by divine Providence, and we know our region possesses all the

resources above and even more. But we have been asking: Why are we powerless to make

these resources available to the noblest purposes?

The most valuable advice one of the travelers gave to Sub-Saharan Africans during

colonization was: “Unity and the advantage of your immense natural resources and the

cultivation of your rich lands are the only way You will ever find out a complete

independence, comfort, and wealth.” And he said: “You may, if You please, if God gives You

health and You become as independence as You wish, comfortable and happy as You

ought to be in this world, the flat lands and other natural resources around You can be key!”

So, Why are we powerless to make these resources available to the noblest purposes?

The answer is Clear: Since the 1960s, sub-Saharan Africa and its citizens have faced

significant challenges that have hindered our progress. We have been constrained by weak

institutions, rampant corruption, governance failures, and a glaring absence of visionary

leadership. For too long, elites and institutions have failed to fulfill the aspirations of the

Sub-Saharan African people. Leadership has been lacking in unity and resolve, neglecting

to dismantle the remnants of colonialism that still impact us today. There has been a

prolonged failure to collaboratively forge a “new rising Sub-Saharan Africa” that honors and

reflects our rich history and values. Moreover, leadership has consistently shied away from

uniting to champion our heritage, values, and dignity on the global stage.

Bleak Prospects for Decades Ahead

According to some global financial institutions, “Most of sub-Saharan African countries

can’t be expected to improve their lot because they lack the basic institutions,

infrastructures, and capital needed to develop. In the meantime, Sub-Saharan African

population continues to grow, and it is estimated to reach 2.5 billion persons by 2050.

Future generations will likely be more numerous, poorer, less educated, and more

desperate.”

The dim outlook for swift economic advancement amid persistent population growth has

been characterized by various global institutions as,

Almost a nightmare…. At the national level the socio-economic conditions would be

characterized by a degradation of the very essence of human dignity…. Poverty

would reach unimaginable dimensions …. The conditions in urban centers would

also worsen…. The level of unemployed searching desperately for the means to

survive would imply increase in crime rates and misery.

The current state of Sub-Saharan Africa stands as a poignant reminder of the challenges

we face, as extreme poverty has tragically surged from 282.2 million in 1990 to an

overwhelming 464.2 million in 2024, amid global prosperity during the past five decades. In

contrast, regions like East Asia and the Pacific have made remarkable strides, decreasing

extreme poverty from 1.04 billion in 1990 to just 17.6 million in 2024, while South Asia has

also seen significant progress, reducing the number of individuals living in extreme poverty

from 570.9 million in 1990 to 148.7 million in 2024. On a global scale, the decline in

extreme poverty is encouraging, falling from 2 billion in 1990 to 693 million in 2024.

However, it is heart-wrenching to note that Sub-Saharan Africa remains the only developing

region where extreme poverty continues to rise since 1990, highlighting the urgent need for

a fundamental change.

According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP): “Sub-Sahara Africa is

not the only poor region of the world, but it is the only one with relatively bleak prospects

for the new millennium, fundamental change is imperative.’”

Elite Betrayal

Since gaining independence in the 1960s, sub-Saharan Africa and its people have

experienced a deeply felt sense of stagnation. Many of us carry feelings of frustration,

desperation, and hopelessness, often perceiving our circumstances as an unavoidable fate

with no clear path forward. Yet, we hold a profound understanding of the wealth and

potential our beloved region possesses. We are clear about our aspirations and the direction

we want to take, and we have a deep awareness of the root causes of our challenges. We recognize the solutions that exist for us and are actively seeking to understand the reasons

behind our current state of inertia and stagnation.

We understand that we have faced significant challenges, including ineffective institutions,

pervasive corruption, governance issues, and a lack of visionary leadership; we recognize

that elites and institutions have struggled to meet the aspirations of Sub-Saharan Africa

and its people; we empathize with the frustration of being stifled by leaders who have not

come together to dismantle the lasting impacts of colonialism; we acknowledge the

limitations imposed by leadership that has not united to create a “new nation” that reflects

our rich history and values; we feel the weight of being obstructed by those who have not

united to champion our heritage, our principles, and our dignity on the global stage.

We, as Sub-Saharan Africans, deeply understand that the Pan African vision of unity

across our region is not just an ideal, but a heartfelt necessity for overcoming our shared

challenges, and we hold onto the belief that it is within our reach. This vision has often been

dismissed as unrealistic due to the painful reality that many of our leaders have prioritized

personal gain over our collective strength, allowing former colonial powers to retain

influence while neglecting to empower a strong Sub-Saharan African Union that could truly

serve the people of sub-Saharan Africa. We acknowledge that our region is richly blessed by

nature and divine providence, positioning us among the wealthiest regions on Earth. Yet we

find ourselves pondering why we struggle to harness our vast resources for the greater good,

and the answer is becoming increasingly evident.

Sub-Saharan Africans Must Now Do the Unthinkable

The challenges facing Sub-Saharan Africa demand more than the vague hopes of

Agenda 2063 or the empty promises of past declarations; they call for a resolute unity among

us all. We must come together, recognizing the extraordinary power of our collective efforts

and a renewed commitment to patriotism and citizenship. It is essential that we establish a

genuine Union government that authentically embodies the will of the people, fostering hope

and driving progress for everyone. This is our moment to rally behind a visionary leader who

can guide us toward the realization of a United Sub-Saharan Africa, a dream rich in justice

and the promise of a brighter future for every member of our community.

At WeUniteSSA, we firmly believe that in times of societal challenges, it is imperative

for citizens to stand up and question the status quo in order to restore integrity and justice.

We recognize that making true sacrifices for the less fortunate and for noble causes requires

unwavering conviction in the righteousness of our mission and the greatness of our vision.

We champion a referendum that calls for unity and the establishment of a strong Union

government that embodies the principles of being of the people, by the people, and for the

people, as the sole path forward to address the pressing lingering issues that sub-Saharan

Africa and its people have faced for too long. This collective dream, long nurtured within us,

is not only urgent but also vital and undeniable, representing the hope for a brighter future

that we all deserve.

But a strong Union government in sub-Saharan Africa will not emerge by mere chance; it

requires the steadfast dedication of the people of sub-Saharan Africa and their global allies

to realize this vision. To reach this objective, we must foster a more vibrant and resilient

understanding of Faith that motivates patriotic Sub-Saharan Africans and their supporters

worldwide to fully embrace the values of the common good and humanity. The people of

sub-Saharan Africa have endured far too much. It’s time for a fundamental change.

WeUniteSSA is thrilled to announce the launch of WeUnite Action for Sub-Saharan

Africa, an impactful initiative that captures the collective aspirations of the people and

pursues a noble mission. By collaborating with regional governments, we will advocate for

the essential role of referendums and set forth clear guidelines for their execution. We will

activate nearly 200 dedicated Sentinel activists and 500 grassroots activists across every

nation in Sub-Saharan Africa, empowering them to educate citizens on the referendum

process, their fundamental rights, and the significant advantages of unity. Through WeUnite

Action for Sub-Saharan Africa, we remain resolute in our commitment to amplify the voices

of citizens throughout the region, ensuring that leaders in Sub-Saharan Africa are intimately

connected to the hopes and challenges faced by the communities they serve.

As Benjamin Franklin once said: “A Nation of well-informed men who have been taught to know and prize the rights which God has given them cannot be enslaved. It is in the region of ignorance that tyranny begins,” he said. James Adams well put it in

these terms: “No people will tamely surrender their liberties, nor can any be easily subdued, when knowledge is diffused and virtue is preserved,” he said.

WeUniteSSA’s mission transcends the simple act of changing the conversation; we

are dedicated to reshaping the very essence of Sub-Saharan Africa. With unwavering

passion, we strive to amplify the voices of citizens throughout the region, creating a profound

connection between the leaders of Sub-Saharan Africa and the aspirations and challenges

faced by the communities they represent.

Join us in this vital mission. Your participation in this vital mission is essential. Your generous contributions create a powerful ripple effect within our organization, empowering us to sustain our crucial initiatives and propel our mission with renewed vigor and

commitment. Each donation fuels education efforts, outreach programs, and the logistical support needed to realize this referendum. By giving today, you are helping to forge a future where Sub-Saharan Africa thrives, united and self-governing. Every dollar you invest brings us closer to a reality where our voices resonate, our decisions matter, and the future of Sub-Saharan Africa is truly in the hands of the people, breaking free from the dominance of a select few and outdated conventions and norms.